|

Dossier:

Samir Geagea

Leader of the Lebanese Forces (LF) movement

by

Ziad K. Abdelnour

Lebanon's most prominent political prisoner has

spent the last decade of his life in solitary confinement, three stories

beneath the Ministry of Defense in a small, windowless cell. Unlike Nelson

Mandela during his 27 years in prison, he is not permitted to send or

receive mail. He is not allowed to read books or periodicals containing

political information about Lebanon, and cannot watch television or listen

to the radio. He is handcuffed and blindfolded whenever he is taken out of

his cell for exercise or brief visits by relatives and lawyers under the

watchful eye of monitors. His guards are forbidden to converse with him

beyond simple commands.

The conditions of Samir Geagea's imprisonment speak

volumes about his stature as a nationalist leader. The main concern of

Lebanon's Syrian-backed government is not that the former commander of the

Christian community's largest wartime militia will find a way to escape

through tons of reinforced concrete and steel or evade the heavy

concentration of Lebanese and Syrian soldiers at the ministry, but that he

will find a way to communicate with his followers. Geagea's words

are regarded by Syria as an existential threat to its continuing

occupation of Lebanon.

Background

Geagea was born in 1952 in the Ain Roumaneh neighborhood

of Beirut to a family of modest means from the northern Lebanese village

of Bsharri. The son of an adjutant in the Army, Geagea came of age at a

time when the barriers to socio-economic advancement within the Christian

community had begun to weaken and record numbers of students were arriving

at universities on the strength of their intelligence and self-discipline,

rather than wealth or family connections. Geagea was one of them, arriving

at American University of Beirut (AUB) to study medicine in 1972.

AUB, the birthplace of political movements ranging from

the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) to the Popular Front for the

Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), was a hotbed of activism in the early

1970s. Although Geagea had been active in the student branch of the

Kata'ib (Phalange) party when he was in high school, it was here that he

found his leadership calling.

After the outbreak of civil war in 1975, Geagea

interrupted his studies to participate in the defense of Christian towns

and villages from Palestinian attack. Although he would later complete his

studies at the University of St. Joseph, Geagea never practiced medicine -

the massacres and dislocations experienced by the Christian community in

the early war years led him to commit his life to the defense of his

homeland and people. As the Lebanese Army splintered and government

authority crumbled, Geagea proved himself to be a fearless soldier and

able leader, quickly rising through the ranks of Bashir Gemayel's Kata'ib

militia and its successor, the Lebanese Forces (LF).

The Palestinian threat to Lebanon had been counteracted to

a certain extent by the end of 1976, but the Christian community faced an

even more powerful threat with the entry of Syrian forces into Lebanon

that year. While the Kata'ib staunchly opposed Syrian intervention, some

Christian leaders who had steadfastly fought (or sent their followers to

fight) the PLO's attempted takeover of the country were perfectly willing

to accommodate Syria's hegemonic ambitions so long as they obtained a

share of the post-war political spoils. Former President Suleiman Franjieh,

whose militiamen fought bravely against Palestinians with whom he had no

financial interests, defected from the Christian alliance because of his

long-standing business ties to Syrian President Hafez Assad. By 1978,

Franjieh's Zghorta-based militia, commanded by his son, Tony, was

coordinating directly with Syrian military intelligence and waging a

relentless wave of terrorism, ambushes, and assassinat! ions against the

Kata'ib throughout north Lebanon. When a local Kata'ib leader, Joud

al-Bayeh, was murdered by a Franjieh assassination squad on June 8,

Gemayel tried to settle the problem through negotiations via Maronite

Patriarch Antonios Khreich. When these negotiations failed, Gemayel

decided to retaliate with a reprisal raid deep into the warlord's domain

and hand-picked a special force to carry it out. One of the units was led

by 26-year old Geagea, whose hometown was traditionally at odds with the

Frangieh clan

The plan was to arrest Joud al-Bayeh's assassins, who were

seeking protection and refuge in Franjieh's palatial summer residence in

Ehden, a symbol of the family's prestige and a major arsenal and

communications center. On the evening of June 12, Geagea's task force

infiltrated the area at night and began attacking the compound just before

dawn. The defenders refused to surrender and a long gun battle ensued in

which Geagea was seriously injured and fell unconscious on the road

leading to the compound. The operation involved close house to house

combat and was successful from a military standpoint, but when the smoke

cleared and Gemayel's men entered the compound, they unexpectedly

discovered among the dead Tony Franjieh and several members of his family

in one of the guards' hangars (the warlord's unwillingness to surrender in

spite of the imminent danger to his family has remained an enduring

mystery).

After recuperating at a hospital in France, Geagea

returned to Lebanon and was appointed commander of LF forces in north

Lebanon. Over the next several years, he fortified LF outposts, expanded

recruitment and built new training centers. More importantly, he earned

the unswerving loyalty of roughly 1,500 militiamen under his direct

command. Most, like Geagea, had been dislocated from their villages and

towns in areas of north Lebanon controlled by Syria and its militia allies

- they lived in barracks, unlike LF soldiers in east Beirut, who could

return to their homes each night. Having tasted insecurity so acutely,

Geagea and his followers viewed the security of the Christian community,

not its political share of the post-war spoils, as their top priority.

Lebanon's First Republic had failed to provide this

security. The LF's main function was to fill the security void left by the

breakdown of the army and government administration - a mandate that also

necessitated the development of a highly organized civil infrastructure.

Unlike their counterparts in Syrian-occupied Lebanon, inhabitants of the

LF-ruled enclave enjoyed modern healthcare, affordable public transport,

welfare support, and personal security. What little prosperity the

Lebanese Christian community still enjoys today is largely due to the LF's

success in preserving an environment in which children could still go to

school - in sharp contrast to West Beirut, where the rule of Muslim

militias placed guns, not books, in children's hands.[1]

|

Bashir Gemayel's election as president following the Israeli invasion

of Lebanon in 1982 briefly revived public hopes that the First Republic

could be fixed. These hopes were shattered after Bashir's assassination

and the ascension of his brother,

Amine, who invited American and European peacekeepers to the

capital to support his government. Geagea and other LF leaders staunchly

backed President Gemayel so long as remained committed to the withdrawal

of Syrian forces, but the withdrawal of American and European peacekeeping

troops in February 1984 led the president to seek rapprochement with

Damascus. Moreover, Gemayel attempted to strengthen his bargaining hand in

negotiations with Syria by asserting control over the LF. In Novem! ber,

the president succeeded in securing the replacement of LF chief Fadi Frem

with his nephew, Fouad Abi Nader. However, a faction of the LF headed by

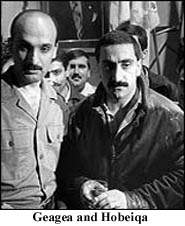

Geagea and LF intelligence chief

Elie Hobeiqa sidelined Abu Nader and took control over the

Christian enclave in March 1985.

Hobeiqa soon made an astonishing political turnabout of

his own, aligning himself with Damascus in hopes of reaching an accord

with Syrian-backed militias and assuming the presidency in a Syrianized

post-war republic. In spite of widespread Christian opposition, Hobeiqa

signed the December 1985 Tripartite Accord, a Syrian-brokered agreement

that would have legalized the Syrian presence in Lebanon. In response, LF

forces loyal to Geagea swiftly took control over the Christian enclave and

Hobeiqa fled to Syrian-occupied territory, nursing an intense personal

hatred of Geagea.

Geagea's ability to mobilize the LF rank and file twice

against those who sought to accommodate Syria's hegemonic ambitions had

much to do with his incorruptibility. Unlike other "warlords" in Lebanon,

Geagea had "an almost puritanical disdain for material concern," notes

historian Theodor Hanf in his voluminous study of the war.[2]

Even Washington Post correspondent Jonathan C. Randal, who is

scathingly critical of Maronite militia leaders in his best-selling book

on the war, described Geagea as "well-read, thoughtful, and possessed of a

revolutionary soul."[3]

At the time, Geagea's defiance of Damascus appeared risky.

By the mid-1980s, the LF had lost its principal external patron (Israel),

the Christian community's financial strength had been devastated by the

collapse of the Lebanese economy, American interest in supporting Lebanon

had dropped to nil, and Syrian forces or their militia allies had gained

control of most of the country. However, Geagea managed to defend the

Christian enclave by forging an alliance with Iraq and maintaining close

relations with the United States. The logic of the Iraq alliance was pure

and simple - Saddam Hussein had no interests in Lebanon other than to

check Syrian expansion. Iraqi arms enabled the LF to build the Christian

enclave into an impenetrable fortress. As Lebanon's Muslim militias turned

on each other with a ferocity not seen in Lebanon since the height of the

war in 1976, residents of the Christian enclave went about with their

lives as best they could.

The Inter-Christian War

Unfortunately, the hard-won security enjoyed by the

Christian community came undone. In the fall of 1988, a constitutional

crisis unfolded because of the parliament's inability to agree on a

presidential successor to Gemayel. Fifteen minutes before the expiration

of his term, Gemayel appointed the commander of the Army, Gen.

Michel Aoun, interim prime minister until such time as a new

president could be elected. Although Aoun had thousands of well-trained

and equipped soldiers at his command, he exercised little authority

outside of the presidential palace and a small area of east Beirut.

Following an Arab League meeting in Fas and encouragement from the Syrians

to extend his authority to the Christian enclave, in early 1989 General

Aoun demanded that the LF withdraw from a number of strategic areas,

including the capital's main port.

Geagea opposed Aoun's drive to expand his authority and

power at the expense of the LF for several reasons. First, so long as

other militias in the Syrian occupied areas continued to be armed and

trained by Damascus and Tehran, the LF militia served many critical

functions in the defense of the Christian homeland that could not readily

be assumed by the army. A militia, by nature, is premised on the idea that

locally organized units, fighting in defense of their own villages,

outperform army regulars who are away from home. It was this principle

that allowed Lebanese Christians to defend themselves against overwhelming

odds during the war - weakening the militia would leave the community

exposed.

Moreover, while all the other militias were operating to

defend their own constituents, political considerations prohibited the

army from acting as defender of the Christian community. The Army follows

whichever command it receives - had Aoun been replaced, the same army

could have been used to achieve diametrically opposing goals as an

instrument of Syrian occupation. Even with Aoun at the helm, Geagea feared

the general's ambition to lead all of Lebanon could bring him either to

cut a deal with the Syrians or sacrifice the defense of the Christian

community in pursuit of it - Christian leaders aspiring to public office

had been committing both sins for over a generation. In short, Geagea

insisted that the militia could not be disbanded until a political

settlement dissolving all militias had been reached - until then, homeland

defense came first.

The ensuing violence between the army and the LF,

initiated by Aoun, fatally undermined the Christian community's ability to

defend itself. Dissapointed by Syria's lukewarm response, Aoun declared a

"war of liberation" against Syrian forces in Lebanon. The LF supported him

and put all its potential into this war, but the situation came to a

standstill and the Syrians relentlessly shelled east Beirut, virtually

emptying it of its inhabitants. Areas of the Christian enclave that had

been untouched by violence throughout the entire civil were devastated by

the fighting. After a fierce battle in Souk El Gharb, a ceasefire was

reached and Aoun endorsed a Saudi and American sponsored national

reconciliation initiative.

The Taef Accord

In October 1989, surviving members of Lebanon's 1972-1976

parliament met in Taef, Saudi Arabia, and signed a National Reconciliation

Accord. The agreement provided for political reforms that shifted the

sectarian balance of power in government; the disarmament of all illegal

militias; the redeployment of Syrian forces to the Beqaa Valley within two

years, and the withdrawal of all Syrian forces at a future date agreed

upon by both governments. Aoun ultimately opposed the Taef Accord, arguing

that it effectively legalized the occupation indefinitely. However, Geagea

and Maronite Patriarch

Nasrallah Boutros Sfeir both supported

the agreement because they believed it would put an end to the war, and

because they believed American and Saudi assurances that Syria would

withdraw all its forces once civil peace was restored (although the Taef

Accord did not explicitly require Syria to wi! thdraw, Assad was said to

have privately assured Riyadh and Washington that he would do so).

After a long period of polarisation and fighting within

the Christian enclave, and after the assassination of President-elect Rene

Mouawwad in the Syrian-controlled area of West Beirut, the Syrians invaded

Aoun's area in October 1990. LF units went on high alert to defend their

territory in the event that Syrian troops invaded the Christian heartland

(which they did not, owing to American pressure) and offered protection to

both soldiers and refugees fleeing the fighting. However, Geagea's trust

in the Americans was ill placed.

The Second Republic

From its very beginnings, the new republic was dominated

by pro-Syrian militia leaders, such as

Nabih Berri, who assumed to the post of parliament speaker;

Druze leader

Walid Jumblatt, who (ironically) became

minister of the displaced, and Hobeiqa, who held a number of different

cabinet positions. In light of Syria's refusal to fulfill its obligation

under the Taef Accord and redeploy its military forces to the Beqaa and

its attempts to dominate the political process, Geagea twice declined

cabinet positions offered to him.

Nevertheless, Geagea saw to it that the LF fulfilled its

obligations under the accord by completely dismantling its military

apparatus and reorganizing itself as a political party. In spite of

Syria's blatant violations of the Taef Accord, Geagea rejected calls by

some within the LF to take up arms once again, arguing that the

international community's apathy toward the Syrian occupation would doom

any attempt at armed struggle just as surely as it had doomed Aoun's

misadventure. However, Geagea resolved to resist Syria's renewed campaign

to subjugate Lebanon with all peaceful means at his disposal. The LF

refused to participate in the 1992 parliamentary elections, arguing that

Syria's heavy military presence in the country precluded a free and fair

electoral process.

Geagea's defiance was not powerful enough to bring down

the system, but it was powerful enough to shame the governing elite in the

eyes of the population. Assad tolerated this for a time, while Syria

consolidated its control over the institutions of government. Some

outspoken activists, such as Butrous Khawand, a member of the Kata'ib

Party's politburo and a former LF officer who was active in mobilizing

anti-Syrian protests, were simply

abducted by Syrian military intelligence, never to be seen

again. Because of Geagea's public profile (and highly-skilled bodyguards),

however, Assad could not simply make him disappear. The silencing of

Geagea had to wait until Syria had gained control over the judiciary.

While Lebanon's largely Western-trained judiciary had a

long-standing reputation for integrity, it gradually succumbed to Syrian

domination in the early 1990s. Incorruptible judges were forced into

retirement, while those who were willing to dip their hands into the

cookie jar were promoted and became forever subject to extortion by the

pro-Syrian political class. When the head of the Judicial Inspection

Bureau, Abd al-Basit Ghandour, brought disciplinary charges against two

judges linked to Syrian drug trafficking, Syrian troops surrounded his

home. Not surprisingly, the bureau exonerated the two judges in a sharply

divided vote. Ghandour retired the following year and Munif Uwaydat, a

judge who defended his two corrupt colleagues during the hearing, was

subsequently appointed prosecutor-general.[4]

By 1994, Assad was in a position to bring the full force of! the Lebanese

state down on whomever he liked.

The Crackdown

On February 27, 1994, a bomb exploded in the Sayyidat

al-Najjat church in the village of Zouk Mikael, deep within the Maronite

heartland, killing nine people and wounding dozens. The bombing, which

followed a string of smaller attacks targeting Christians, caused panic

throughout the Christian community. Afterwards, Geagea accused the

government of failing in its primary responsibility of protecting its

citizens. "It is no more acceptable that our officials are content [with

only] voicing condemnation,'' he told reporters.[5]

The explosion was preceded by warnings of church bombings

relayed to the Patriarch by

Hezbollah intelligence operatives and came a few days after the

killing of 43 Palestinians in a Hebron mosque, leading to public

speculation that it was carried out by Muslims. However, government

officials immediately focused their investigation on so-called "Israeli

collaborators" in the Christian community. Several LF members who were

arrested and tortured in the following weeks were said in media reports to

have implicated Fouad Malek, Geagea's second-in-command, who was himself

arrested. On March 23, the Lebanese cabinet issued a decree dissolving the

Lebanese Forces, suspending the news bulletins of private media outlets,

and lifting the postwar amnesty law's protection of those "who continue to

commit" state security crimes.[6]

The government's strategy had become crystal clear - allegations of LF

involvement in the blast were designed to pave the way for Geagea's arrest

for alleged wartime activities.

Geagea, who went into seclusion following the bombing, was

warned by President Elias Hrawi and other sympathetic Lebanese officials

that he was going to be arrested and was offered safe passage out of the

country. But Geagea decided to stay and fight, and was arrested on April

21.

Syria's move against Geagea was clearly inspired by the

regional climate - it came six months after the Oslo Accords were signed,

at a time when the United States was willing to do anything to persuade

Assad to come on board the peace train. American Ambassador Mark Hambley

initially showed interest in the Geagea case but quickly stopped

mentioning it in public.[7]

Lebanese officials were remarkably candid about the political motivation

behind the government's crackdown. "We enacted the amnesty law so that

everyone could join the state-building project . . . unfortunately, [Geagea]

turned down our offers and persisted in his own project," President Hrawi

remarked just weeks after his arrest.[8]

As expected, the authorities used Geagea's arrest as a

pretext to open investigations into his alleged links to several

assassinations and assassination attempts during the war. It turned out

that the government had no substantial evidence of Geagea's involvement in

the church bombing (of which he was eventually found innocent), so his

trial for that crime was repeatedly adjourned for lengthy periods of time

for no explicable reason other than to allow the other "trials" to

proceed.

Although Geagea was represented by a top-notch defense

team led by Edmond Naim, one of the country's leading constitutional

lawyers, all of his trials before the five-member Judicial Council were

gross miscarriages of justice. Detainees who were unwilling to implicate

Geagea were subjected to brutal torture and forced to signed confessions,

a practice documented by Amnesty International and other human rights

groups.[9]

One detainee, Fawzi al-Racy, died in custody - the government labeled his

cause of death a "heart attack," but refused to permit an independent

autopsy or allow his family to see the body, which was rumored to have

been grossly disfigured. That the five-judge panel categorically refused

to disallow confessions extracted through torture came as a surprise to no

one - it had been handpicked to ensure that Geagea was convicted. Moeen

Osseiran, th! e head of Lebanon's Third Appeal Chamber, declined an offer

to serve on the court, claiming his workload was too heavy, but years

later he told friends that the case was too political for him to render a

fair verdict.[10]

Judge George Rizk, an investigating magistrate, recused himself when the

government asked him to indict Geagea.

Lack of supporting evidence and bizarre inconsistencies in

the prosecution claims also went conspicuously unacknowledged by the

judges. At the time of the church bombing, for example, several of the

defendants charged in absentia with perpetrating it were living abroad -

specifically in Cyprus, Canada, Sweden and Australia. According to exit

and reentry records of all four countries, the defendants could not have

been in Lebanon during the period in question. Government prosecutors

claimed that they used fake passports to travel to and from Lebanon but

produced no evidence of this and the claim went unchallenged by the judges.[11]

Interestingly, the Lebanese authorities did not even bother to formally

seek extradition of Geagea's supposed accomplices who lived abroad -

merely the unsubstantiated claim of their involvement provided

sufficient cover fo! r the judges to declare Geagea guilty of ordering the

1990 assassination of Dany Chamoun, the 1989 killing of LF official Elias

Zayek, the 1991 attempted assassination of then-Defense Minister

Michel Murr, and the 1987 killing of then-Prime Minister Rashid

Karami. Geagea received four death sentences, each commuted to life in

prison with hard labor.

Although Lebanese law does not permit appeals of the

Judicial Court's rulings, one of Geagea's trials did receive a judicial

review. One of Geagea's codefendants in the Chamoun murder trial who was

convicted in absentia, Attef al-Habr, later applied for political

asylum in Australia and was turned down. In reviewing Habr's appeal of the

decision in 1999, an Australian federal court closely examined the

proceedings of its Lebanese counterpart and had this to say: "No

Australian Court would ever have convicted the applicant on the basis of

the evidence which appears, from the verdict, to have been put before the

Lebanese Court."[12]

This assessment calls into question the same court's verdicts

against Geagea.

The gross miscarriage of justice inflicted by the Syrians

on Geagea was viewed as deeply unsettling even by many of his enemies who

believe he was guilty of some or all of the crimes for which he was tried.

All major militias carried out assassinations during the Lebanese civil

war - Geagea himself survived nearly a dozen of them. The pro-Syrian daily

Al-Safir remarked after the first of his convictions that "the

Lebanese would have preferred a broader judgment, one against the whole

war rather than the conviction of one of its heroes."[13]

In November 2002, the outgoing president of the Judicial

Council, Nasri Lahoud (who received this appointment because he is related

to the President

Emile Lahoud) complained in an interview

that judicial independence in Lebanon was "mere poetry." Lahoud, who also

spearheaded the government campaign against the LF while serving as Chief

Military Prosecutor, said that the courts functioned as an

"administrative" branch of government.[14].

The Politics of Decapitation

In the years that followed Geagea's imprisonment, LF

members were subjected to intense harassment by the government. Hundreds

were detained and an estimated 1,500 fled the country, while the ban on

the movement limited the ability of those who remained to organize

collectively. At the same time, many Lebanese found inspiration in

Geagea's sacrifice - his imprisonment led many intellectual, students and

professionals to join the LF in spite of the government's intimidation and

harrasment. Geagea's closest supporters in Lebanon, led by his wife

Setrida, remained at the core of serious opposition to the regime.

In recent years, the Syrians tried to paralyze the

movement by encouraging a group of former LF officials to sideline Setrida

and organize independently under their own pro-Syrian political platform

(an initiative that paralleled the hostile takeover of the Kata'ib party

by

Karim Pakradouni). The splitters, led by

Fouad Malek, met publicly with President Lahoud in 2001 and

were reportedly promised a political party license in the name of the LF (which

would allow them to claim an estimated $70 million in LF assets seized by

the government in 1994). Malek called for a general assembly of LF members

to choose a new leadership, but Setrida rejected the obvious ploy to seize

control of the movement. In June, Geagea's lawyers relayed a statement

from their imprisoned client to the media, accusing Malek o! f launching a

"political coup d'etat" aimed at dividing the movement.

|

In an astonishingly blatent display of coordination with the

authorities, Malek issued a rebuttal questioning the authenticity of

Geagea's statement, while Lebanese Prosecutor-General

Adnan Addoum issued a decree prohibiting the LF leader's

attorneys from visiting him in jail (the decree was revoked after protests

by the Beirut Bar Association). Malek quickly lost what little public

support he had in August by publicly supporting the government's arrest of

some 40 pro-Geagea LF activists, including Geagea's political advisor,

Toufic Hindi. Malek subsequently convened a number of public meetings and

conferences, but they were poorly attended and he has yet to receive the

party license promised to him.

Having failed to co-opt Geagea's mass following, the

authorities intensified their crackdown on the LF. Hindi was forced to

read a televised confession admitting to collaboration with Israel and

served 15 months in prison. In May 2002, a prominent member of the LF

student committee, Ramzi Irani, was abducted in broad daylight and

tortured to death, his body eventually found inside the trunk of his car.

As is always the case when anti-Syrian activists are murdered in

Syrian-occupied Lebanon, the criminal investigation went nowhere. Earlier

this month, the corpse of another LF activist, Pierre Boulos, was found in

the trunk of his car. Syria has made no attempt to disguise its killings

of Geagea's supporters as random acts of violence - it wants to make sure

the pattern of assassinations is blatantly self-evident to anyone who

thinks of organizing grassroots opposition to the occupation.

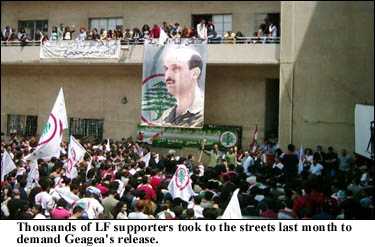

However, Geagea's activists have responded to this

intimidation campaign by intensifying their cries for justice. In

commemoration of the tenth anniversary of his imprisonment, LF activists

in Lebanon and the Diaspora staged several mass demonstrations and

organized petitions calling for Geagea's release that garnered nearly

160,000 signatures. The LF remains today the fastest growing political

institution amongst the Christian students and professionals of Lebanon.

|

As a result of this grassroots effort, traditional Christian political

and religious leaders have become much more vocal than ever before in

demanding freedom for Geagea. Last month, Patriarch Sfeir declared that

the release of Geagea "is an imperative precondition" for national

reconciliation in Lebanon.[15]

In early May, the Qornet Shehwan Gathering, a coalition of mainstream

Christian politicians, issued a statement calling for his prompt release.

In light of the Christian community's overwhelming support for Geagea's

release, many in the Muslim political establishment have begun to quietly

express their support for a pardon (e.g. Jumblatt said recently that he

would not necessarily object to it).

According to some reports, this growing domestic consensus

has led American officials to begin pressing for Geagea's release.[16]

This would require either a special presidential pardon or a new general

amnesty by parliament, neither of which can happen without explicit

authorization from Damascus. Leaks to the press by political sources close

to Syria suggest that a special presidential pardon that would restrict

Geagea's political activity has been under consideration for some time.

However, Geagea is rumored to have rejected any restrictions on his

freedom of expression.

Notes

[1]

See Lewis W. Snider, "The Lebanese Forces: Their Origins and Role in

Lebanon's Politics," The Middle East Journal, Vol. 38, No. 1,

Winter 1984.

[2]

Theodor Hanf, Coexistence in Wartime Lebanon: Decline of a State and Rise

of a Nation (London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 1993), p.301.

[3]

Jonathan C. Randal, Christian Warlords, Israeli Adventurers, and the

War in Lebanon (New York: Vintage Books, 1984), p.122.

[4]

Muhamad Mugraby, "Lebanon, a Wholly Owned Subsidiary," Middle East

Quarterly (Vol. 5, No.! 1), March 1998, p.14.

[5]

"Lebanon observes mourning day to protest church bombing," United Press

International, 28 February 1994.

[6]

United Press International, 23 March 1994.

[7]

"Washington tight-lipped on Geagea to avoid jeopardizing its Mideast 'achievements',"

Mideast Mirror, 27 April 1994.

[8]

Al-Safir (Beirut), quoted in "Hrawi: Geagea could have redeemed

himself by subscribing to the post-Taef arrangements," Mideast Mirror,

25 April 2004.

[9]

Amnesty Interna! tional, "'Lebanese Forces' Trial Seriously Flawed," 24

June 1995.

[10]

"Justice holds death in the wings," The Independent, 27 January

1997.

[11]

Stephen J. Stanton,

Report and Analysis Concerning the Trial and Verdict of Samir Geagea and

the Co-Accused in the Case of the Bombing of the Church of Sayyidat Al

Najjat Zouk Mikayel, 20 November 1996.

[12]

The ruling also noted the court's rejection of solid alibis by two

defendants in the church bombing trial. A copy of this ruling can be

downloaded in

pdf

format from the Lebane! se Forces web site.

[13]

Quoted in Mideast Mirror, 26 June 1995.

[14]

Al-Safir (Beirut), 14 November 2002.

[15]

Al-Nahar (Beirut), 19 April 2004.

[16]

L'Orient Le Jour (Beirut), 12 June 2002, citing report by the

Kuwaiti daily Al-Siyasa.

2004 Middle East

Intelligence Bulletin. All rights reserved. |