|

| A

Syriac shepherd on guard near his flock. (photo: Karen Lagerquist) |

“We lived in terror” is how

a Syriac Christian villager in the Tur Abdin region of southeast Turkey

described life there for the last 16 years – years spent caught in the

middle of a dogged guerrilla civil war between Turkish military forces and

the secessionist Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK).

This conflict threatens to

empty the Syriac Christian heartland and is one more case of the pressure

on Christians to leave Turkey. Memories of the massacre of 1.5 million

Armenians in Turkey in the early 20th century and the violence unleashed

against Greeks in Istanbul in September 1955 are fresh enough to inspire

Tur Abdin’s Christians to flee.

Tur Abdin’s once vital

Syriac Christian population of about 80,000 has fallen to about 2,500. Yet,

to those Syriac Christians who remain in Tur Abdin (Syriac for “Mountain

of the Servants of God”), the arid mountainous land between the Tigris

River and the Syrian border is their holy land. Christianity there dates

to the early first century and to this day Syriac Christians celebrate

liturgies in Turoyo – a dialect of Aramaic, the language used by Jesus

Christ and the apostles.

A cease-fire between the

Turkish govern-ment and the Kurds means conditions in the region are

slowly improving. Fighting dropped off sharply since the 1999 capture of

PKK commander Abdullah Ocalan, who ordered his followers to withdraw from

Turkey into northern Iraq.

The PKK has changed its

strategy and says it wants to campaign peacefully for the rights of Kurds

and has dropped the demand to establish an independent Kurdistan. In 2002,

it changed its name to the Congress for Freedom and Democracy in Kurdistan

(KADEK). However, the move has been dismissed as a sham by the Turkish

authorities; the European Union has placed it on its list of terrorist

groups.

|

|

Binyamin is a Syriac mountain village. (photo: Karen Lagerquist) |

With the help of an economic

recovery program, dirt roads have been paved and the number of bus routes

into area villages has increased.

Virtually all military

checkpoints have been removed and freedom to travel has returned. The

spin-off to these improvements is that the tourist industry has been

revived and new hotels, restaurants and even Internet cafes have opened.

Turkey has applied for

European Union membership, but the EU says Turkey still needs to improve

its political and human rights record and to reform its oppressive

minority laws before the country can be admitted.

In the decades following

World War I, many of the region’s churches fell into disrepair, becoming

unusable. Muslim extremists and local Turkish government officials

hindered restoration efforts often by denying construction permits.

Further restrictions were

imposed on the Syriac Christians after the Lausanne Treaty of 1923, when

the community was not listed as a distinct minority whereas official

status was given to Turkey’s Armenian, Greek and Jewish citizens. For this

reason, the government prohibited Syriac Christians from operating its own

schools and interfered with church administration.

Now suddenly, after decades

of being denied basic rights, the Syriac Church, Catholic and Orthodox, is

permitted to teach freely its own language – a century-old ban that has

threatened the survival of the ancient language.

|

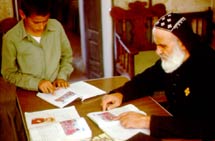

| A

Syriac Orthodox monk instructs a village boy in Aramaic. (photo: Chris

Hellier) |

“We have big hopes for the

future because the political climate has changed,” said Father Gabriel

Akyuz of the Syriac village of Hah. “If we are accepted into the EU our

future will be even more secure.”

In Tur Abdin’s two main

cities, Mardin and Midyat, dusty marketplaces are busy with shoppers. Boys

weave through the crowds energetically chasing down scuffed footwear with

offers of a quick shoe shine. Inside the shops, people are bargaining,

buying and selling – a sure sign of the improving economy. The language

shifts from Arabic, Kurdish and Turkish – only the Christians understand

Aramaic, which is used for the liturgies of the church.

Mixed in the crowded streets

are Kurdish women with facial tattoos as well as devout Muslim women in

their all-covering black peces or burkas. Yet each community shares

respect and understanding for the other. They speak the same mix of

languages, shop at the same stores, attend school and play together. The

differences are fewer than the similarities. One 12-year-old Kurdish girl

playing outside a church gate said: “The only difference is that we go to

mosque and they go to church.”

“We have no problems with

Muslims. They are our neighbors, friends, colleagues and students,” a

schoolteacher from Mardin said. She added that her Christianity has never

caused a problem.

But these are not the views

of all Christians from Tur Abdin. Opinions differ, sometimes drastically,

depending on the city or village, or who may be listening.

“We are not free,” said one

church official who spoke on the condition of anonymity. Then he added, “I

am not comfortable talking about these things,” citing a Tur Abdin priest

who, after speaking to a journalist about the 1915 Christian genocide in

Turkey, faced criminal charges.

The hillside city of Midyat

looks down over the valley as a great amphitheater.

Its decorative houses,

crafted by traditional Christian stone carvers, ascend the hillside

step-like – one a little higher than the next. Dome-shaped bell towers and

slim minarets pierce its skyline. But the city’s famed Christian stone

carvers have all left. The Christian population, once a majority, now

numbers some 100 families.

Midyat is also famous for

its tradition of Christian artisans specializing in the fine art of

filigree – fashioning silver wire into jewelry, vases and bowls. With

fewer and fewer Christians to pass on the tradition, it is being taught to

Muslim apprentices. Muslims now own most of the shops surrounding the

city’s central square.

One of the few remaining

Christian shop owners is Gebro Tokgoz. When he was a child, he learned the

silversmith trade from his grandfather. He can only guess how far back the

tradition goes. Mr. Tokgoz hopes to continue it for at least one more

generation with his eldest son.

Conversation inside the shop

shifts between Turkish, Arabic and Kurdish.

|

|

Faithful gather for liturgy at the Deyrulzafaran Monastery outside

Mardin. (photo: Karen Lagerquist) |

Mr. Tokgoz gets along well

with his Muslim clients and neighbors, including the police who stop in

for tea and a chat. But Mr. Tokgoz is uncomfortable with discussing the

future of Turkey’s Syriac Christians. In fact, the moment the police enter

the shop, any conversation about Christianity comes to an abrupt halt.

Once the police leave, the

conversation picks up again. When he is asked again about the future, Mr.

Tokgoz stares back with sharp hazel eyes and just shrugs. For him and most

people in the area there is little time to think about politics. Their

days are consumed with making a living – he spends 12 hours a day, six

days a week tending to customers and crafting jewelry – until Sunday when

all the Midyat jewelry shops close. A wall of metal security doors then

hides the silver and gold sparkle of shop windows.

The main roads leading out

from the center of Midyat curve through the hilly countryside into a vast

network of little villages – some exclusively Christian, others mixed.

Sixteen miles outside Midyat

is a hairpin turn where the road rises into the hills. What follows is a

roller coaster of hugging curves and hair-raising drops. It is hard to

believe this was a dirt road until 2001.

Along this road the splendid

bell tower and church of the village of Hah appear. Fifteen Christian and

two Kurdish families live here, but in spite of its small size, it has a

rich history dating to the beginnings of Christianity. Once known as “the

place of 40 churches,” a casual stroll through narrow streets reveals

ancient carved stone blocks layered between rock walls.

“We can only imagine what is

buried underneath here,” the village mukhtar, or mayor, Habip Dogan,

said while standing before a row of ancient columns recently dug up during

church renovations.

|

Syriac Christians in

Turkey

Turkey’s Syriac Orthodox

Church is the nation’s largest Christian denomination. According to a

2001 report by the U.S. Department of State, there are an estimated

15,000 Syriac Orthodox Christians in the country.

The Syriac Orthodox

Church is led by Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas, who resides at the

Mar Ephrem Monastery in Ma`arat Sayyidnaya, near Damascus.

Some 2,000 Syriac

Catholics, whose ancestors embraced full communion with the Church of

Rome, remain scattered in small communities in Turkey’s southeast.

Both of these churches

use Aramaic in their liturgies, which are dominated by the twin themes

of sinful unworthiness and majestic redemption.

Syriac Christians trace

their origins to the early Christian community at Antioch, mentioned

in the Acts of the Apostles. |

In the center of the village

stands a castle. It is the home of four Christian families. Each family

occupies a corner. To the villagers of Hah the castle represents a part of

their history and, more important, it is a symbol of their suffering and

great will to survive.

In 1915 the villagers

barricaded themselves behind the castle’s walls as militant Turkish

nationalists brutally murdered the region’s Christians. For two months

they held fast and when it was over everyone from Hah survived.

Through the castle’s main

gate a staircase leads to the corner home of the mayor, his wife and six

children. It is a traditional home consisting of two large rooms and a

kitchen.

The family room is the

largest room of the house with aqua walls and a high domed ceiling.

Opposite a colorful replica of da Vinci’s “Last Supper” looms a larger

than life portrait of modern Turkey’s founding father, Kemal Ataturk, who

glares over the sitting area. Mr. Dogan admires him but admits the

portrait is there mostly for the benefit of visiting government officials.

This one room is where most

of the family’s activities happen – where they eat, receive guests and

sleep, except during the summer when the sleeping area shifts outside to

the courtyard, beneath the stars.

|

| The

region of Tur Abdin in southeast Turkey is rich in historic

buildings. (photo: Chuck Todaro) |

Summer is a busy time of

year for the villagers. From the break of day to evening the entire

village empties into the fields – the mayor included. He too has to look

after his plot of land. In his spare time, he can be found at the church

teaching Aramaic to children or acting as a tour guide. Last summer, the

village had nearly 4,000 guests – and for these hospitable people that

does not just mean pointing out landmarks and answering questions.

Hospitality often means offering lunch or even a place to sleep.

The village’s schoolhouse is

in a small rectangular building next to the church. Its one room is where

Hah’s 17 children, from grades one through five, are taught.

“This is not as difficult as

you might think,” said the school’s teacher. Yet he does complain of the

few materials the Turkish government gives students, forcing children to

share books.

After graduating from

primary school, village boys board at a monastery and attend middle and

high school in either Midyat or Mardin. But for the majority of girls,

education ends with fifth grade.

Shaking his head Mr. Dogan

admits that, after this year, his daughter, Victoria, will be staying home

with her mother.

“I am afraid for her,” he

sighed. When asked what could happen he shoots back: “Who knows. I just

hope it will be better in the future for the younger ones.”

The fear he and most

Christian villagers feel for their children stems from a history of

marriageable girls being kidnapped.

Though Mr. Dogan will not

utter the word, the village priest, Father Gabriel Akyuz, does.

“Kidnapping,” he blurted out, but only after checking to see that no one

was listening. “It has happened before. Yes, 20 years ago, 15, 13 years

ago. We are now very aware.”

|

| Syriac

Christian children are the hope of the future. (photo: Chuck

Todaro) |

Archdeacon Melfono Gulten

from Mar Gabriel Monastery acknowledges that kidnappings took place but

said: “It is a fear that belongs in the past. I think the teachers are

better trained now and this new generation is a more understanding one.

But it needs time.”

And other village children

seem to agree – including Christians Hazni and Nahir, both 17, who attend

Midyat high school. They say that they have never had a problem in school

caused by their religion. They even seemed a bit surprised by the

question.

From the outsider’s point of

view this is an exciting period for the Syriac Christians of Tur Abdin.

But those living there feel frightened; they find themselves at a

crossroads. They are not really sure which road to take, not knowing where

it will lead.

“I wish to be optimistic

about the future, but that is not reasonable,” said one church official.

“All the decision-making is essentially out of our hands and we find

ourselves living a wait-and-see reality.”

“There is nothing certain

about our future,” added Mr. Dogan.

“It is an open book.”

Chuck Todaro reports from

the Middle East and Eastern Europe.

www.cnewa.org