|

A LIVE LANGUAGE: Chaldeans who speak, learn

Aramaic say it helps preserve their culture

BY ALEXA CAPELOTO

FREE PRESS STAFF WRITER

Mel Gibson's controversial film "The Passion of the Christ" has been

strapped with several labels in recent weeks: brutal, beautiful, horrific,

haunting, anti-Semitic, true, untrue.

But whatever it is, members of the local Chaldean community insist, it is

not a dead-language film.

"The Passion" is shot entirely in Aramaic and Latin with English

subtitles.

Although the languages -- one believed used by Jesus; the other the tongue

of Imperial Rome -- are commonly considered lost relics of another era,

modern variations of Aramaic persist in small pockets around the world,

including the Chaldean enclave of metro Detroit.

"Our community is extremely excited about the film," said Martin Manna,

31, a Chaldean business leader from Bloomfield Hills. "But the reaction

from our community is, 'Why is everyone seeing this as a dead language?' "

Local Chaldeans, Catholics from Iraq, said they are thrilled to see their

language spotlighted in a big-budget movie. Some are determined to use the

wave of publicity to push for preservation of their fading tongue.

"We have to keep our heritage," said Suad Gorial, who teaches a modern

dialect of Aramaic at St. Joseph Chaldean Catholic Church in Troy. "If we

have no language, we have no history."

Chaldeans have long guarded Aramaic as their own oral tradition. Many have

absorbed Arabic in Iraq or English in the United States to get by, but

Aramaic is the language of their Bible, their prayers and their native

villages.

Wednesday morning, about 40 women in lace veils and dark coats filed into

St. Joseph for their daily prayers. An older woman with gray hair gathered

at her nape called out in quick, measured Aramaic, and the group responded

in unison.

The voices swirled back and forth in the gilded sanctuary for nearly an

hour as the women prayed. Men trickled in to join them in time for the

daily 11 a.m. mass.

Some of them can't read or write the language they have spoken all their

lives, so they go to Gorial's class Tuesday nights to work with the

22-letter alphabet. After a few curves, slashed lines and dots, this

week's students knew how to write and pronounce six consonants and two

vowel marks.

They didn't get these lessons in Iraq, a Muslim country where education is

in Arabic, not the Aramaic of its Christian minority.

"It's important for me to learn. This is my language," Intesar Nalow, 62,

said after class.

In her native city of Baghdad she and others knew "nothing about the

language," she said. "It's not open. Here, more open."

Gorial, Nalow and others said they plan to see "The Passion," not only for

its religious significance but for the challenge of deciphering the

ancient form of Aramaic depicted on screen.

Manna, who is president of the Chaldean American Chamber of Commerce in

Farmington Hills, saw a matinee Wednesday and left the theater moved by

the story but slightly confused by the language.

"These people were obviously amateurs when it came to the language," Manna

said of the actors. "We did catch about 30 to 40 percent of it."

Gibson chose Aramaic because it was the common language of the era and

region of Jesus. Jesus' last words on the cross, according to the New

Testament, were Aramaic for "My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?"

Since then, Aramaic has evolved and splintered into dozens of dialects.

Jews once spoke a western dialect, while Chaldeans and Assyrians used an

eastern dialect. Chaldeans today speak a modern form they call Chaldean,

though scholars and linguists call it Syriac.

"There are many, many forms; some of them I really can't even read," said

Charles Krahmalkov, a recently retired professor of ancient and biblical

languagesat the University of Michigan. "Dictionaries are coming out now

all the time on the various Jewish dialects and Christian dialects."

Krahmalkov said he was astonished when he learned Gibson was filming in

Aramaic and Latin.

"I don't think it was the first time it was done, but it is usually done

in English and spiced with foreign languages," he said. Gibson "had a

conception and an idea, and it was a fascinating one."

Aramaic became the lingua franca of the Near East around 900 B.C., when

civilizations were looking for an international language for education and

trade. It remained strong until the 7th-Century Arab conquest.

Today, the goal of older Chaldean Americans is to teach the language to

their children who have grown up speaking English.

One group, Chaldean Americans Reaching and Encouraging of West Bloomfield,

is working on a regional curriculum for modern Aramaic to be taught in

churches.

"It's such a beautiful language and it's so old and carries so much," said

Bashar Hannosh, 32, president of CARE. "We feel if we don't preserve it,

we're going to lose it."

The Rev. Emanuel Shaleta, pastor of St. Joseph, said he takes pride in

speaking a variation of the language spoken by Jesus. And he marvels that

Aramaic lives on after such a long history.

"You can say it is a miracle," he said.

* * *

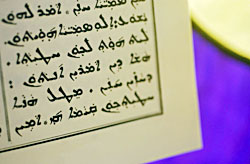

ERIC SEALS/DFPPart of Luke's gospel, as written in Aramaic, believed to be

the tongue of Jesus.

* * *

A FEW COMMON PHRASES TRANSLATED

I love you (said to a woman). -- K-haibinnakh.

What's for dinner? -- Ma ittan ta ashaya?

I live in the Motor City (said by a man) -- Ana k-aishin mdhyta d-sayarat.

Where's the bathroom? -- Aika iyle betha d-maya?

Do you come here often? (said to a woman) -- Kul gaha k-athyat akha?

Happy Birthday (said to a woman)! -- Brykha aidha d-hwaithakh!

Source: Suad Gorial, who teaches a modern Aramaic dialect at St. Joseph

Chaldean Catholic Church in Troy

http://www.freep.com/entertainment/movies/aram26_20040226.htm |