|

HISTORY

Ph.D. in Assyriology and Northwest Semitic Epigraphy, the

University of Tübingen, 1984

Professor, Department of History and Archaeology, AUB, since

October 2001

Chair, Department of History and Archaeology, AUB, from 2010

to 2013

Chair, Department of History and Archaeology, AUB, from

October 2001 to October 2004

Associate Dean, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, AUB, from

October 1, 2004 to September 30, 2009

Joined the Department of History and Archaeology in 1985.

Co-director of the Beirut Excavations: Site BEY 020 between

1994 and 1997

Co-director of the Tell el-Burak and Tell Fadous-Kfarabida

Archaeological Projects since 2001 and 2004 respectively.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

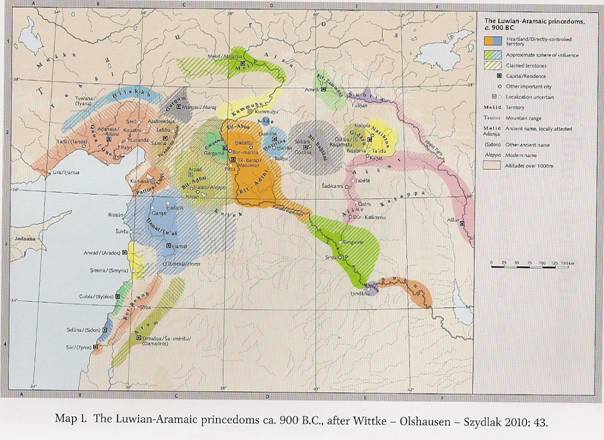

This chapter presents a survey of the history of the Aramaeans

of Syria from their origin and state formation untill the end of

their existence as independent polities; it takes into account

the latest written and archaeological evidence. Emphasis will be

laid on the formative period of Aramaean history, the

understandind of which has drastically changed in the recent

discoveries.

1.

GEOGRAPHICAL AND CHRONOLOGICAL SCOPE

The geographical scope of this coincides roughly with the bordes

of the modern state of the Syrian Arab Republic, infringing in

the north on the Amuq Valley and the slopes of the Amanus

Mountains, which are situated in Modern Turkey. It is within

this geographical space that we can trace the origin and

development of the Aramaean states of ancient Syria.

[1]

Chronologically, this chapter deals with the Iron Age I

and the larger part of the Iron Age II (ca. 1200-622 B.C.), a

period that witnessed the rise and decline of the Aramaean

polities. After this period, and in spite of the fact that

Aramaean culture continued to thrive, these polities ceased to

exist. Their political history thus starts after the collapse of

the Late Bronze Age city-states and ends with the Assyrian

conquest of Syria and their incorporation into the territory and

administrative system of the imperial Assyrian state.

It is important to stress in this context the fact that Syria

toward the end of the Late Bronze Age had a geopolitical

landscape that was totally different from the one provided by

the Neo-Assyrian annals, the Iron Age Hittite-Luwian, and the

Aramaic royal inscriptions. [2]

All the kingdoms that

1.

Cf the map in the frontispiece.

2.

For the Late Bronze Age kingdoms of Syria, see Klengel 1992.

existed in the 2nd millennium B.C. disappeared and were replaced

by new polities, some ruled by Luwian-speaking dynasts and some

ruled by Semitic-speaking Aramaean rulers. It is the history of

the latter kingdoms that is the focus of this chapter.

However, the history of the Aramaeans of ancient Syria is

closely connected with that of the Neo-Hittite or Luwian states.

The latte rare “rump” states that were created from and on the

ruins of the Late Bronze Age Hittite Empire.

[3] Newly discovered Luwian

inscriptions [4] have led to the

conclusion that the vacuum created by the collapse of the

Hittite Empire around 1200 B.C. was filled immediately—but only

partly –by surviving polities whose rulers were of Hittite royal

descent. Not only did these local dynasties continue to rule but

they expanded their territories at the expense of the former

Late Bronze age Syrian kingdoms.

New epigraphic material reveals that next to the kingdom of

Carchemish, which had survived the collapse of the Hittite

Empire [5], another state called

Walastin or Palistin was immediately formed and claimed dominion

over a large part of central and western Syria during the early

Iron Age, in the years immediately following its collaps.[6]This

new kingdom, which was ruled by a local dynasty of Hittite

descent, was founded on the ruins of the former kimgdom of

Mukish in the Amuq plain, with Tell Tayinat as its capital.

This is suggested by the inscriptions of its rulers, Taitas,

which were found in Aleppo and Hamath.

[7] This epigraphic evidence raises the possibility that

local dynasty (next to that of Carhemish and Malatya) survived

the Hittite Empire’s collapse [8]

and continued to rule in the tradition of the former Hittite

state over a territory stretching from the Amuq plain to the

Orontes Valley, including Aleppo and Hamath. These Neo-Hittite

or Luwian states were the direct neighbors of Aramaic-speaking

communities and included probably among their population large

groups of the latter. So both the territory and the history of

Aramaeans and Luwians are imbricated and often difficult to

disentangle for lavk of sufficient documentation. This is mainly

true for the period of formation of the Aramaean states durind

which the political landscape of Syria appears to be

3.

Harrison 2009b; 187.

4.

Hawkins 2009

5.

Hawkins 1988; see also Klengel 1992; 183f

6.

Harrison2009a; fig. 1

7.

Hawkins 2011

8.

Harrison 2009a: 174

”fragmented ”, or ”balkanized”[9].

As a result, any history of the Aramaeans of ancient

Syria

will have to take into account this close interconnection.

2.

THE SOURCES FOR A HISTORY OF THE ARAMAEANS OF ANCIENT SYRIA

2.1 The Written Record

The first problem that the historian of the Aramaeans of ancient

Syria faces is the scarcity are the annals of the Middle-and

Neo-Assyrian kings,[10] the

Luwian[11] royal inscriptions,

and the inscriptions left by the Aramaeans themselves.[12]

The biblical account (mainly 1 Kgs 11: 23-25;

15:18;20:1-34; 22: 1-4; 2 Kgs 6:8-33; 7:1-8; 7-15;12:18-19;

13:3-7, 24-25;15: 37; 16:5-9), which often deals with e tens

relations between the Israelite and Aramaean kingdoms has be

used with great caution. It is mainly relevent for the hisory of

the Aramaean kingdom of Aram-Damascus.[13]

2.2 The Archaeological Record

In the absence of a comprehensive corpus of written sources

covering the entire period of Aramaean history, one has to tur

nto the archaeological record to try and fill in the gaps left

by the texts. This task is not easy for here, too, one is faced

with the problematic and lacunal nature of the evidence. Until

the end of 20th century, little was known about the Iron Age I,

which is the period that saw the formation of the Aramaean

states. Little was also known about the layout and organization

of the Aramaean cities and territories in the Iron Age II

because of the very limited number of excavated sites with

substantial Iron Age remains. Apart from the evidence from early

20th-century exacavations (Tell Halaf,

[14]

9.

Harrison 2009b: 187.

10.

Grayson 1991; id. 1996; Tadmor 1994; Leichty 2011.

11.

Hawkins 2000.

12.

KAI 201-227; Abou Assaf – Bordreuil – Millard 1982; Biran –

Naveh 1993; iid; 1995; Schwiderski (ed.) 2004, Pardee 2009

a; id. 2009b.

13.

Kraeling 1918; Unger 1957; Pitard 1987; Reinhold 1989;

Axskjöld 1998; HafÞ`orsson 2006.

14.

Von Oppenheim 1931; id. 1943; id.1950; id. 1955; id. 1962.

Tell Fekheriye,[15] Zincirli,[16]

Tell Tayinat, [17] and

Hamath),[18] no published

information was avaible. In spite o fits importance the evidence

from the above-mentioned sites gave only a truncated view of the

Aramaean settlement. It first focused exclusively on large urban

sites and within these settlements on the upper cities and their

Iron Age II monumental architeculture. It entirely neglected the

lower cities where the domestic and industrial quarters were

located as well asthe small rural settlements.

With few exceptions, little attention was also given in these

eccavations to statigraphy and to the establishment of reliable

pottery sequences.[19] This

failure has led to a major difficulty in interpreting the

results of surveys that covered large areas of the Syrian

territory in the 2nd half of the 20th century. Little can be

gathered about the Iron Age occupation from most of them because

scholars were unable to identify and to determine clearly the

nature and date of the Iron Age pottery. So in spite of the

large number of surveys only the results of most recent ones,

such as those at Tell Tayinat[20]

and the Euphrates,[21] revealed

substantial information about the settlement pattern and

distribution during the Iron Age. Real progress has nevertheless

been made in the last two decades regarding the Iron Age

archaeology of Syria. Next to surveys, new excavations such as

those of Tell Afis[22] and Tell

Qarqur[23] have yielded refined

pottery sequences ranging from the Iron Age I until the end of

Iron Age II, allowing a better understanding of the

characterstics of the Early Syrian Iron Age. This new evidence

has changed our understandind of the situation that prevailed in

the period immediately following the collapse and shed new light

on the origin and formation of the Iron Age polities of ancient

Syria.

In addition to these new excavations, work recently

resumed on serveral major sites that had been excavated at the

beginning of the 20th century yielding extremely important new

archaeological and epigraphic evidence, allowed for new insights

into the history of some Aramaean kingdoms.

15.

McEwan et al. 1858.

16.

Von Luschan 1893; id. 1898; id. 1902; id. 1911; id. 1943.

17.

Haines 1971.

18.

Fugmann 1958 and Riis 1948.

19.

Jamieson 2000: 261-263 and n. 7.

20.

Harrison 2009a.

21.

Wilkinson 1995.

22.

Mazzoni 1995; ead. 2000a; ead. 2000b; ead. 2000c; ead

Cecchini – Mazzoni (eds.) 1998; Venturi 1998; id. 2000.

23.

Dornemann 2002 and id. 2003.

These sites are Tell Fekheriye[24]

and Tell Halaf[25] on the Khabur,

Tell Ahmar[26] on the Euphrates,

Zincirli[27] on the eastern

slopes of the Amanus Mountains, Tell Tayinat[28]

in the plain of Antioch, and Aleppo[29]

in central-northern Syria.

2.3 Origin of Name ’’Aramaean’’

Before dealing with the history of the Aramaean of ancient Syria

it is important to define the origin of the appellation ”Aramaeans.”

This designation dervies from the geographical name Aram, which

appears for the first time in connection with groups called

ahlamu[30]

in the Middle–Assyrian texts of Tiglath-Pileser I

(III4-1076 B.C.) and Assur-bel-kala (1073-1056 B.C.).[31]

The inscriptions of these 11th-century B.C. kings mention

ahlamu of the land Aram or ahlamu-Aramaeans,[32]

the land Aram indicating the area between Khabur and

Euphrates [33] as well as the

west bank of the Euphrates, [34]

since these ahlamu-Aramaeans moved freely as far as Jabar

Bishri, Palmyra, and

Mount Lebanon.

[35] It is interesting to note in

this context that later Aramaean dynasts never refer to

themselves as Aramaeans or their country as Aram, with the

exception of the king of Aram-Damascus since his kingdom was

also called Aram. In the 8th century B.C. aramaic inscriptions

of Sefire (KAI 222-224) expressions ”All Aram” and ”Upper and

Lower Aram” were variously interpreted

[36] but it can be safely argued that ”All Aram” refers

to a geographical area [37] that

included the territorieso f the Aramaean and non-Aramaean

kingdoms united in the coalition against Mati’el of Aprad, and

that roughly covers

24.

Bonatz – Bartl – Gilibert – Jauss 2008: 89-135.

25.

Cholidis – Martin 2002; iid (eds.) 2010; iid. (eds.) 2011;

Baghdo – Martin – Novak – Orthmann (eds.) 2009; iid. (eds.)

2012; Novak 2010.

26.

Bunnens 1995a and Roobaert – Bunnens 1999: 167-172.

27.

Schloen – Fink 2009a; iid. 2009b; iid. 2009c.

28.

Harrison 2009a and id. 2009b.

29.

Kohlmeyer 2000; id. 2009, id. 2012 ; Gonnella – Khayata –

Kohlmeyer 2005.

30.

Postgate 1981: 48-50 and Lipinski 2000a: 37f.

31.

Nashef 1982: 34f. For earlier occurences of the term Aram,

see Reinhold 1989: 23-38 and, more recently Lipinski 2000a:

26-40.

32.

Nashef 1982.: 35.

33.

Ibid.

34.

For the later use and meaning of the term Aram, see the

review in Sader 2010: 276f.

35.

Grayson 1991:23, 37f.

36.

Sader 1987: 279-281.

37.

Puitard 1987:178-179; Fitzmeyer [2] 1995: 65-68; Grosby

1995; Sader 2000: 70; Kahn 2007.

the boundaries of modern Syria, while ”Upper and Lower Aram” may

refer to North and South Syria, respectively.[38]

So Aram is a geographical term that refers at times to

part and at others to all of the Syrian territory in the Iron

Age, hence the appellation ”Aramaean” given to the

1st-millennium B.C. inhabitants of Syria.

3. The ARAMAEANS IN THE IRON AGE I (1200-900 B.C.):

FROM KIN-BASED GROUPS TO POLITIES[39]

3.1 The Texts

The foundations of the Aramaean were laid during the three

centuries that followed the collapse of great Hittite Empire

(ca. 1200-900 B.C.). The only texts that deal with the Aramaean

population of Syria in the Iron Age I are the above –mentioned

Middle Assyrian royal annals of Tiglath-Pileser I and

Assur-bel-kala.

Tiglath-Pileser I says in one of his annals: ”I marched

against the ahlamu-Aramaeans… I plundered from the edge

of the land of Suhu to the city of Carchemish of the land Hatti

in a single day. I massacred them (and) carried back their

booty, possessions, and goods withi’out number. The rest of

their troops…crossed the Euphrates. I crossed the Euphrates

after them….I conquered six of their cities at the foot of Mount

Bishri, burnt, razed, (and) destroyed (them)…”[40]

In another passage the same king says that he crossed the

Euphrates 28 times, twice in one year, in pursuit of the

ahlamu.Aramaeans. Again, he claims to have defeated them

”from the city of Tadmar of the land Amurru, Anat of the land

Suhu, as far as Rapiqu of Karduniash.”

[41] Elsewhere he says: ”I brought about their defeat

from the foot of

Mount Lebanon,

the city Tadmar of the land Amurru, Anat of the land Suhu, as

far as Rapiqu of Karduniash”. [42]

Assur-bel-kala [43] also

led several campaigns against various contingents or caravans of

Aramaeans (KASKAL sha KUR a-ri-me) in northeast Syria.

38.

Lipinski 2000a: 214 identifies “Upper Aram” as the sphere of

influence of the kingdom of Bit Agusi and “Lower Aram” with

that of Aram-Damascus.

39.

For this formative phase of the Arameans history, see also

Aader 2000; ead. 2010; ead. Forthcoming.

40.

Grayson 1991: 23.

41.

Grayson 1991: 26-38, 43.

42.

Grayson 1991: 23, 37f.

43.

Grayson 1991: 101-103.

The Akkadian term ahlamu, which is used to refer to the

inhabitants of Aram, referred from the 2nd millennium B.C. to

tribal groups, leading scholars to infer that the groups

referred to as Aramaeans had a tribal social structure. The fact

that the Assyrians called the inhabitants of Aram ahlamu,

a term ”with the general range of ’barbarian’”

[44], has led to the assumption

that Aramaeans were semi-nomadic agropastoral groups.

3.2 The Archaeological Evidence

The archaeological evidence seems to match the general picture

provided by the 11th-century B.C. Assyrian texts, not only in

the valley of the Euphrates, but throughout North Syria. This

evidence comes from both surveys and large-scale excavations.

Surveys were conducted east of the Euphrates, in the Jabbul

area, in the Orontes Valley, and in the coastal area.

[45] The available survey data

indicates an increase in the number of Early Iron age

settlements as compared to the previous Late Bronze Age both

east and west of the Euphrates. [46]

A large majority of them were new foundations of a small

size, indicating ”a ’dispersal’ of the population into small,

rural settlements….” [47] The

so-called ”cities” of the Aramaeans mentioned by Tiglath-pileser

I in the 11th century B.C. and by Assur-dan in the 10th century

B.C. [48] are certainly to be

understood as part as this early Iron Age settlement process.

The survey results were confirmed by those of large-scale

excavations, which have demonstrated that the overwhelming

majority of excavated early Iron Age I sites had an economy

based predominantly on agriculture and small catte breeding with

strong evidence of production, storage,

44.

Grayson 1976: 13 n. 70.

45.

For these surveys, see Braidwood 1937; Maxwell Hyslop et al.

1942-1943; Braidwood – Braidwood 1961; van Loon 1967;

Courtois 1973; Matthers et al. (eds.) 1981; Akkermans 1984;

Braemer 1984; Shaath 1985; Meijer 1986; Geyer – Monchambert

1987; Sapin 1989; Ciafardoni 1992; Schwartz et al. 2000:

447-462; Melis 2005; Janeway 2008: 126f; Harrison 2009a:

175f; Tsuneki 2009: 50.

46.

Wilkinson 1995; see also McClellan 1992: 168f; Bartl – al-Maqdissi

2007: 243-251; Fortin 2007: 254-265; Harrison 2009a:175f.

47.

Morandi Bonacossi 2007a: 86 observed that “the duffusion

throughout the country-side around Mishrifeh of dispersed

rural settlements depend on a larger central site located at

the geographical centre of the system, following a

´scattered´ model also found in the Syrian and Iraqi Jazirah

– which seems to constitute a developmental pattern shared

by northern Mesopotamia and inner Syria in the IA II and

III”

48.

Grayson 1991: 133.

and processing of food represented by silos, pithoi, and bread

ovens.[49] The rural and

egalitarian character of the sites is clearly indicated by the

architecture: each house had its own storage and work areas as

indicated, for example, in the well-preserved remains of Tell

Afis[50] and Tell Deinit.[51] Most 12th-11th century B.C. sites had no monumental public

buildings and contained only dwellings characterzied by domestic

installations such as tannurs, silos, and pithoi,

indicating food processing and storage. Tell Afis, for example,

displays in levels 7abc-6 (Iron Age IB) ”a regular plan with

rectilinear streets separating units of houses with inner

courtyards funrished domestic and industrial installations for

weaving, storage and probably dyeing.”[52]

as suggested for the southern Levant, the fact that Iron

Age I sites in Syria were also composed of agglomerations of

domestic structures would seem to confirm the complex

patriarchal familj as the fundamental social unit.[53]

This archaeological evidence may lead to the conclusion that

the new communities that appeared after the collapse of the Late

Bronze Age settlements in Syria were founded on new principles,

and ”sressed domestic autonomy and an ideology of categorical

equality between domestic groups,” as suggested by B. Routledge

[54] for the Jordanian Iron Age.

What happened toward the end of the late Bronze Age is that

people from within and from outside the cities ”began to

gravitate to new communities focused on mutual defense and

subsistence security.”[55]

3.3 A Population Continuum

The Middle Assyrian texts mentioned above confront of Aramaean

history with two main dificulties. First, they describe the

situation prevailing only in a specific area of Syria,

stretching from the Khabur to

Mount Lebanon.

On the other hand, the only population groups they refer to this

area the ahlamu-Aramaeans. Did this group from the entire

population of northeastern Syria or were they only its

agro-pastoral component? Was ”Aramaean” presence restricted to

the area mentioned

49.

Mazzoni 2000c: 121-124.

50.

See Chitti 2005 and Venturi 2005.

51.

Shaath 1985. The Iron Age II houses uncovered in Tell

Mastuma (Iwasaki et al. [eds.] 2009) seem to be in tradition

of these early Iron Age I dwellings.

52.

Mazzoni 2000c: 123.

53.

Routledge 2004: 128.

54.

Routledge 2004: 113.

55.

Ibid.

in the Middle-Assyrian annals or were these groups also present

elsewhere in Syria? Finally, were these ahlamu-Aramaeans

newcomers or the descendants of the Late Bronze Age population?

While the term ahlamu-Aramaeans may be understood

in the specific context of Tiglath-Pileser I’s annals as

refferring to agro-pastoral groups this does not imply that they

included only semi-normadic elements or that they were the only

inhabitants or social group of Iron Age I Syria . As G. Bunnens

rightly stated, ”there were no great shifts of population after

the collapse of Late Bronze Age society . Local rural

communities together with unstable, possibly but not necessarily

normadic groups such as the Ahlamu. . . became the primary

components of the political and social fabric, and the trible

replaced the former terriorial states as the basic unit of

collective organization.” [56]

In spite of clear regional differences, the recent

archaeological evidence clearly supports a population

continuum which is attested by the evidence of both the

language and the material culture. Regarding the linguistic

evidence, it supports continuity between the Late Bronze Age

West Semitic-speaking population, of which the ahlamu-Aramaeans

were part, and the later Aramaeans. The Emar texts show

continuity betwwen 2nd-millennium West Semitic and

1st-millennium Aramaic dialects and suggest that the Aramaeans

had been part of the local population of Syria since the Late

Bronze Age: ”Most of the roots occuring in the huge Amorite

documentation of upper Mesopotamia and northeastern Syria recur

later in Aramiac. Furthermore, several Amorite names . . . are

the forerunners of exclusively Aramaic anthroponyms...”

[57]

As for the archaeological evidence, when available it attests

the survival of Late Bronze Age architectural traditions,

industies, and other aspects of the material culture, more

specifically the local ceramic assemblage

[58] found at all excavated

sites. According to S. Mazzoni, ”the analysis of the local

pottery and elements of architecture, such as the plans of

domestic buildings in Ras Ibn Hani, Tell Sukas and Tell Afis,

has successfully demonstrated the native character of the local

Iron Age II population.”[59] This

continuity is also indicated by the fact that some early Iron

Age sites re-occupied Late Bronze Age settlements and a larger

number of them

56.

Bunnens 2000b: 16.

57.

Zadok 1991: 114.

58.

Fugmann 1958: 135; 266; Bounni – Lagarce – Saliby – Badre

1979: 243, 245; Lund 1968: 40-42; Venturi 1998: 128.

59.

Mazzoni 2000a 34.

continued to be settled in the Iron Ago II.

[60] So it can de safely assumed

that the settlers of the Iron Age I sites were part of the local

population of Syria and that the groups called ahlamu-

Aramaeans were also part of this population. The theory that was

widely spread 30 years ago and according to which the Arameans

are foreign invaders coming from the Syro-Arabian desert[61]

no longer holds in view of the recent archaeological and

epigraphic evidence. As B. Sass [62]

correctly puts it: ”Rather than as invaders, new on the scene,

the Aramaeans are rightly understood as a local element in

changing social condition.”

3.4 Northeast Syria between Assyrian pressure and

Neo-Hittite Expansion

What was the prevailing political situation in northeast Syria

in the Iron Age I according to the above evidence? The Middle

Assyrian texts do not refer to individual Aramaean polities but

only to an undifferentiated group called ahlamu-Aramaean

who were present in the area extending from the Khabur to

Mount Lebanon.

With the exception of the kingdom of Carchemish, which was in

the hands of a Neo-Hittite dynasty, northeast Syria in the Iron

Age I appears to have been occupied by rural settlements

controlled by a confederation of large kin-based groups referred

to as ahlamu-Aramaeans. These groups were not yet

organized in individul political entities and their settlement

was peaceful and resulted from the collapse of the large Late

Bronze Age urban settlements. No leading house or leader is

mentioned individully by name but these groups appear

nevertheless to have been well organized and armed, for they

were able to resist the mightly Assyrian army. They also

apparently enjoyed great wealth, as suggested by the expression

”their goods without number.” [63]

While the ahlamu-aramaeans resisting Assyrian

advances east and west of the Euphrates, the settlers of central

and northern Syria had to face the growing power of the land of

Palistin. This area, from the plain of Antioch in the west to

Aleppo and Hamath in the east, was being rapidly transformed

into a polity by the rise of the Luwian dynasty. Indeed, Taitas

appears to have conquered central and northern Syria as early as

the 11th century B.C. According to the archaeological evidence,

the situation

60. Venturi 2000:533-536 and table 1.

61. E.g. Duppont-Sommer 1949 and Malamat 1973.

62. Sass 2005:63.

63. See note 40, above.

in the conquered area was probably quite similar to that

prevailing in the northeast before this Neo-Hittite expansion.

Northeast Syria, the heartland of the Aramaeans, was

therefore pressured by the Assyrians in the east, and by the

Luwian Kingdoms of Carchemish and Palestin in the north and

west, respectively. This constant threat was instrumental in

creating a defense mechanism that to the regeneration of complex

socities.

3.5 The Regeneration of Complex Socities

It does not seem far-fetched to suggest that in the early stages

of the Aramaean state formation kinship or belonging to what B.

Routledge calls a ”founding house” or ”domestic group”

[64] was instrumental in creating the necessary

cohesion among the population and in formulating new

socioplitical relationship that cecame the basis of the emerging

state. As already argued, the textual and archaeological

evidence supports this assumption. This social organization may

be inferred also from the name later given to the new polity as

”House” of an eponymous ancestor.

Two main-factors may have prompted the regeneration of

complex societies toward the end of the Iron Age I in northeast

Syria. The first is the promixity of already established

Neo-Hittite kingdoms. It is important not to underestimate the

Aramaen states’ desire to emulate the successful Luwian models,

which had survuved the great collapse and the territories of

which were interwoven with those held by Aramaen groups. T. S.

Harrison is right in stating that the diverse cultural and

ethnic milieu may have ”provided the stimulus that forged the

small vibrant nationstates that would come to define Iron Age

civilization in this region.” [65]

So, ”the survival of institutions or ideas from before the

collapse,” [66] embodied in the

Luwian polities may have played a role the formation of Aramaen

centralized states.

The second factor that may have accelerated the regeneration

of complex societies and the creation of centralized states in

Aramaean-held territories is trade. G. M. Schwartz notes that

”trade with external societies has been identified as a crucial

variable in the revival of complex societies”;

[67] indeed, it may have played an important role in

the

64. Routledge 2004:113.

65. Harrison 2009b: 187.

66. Schwarz 2006: 10.

67. Schwarz 2006: 11.

regeneration of such societies Iron I Syria. There is a clear

indication in the archaeological and written record that these

Iron Age I communities witnessed a growing economic power

represented by the strorage of production surpluses, local

industry, and trade activity. The Eurphrates was one of the most

important trade routes in ancient Syria and, as already noted,

it was under the control of the Aramaeans, who may have quickly

resumed trade and exchange. This trade activity is clearly

attested in the rich booty from the Aramaean groups on the

middle Euphrates collected by Tiglath-Pileser I in the 11th

century B. C. and by Assurnasirpal II at the dawn of 9th century

B. C.: precious matals, ivory, sheep, and dyed textils.

[68] This revival of trade activity is attested as early

as early as the 11th century at several sites by the presence of

imprtant pottery. [69] The

settled communities could have intensified their own level of

production yo participate in this acvtive commerce, as evidence,

for example, by the flourishing textil industry attesed in Tell

Afis[70] and in the sheep and

dyed textiles that are constantly mentioned as part of the booty

collected from Aramaen groups.

It was this growing prosperity and increased contact with

the wider world that may partly explain the growth of the

settlements and the rise of new complex centers in syria in the

Iron Age II. It is highly likely that the need to protect the

settled territory and the privileges and wealth acquired by

controlling the main trade routes wsa instrumental in leading

Syria toward rapid urbanization, which in turn paved the way to

the emergence of centralized states.

So the creation of the Aramaean polities started with

large kin-based group—around which smaller domestic groups may

have clustered—establishing control over a territory they had

settled and which they secured with strongholds. Once a group

had firmly established its control over a territory it was able

to expand in order to conquer more land for defensive,

strategic, or economic purposes. There is evodence in the

Assyrian records that the aramaeans had to use military force to

conquer or maintain control over settlemenys that were of

economic and/or strtegic importance for their survival. This was

the case in the conquest of Pitru, Mutqinnu,

[71] and Gidara[72] on the

western bank of the Euphrates as well

68. Sader 2000:69.

69. Riis 1948:114; Bonatz 1998; Mazzoni 2000a: 36; Venturi 2000:

522-528

70. Cecchini 2000.

71. Grayson 1996:19, 51, 64f, 74.

72. Grayson 1991:150.

as of many other cities that were previously held by the

Assyrian or by Luwian Kingdoms. The Neo-Hittite Kingdom of

Palistan lost large parts o fits territory to the Aramaean

kingdom of Bit Agusi and to Hamath: the first controlled

Aleppo—a key city on the way to Anatolia—and its area and the

second hamath and its area. Under the pressure of the newly

established Aramaean polities, this great Luwian kingdom, known

in the Neo-Assyrian annals as pattina-Unqi, shrank to its

original core around Tell Tayinat in the plain of Antioch. The

Aramaean kingdom of Bit Adini, on the other hand, conquered

territories that were in Luwian hands, such as Masuwari,

[73] Aramaean Till Barsib, and modern Tell Ahmar, a key

site contolling the crossingo f the Euphrates from east to west

that was conquered by Ahuni of Bit Adini, who turned it into his

main strongholh.

3.6 Territorial Organization and Consolidation of the State

Independent polities ruled by Aramic-speaking dynaste appear for

the first time in the late-10th-century B.C. annals of the

Neo-Assyrian king Adadnirari II (911—891 B.C.). Most of them are

characterized by a new naming:”house if PN” (Bit Bahiani, Bit

Adini, Bit Asali, Agusi) and their rulers are called in the

Assyrian annals and in some Aramaic inscrio’ptions ”sons of PN,”

the personal name in both appellations being that of the

historical or legendary founder of the state.

[74] There were, however, some exceptions to this rule:

The kingdom of Hamath was alwats called by the name of its

territory and never ”house of PN.” This may be explained by the

fact that after having been part of the land of Palistin, Hamath

may have been ruled by an offshoot of this Luwian dynasty, since

its 9th-century rulers, Parata, Urhilina, and his son Uratami,

bear Luwian names.

The other exception is the kingdom of aram-Damascus. This

kingdom was refferd to as Aram or Aram-Damascus in the Aramaic

inscriptions and the Hebrew Bible and as sa imerisu in

the Neo-Assyrian annals. Only rarely do these annals refer to it

as bit-haza’ili.[75]

Finally, the successors of Gabbar never call their kingdom Bit

Gabbari but refer to it by the name of the territory, ”Yadiya,”

or by that of its capital ”Sam’al.” Only the earliest ruler

mentioned in the Assyrian annals, Hayyan, is called ”Son of

Gabbar.” Here, again, the mixed Aramaean-Luwian character of the

ruling dynasty

73. Hawkins 1983.

74. Routledge 2004:124-128 recentiy discussed this issue.

75. Summ 4, T; Summ 9, rev. 3; ef. Tadmor 1994:138,186.

may have been the reason behind choosing the name of the

territory instead of the traditional tribal designation.

The Aramean kingdoms that developed in the territory of

modern Syria[76] are those of

Bit Bahiani on the upper Khabur, Bit Adini on the east and west

bank of the Euphrates, Bit Agusi in central north Syria from

Aleppo to the Syro-Turkish bordes, Hamath and Lu’as’ from the

Orontes Valley to the coast, and Aram-Damscus from Palmyra to

the Golan Heights, including the Lebanese Beqa’.

[77] Aramaean polities, like Laqe and Bit Halupe on the

Middle Euphrates and lower Khabur, and Nisibis and Bit Zamanni

in the Tue ’Abdin area, were short-lived and do not appear to

have initiated large.scale urbanization, since there is no

mention of their royal or fortified cities.

[78] They were incorported into the Assyrian provincia

system toward the moddle of the 9th century B.C.

When the Assyrian annals first mention these Aramaean

kingdoms all appear to have undergone large-scale urbanization.

The Assyrian texts always associate these urban settlements with

the person of the polity ruler by referring to them as his royal

(alanu sarruti-su) or his fortified cities (alanu

danuti-su). [79] Political

authority may be explained by the need ”to enhance the

managerial and coordinating capabilities of the emerging

leadership”. [80] As S. Mazzoni

correctly observed, urbanization was linked to the emergence of

”political entities based on territorial control and

exploitation,” which later achieved ”central administration and

a palaceoriented organization.” [81]

Urban centers with fortifications and monumental

buildings are widely attested in the archaeological record of

Syria from the 10th century onward in Hamath,

[82] Zincirli, [83] Tell

Halaf, [84] Tell Fekheriye,

[85] Tell

76. Sader 1987, Dion 1997, and Lipinski 2000a recentiy discussed

the political history of these kingdoms. Cf. also the map in the

frontispiece.

77. Lipinski 2000a: 298 claims that the Beqa’ Valley was in the

hands of the kingdom of Hamath in spite of the fact that the

provinces created by the Assyrians on the territory of

Aram-Damascus clearly include cities located in the Beqa’

Valley.

78. For their boundaries and their political role, see Lipinski

2000a: 77-117.

79. For these cities, see Ikeda 1979.

80. Cohen 1984:347.

81. Mazzoni 1994:329.

82. Fugmann 1958.

83. Von Luschan 1893; id. 1898; id. 1902; id. 1911; id. 1943;

see more recentiy Wartke 2005 and also Schloen – Fink 2009a; iid.

2009b.

84. Von Oppenheim 1950; id. 1955; id. 1962 and more recentiy

Cholidis - Martii in 2002; iid. (eds.) 2010; iid. (eds.) 2011;

Baghdo – Martin – Novak – Orthmann (eds.) 2009; iid. (eds.)

2012.

85. McEwan et al. 1958.

Afis, [86] ’Ain Dara,

[87] Tell Rifa’at, [88]

Tell Mishrife, [89] and Tell

Qarqur. [90] New urban

foundations such as that of Hazrak-Hatarikka continued all

through the 8th century B.C. and they are attested in both the

written and the archaeological record. .

[91] Almost all these urban centers were new foundations

and this fact may account for the drastic in thge toponymy of

the area.

Urbanization was accompained by an increase in the

number of small rural settlements mantioned simply as ”cities”

or ”towns” (alani), for lack of a specific name for this type

settlement. Shalmaneser III says in the account of his camaign

against Bit Agusi, for example, that he ”captured the city Arne,

his royal city. I razed, destroyed, and burned together with

(it) 100 cities in its environs”; . [92]

in the annals relating to the battle of Qarqar, the same king

says that ”he conquered the city of Ashtamakku together with 89

(other) cities, [93] which

belonged to the kingdom of Hamath; finally, in Tiglath-Pileser

III’s campaign against Damascus, the Assyrian king says that he

conquered ”591 town” of Damascus. [94]

This settlement pattern, consisting of an urban administative

center surrounded by the archaeological evidence.

[95]

The territory of the Aramaean polities was divided into

administarative districts the number of which varied from one

state to another. This may again be inferred from the Assyrian

inscriptions, which indicate, for example, that the kingdom of

Aram-Damscus, on the eve o fits transformation into an Assyrian

provunce, was dividedi nto at least 16 disticts[96]

while 19 districts of the land of Hamath were conquered by

Tiglath-Pileser III and ammexed to the Assyrian Empire.

[97] These districts may have

been organized around major urban centers. .

86. Cecchini 2005; Affani 2005; for a recentiy discovered

monumental Iron Age I temple, cf. Soldi 2009:106-116.

87. Abou Assaf 1990 and Kohlmeyer 2008.

88. Seton-Williams 1961 and id. 1967.

89. Morandi Bonacossi 2006 and id. 2007a.

90. Dornemann 2002 and id. 2003.

91. Mazzoni 2000a: 48-55.

92. Grayson 1996:46.

93. Grayson 1996; 38.

94. Ann 23,16’-17’; cf. Tadmor 1994:80f.

95. Morandi Bonacossi 2007a: 86; cf. note 47, above.

96. Pitard 1987:187.

97. Ann 19, 9-10 and 88-89; Ann 26, 5; cf. Tadmor 1994: 62f and

Radner 2006-2008a: 58-61 nos. 50, 54.

The bordes of these Aramaen territorial sttes were never

clearly defined and they were often the cause of armed

conflicts, echoes of which are occasionally found in written

record such as the conflict opposing Bar-Gayah of Kittika to

Mati’el of Arpad recorded in the Sefire inscriptions,

[98] or the one opposing sam’al to the kings of the

Danuna[99] and to Gurgum[100]

in the royal inscriptions of Kulmuwa and Panamuwa II

respectively, or, finaaly, the conflict opposing the kings of

damascus to the kings of Israel recorded in the Bible[101]

and in the recently discovered Aramaic inscription of Tell Dan.

[102]

In the 9th centuries B.C., state authority as well as

administrative and economic duties were concentrated in one

urban center and in the hands of a hereditary monarch. This

centraization process is evidenced in the building of new

capitals. Some Aramaean capitals were clearly new foundations

especially built to be the seat and the symbol of power of the

ruling dynasties. The most obvious examples are Hazrak, the

capitalo f the kingdom of Hamath and Lu’ as’ (KAI 202), and

Arpad, which became the new capitalo f Bit Agusi after the

destruction of Arne. Other cities, which had exised before, like

Sam’al, Qarqar, and Damascus, became with time the vital centers

of their respective kingdoms. This trend toward centralization

is clearly seen in the fact that Aramaean rulers of the 8th

century B.C. were no longer called ”sons” of their eponymous

ancestor, of whom they were the hereditary descendants, but by

the name of their capital: while in 9th century B.C. Hayyan is

called son of Gabbar, the 8th-century king Panamuwa is called

the Sam’alite. [103] The

traditional designation of the ruler as ”son of PN” seems to

have been abandoned in the 8th century B.C., since the Aramaeans

had adopted for themselves the title of king: Attarsumki and

Mati’el are kings of Arpad, [104]

Panamuwa is king of Yadiya, [105]

and Bar-Rakkab the king of Sam’al. [106]

Centralization created an organic link between the fate

of capital and that of the kingdom. The royal residence became

the life-giving organ

98. KAl 222-224

99. KAI 24.

100. KAI 215.

101. 1 Kgs 15: 20-22; 2 Kgs 6:12-15.

102. Athas 2003.

103. Ann. 3,4; 13,12; 27,4; cf. Tadmor 1994: 68, 87f.

104. KAl 222.

105. KAl 214.

106. KAI 216 and 217.

of the state and its destruction automatically led to the

collapse of the entire polity.

4. THE IRON AGE II: ARAMAEAN POLITIES AND THE ASSYRIAN

CONQUEST

The incorporporation of the newly established Arameaen kingdoms

into the Assyrian provincial system started as early as the

mid-9th century B.C. wuth the conquest of Bit Bahiani and Bit

Adini, two Aramaen kingdoms located east of the Euphrates on the

route from Assyria to the Mediterranean.. It was also in the

first half of the 9th century B.C. that the Aramaean

territorieso f Laqe and Bit Halupe were subdued by Assurnasirpal

II. They seem to have fallen later into the hands of the

Hmathite rulers. [107]

4.1 Bit Bahiani

Regarding Bit Bahiani, recent archaeological and epigraphic

discoveries in Tell Halaf have led the excavators to reconsider

the chronology of events and the succession of the rulers of

this Aramaean polity. [108]

Bit Bahiani is mentioned as early as the region of

Adad-nirari II, who receuved the tribute of Abisalamu, son of

Bahianu, [109] in the year 893

B.C. Two royal cities of Bit Bahiani---Guzana, modern Tell Halaf;

and Sikani, modern Tell Fekheriye, on the upper Khabur near Ras

elAin---are also mentioned, indicating that the kingdom was

founded as early as the 10th century B.C.

M. Novak[110] places

the foundation of the kingdom at the begining of the 10th

century B.C. and the rule of Hadyanu and his son Kapara, whose

inscription was written in cuneiform on the female statue of the

hilani toward the middle of the 10th century B.C. before the

first Assyrian campaign. M. Novak considors Kapara to be the

builder of the hilani and o fits imressive scorpion gate.

[111] He justifies a date in the 10th century for his

rule by

107. Lipinski 2000a: 105; Radner 2006-2008a: 55 n. 34.

108. Novak 2009: 97.

109. Grayson 1991:153.

110. Novak 2009: 97.

111. Novak 2010:12. The date proposed by Novak for the rule of

Kapara and the building of the hilani diverges from the 9th-century

date previously established by Moortgat in Oppenheim 1955 and

Hrouda in Oppenheim 1962 for the orthostats and small finds,

respectively, and the 8th-century date proposed by

Akurgal 1979 for the building of the hilani. Lipinski

2000a: 123,132 suggests that Kapara is a king of the Balikh area

who conquered Guzana in the second half of the 9th

centuiy B.C.

the absence of Assyrian influence on the inconography of the

hilani and on the palaeography and wording of the inscription.

[112] If this assumption is correct the hilani of Tell Halaf would

be the oldest building of this type in Syria known to date.

The date M. Novak suggestad for Kapara’s rule raises

various questions and clearly contradicts the generally accepted

9th-century date for that building.[113]

First, although both Kapara and his father bear clearly Aramaic

names, kapara refers to himself as ”King of Pale,” an otherwise

unknown kingdom. Lipinski suggests for Pale a readingo f ba-li

–e, and identifies it with an Aramaean kingdom that developed in

the Balih area. According to him, Kapara was the ruler of the

Balih kingdom around 830 B.C. [114]

and extended his dominion over Guzana during that period.

In M. Novak’s sequence, Kapara’s rule is followed by

that of the Aramaean house of Bahianu. Only Abisalamu is known

by name while another ruler, a contemporary of assurnasirpal II,

is simply referred to as ”son of Bahiani,”

[115] Bit Bahiani was conquered by the assyrians in the

first half of the 9th century B.C. and Guzana became the seat of

an Assyrian governor of Guzana, Samas-nuri.

The recently discovered bilingulal inscription of Tell

Fekheiye [116] has confused

scholars because the author of the inscription, Haddayis'i,

’ives himself and his father Shamash-nuri the title ”King of

Guzana” in the Aramic version. The problem that confronted

scholars was, first, to reconcile the dual status of these

rulers---how could they be kings Assyrian governors at the same

time?---and second, to determine the date of their rule knowing

that Guzana became an Assyrian proince before 866 B.C. A.R.

Millard[117] identified

Haddayis’i’s father, Shamash-nuri, with the above-mentioned

governor of Guzana. M. Novak, [118]

following E. Lipinski’s suggestion, identifies

112.Novak 2009: 94.

113.Sader 1987: 37.

114.Lipinski 2000a: 123,132. This date contradicts Novak’s

dating of Kapara’s rule.

115.Grayson 1991: 216.

116.Abou Assaf- Bordreuil – Millard 1982.

117.Abou Assaf- Bordreuil – Millard 1982: 112.

118.Novak 2009: 95.

Haddayis’i with Addu-remanni, the eponym of the year 841 B.C.

[119] Based on this identification he suggests that when

Bit Bahiani was incorporated into the Assyrian provincial system

the Assyrians appointed members of its Aramaean dynasty to be

governors of Guzana. Haddayis’i and his father would therefore

be members of an Aramaean royal house and not Assyrian

aristocrats. [120]

M. Novak’s interpretation, which attempts to solve the

duality of the titles of Haddayis’i and his father and to

reconcile the provincial status of Guzana with the existence of

”kings” of Guzana, is based on the unproven assumption that

members of local dynasties could be appointed governors of an

Assyrian province simply on the occurrence of Aramaic names of

some eponyms. This interpretation still needs to be

substantiated by more decisive evidence.

The recent archaeological evidence may have shed light

on the occupation sequence in Tell Halaf and on the nature and

date of some of its monuments but it has not yet solved the many

problems regarding the history of this Aramaean kingdom. It is

to be hoped that future results from Tell Halaf and from the

recent excavations of Tell Fekheriye, ancient Sikani, will yield

better insights into the history of this kimgdom.

4.2 Bit Adini

The relationship between the Assyrians and the Aramaean polity

of Bit Adini seems very clear, on the other hand: the texts

betray an unprecedented determination on the part of the

Assyrians to destroy and erase from the map all the cities of

Akhuni, son of Adini, the only ruler of Bit Adini attested in

the texts. The reason is obvious: the Assyrians needed to

control the key passage on the Euphrates, which was held by Bit

Adini. According to the Assyrian annals, Akhuni held the city of

Til Barsib, modern

119.One wonders why Haddayis’i, unlike his father, should have

had two names and why his Aramaic name should appear in the

Assyrian eponym list and not in the Aramaic version of the Tell

Fekheriye, inscription where he calls himself “King of Guzana.”

120. Abou Assaf- Bordreuil – Millard 1982:109f have cautiously

made this suggestion.

Tell Ahmar. Recent evidence [121]has

shown that this city, called in Hittite Masuwari, was ruled by a

Luwian dynasty. So Akhuni must have conquered it from the Luwian

dynasty, which ruled it. [122] It

is this event perhaps that led the Assyrians to end the

expansion of Bit Adini.

Akhuni -- and probably also his predecessors—who appears for the

first time in the annals of Assumasirpal II, were also able to

protect the large territory they controlled east and west of

the Euphrates, with no fewer than nine fortified cities that

Shalmaneser III would systematically attack and destroy over

four consecutive years (856-853 B.C). Til Barsib was renamed

Kar-Shulmanu-ashared, “Shalmaneser’s harbor,” and became the

seat of the Assyrian govemor.

Recent excavations at sites located in the territory of Bit

Adini have not yielded any new evidence for the Aramaean

occupation of Akhuni’s cities. The main city of Akhuni, Til

Barsib/Tell Ahmar, for example, which was excavated in the early

20th century by the French,[123]

was re-investigated recently by the University of Melbourne.[124]

According to the excavator, ”no remain dating from the

pre-Assyrian Iron Age were found in place in the middle and

lower city…and no stratified remains surely datable to the Iron

Age were found on the tell below the level of the Assyrian

palace….”[125] On the other

hand, the site of Tell Shuyukh Fawqani, which has been

identified with Burmar’ina, [126]

one of Akhuni’s fortified cities, has not yielded remains from

the early Iron Age [127] and

thus does not provide additional information on the history of

the Aramaean kingdom. Until more textual evidence becomes

available the history of Bit Adini will remain restricted to the

last years of its existence.

The Aramaean polities that developed west of the

Euphrates had a longer life span than those located east of the

river. They were able to establish centralized kingdoms, build

new capitals, and rule over a large territory for about two

centuries. Next to the information provided by the Assyrian

annals, details of their political history are available feom

their own local inscriptions.

121. Hawkins 1983 and id. 1996-1997.

122. According to Lipinski 2000a: 184, Ahuni was the son of a

Luwian ruler of Til Barsib, Hamiyata, who was a usurper.

123. Thureau-Dangin – Dunand 1936a nd iid. 1936b.

124. Roobaert – Bunnens 1999 with relevant bibliography in n.

5.

125. Roobaert – Bunnens 1999:167.

126. Bagg 2007: 55 with relevant bibliography.

127. Bachelot 1999:143-153.

This polity developed in central north Syria at the expense of

Bit Adini in the east and the kingdom of Palistin in the

northwest. Its political history is one of the best documented

by both Assyrian and local Aramaic inscriptions.

Its original territory, known as the land of Yakhanu,

is first mentioned in the annals of Assurnasirpal II.

[128] Its ruler, Gusi, is considered to be the founder

of the polity known later as Bit Agusi. He is also the founder

of its ruling dynasty, which can be reconstucted without gaps

until the last ruler Mati’el [129].

From this core territory, Bit Agusi expanded; at the peak of its

power its territory extended from the Euphrates in the east to

the Afrin River in the west, and from the Jabbul Lake area in

the south to the Turkish borders in the north.

The history of Bit Agusi is one of constant wars. Since

the first Assyrian incursions west of the Euphrates, this polity

seems to have held a leading postion in the coalitions aginst

Assyria. Moreover, Bit Agusi had a border conflict with Zakkur,

King of Hamath and Lu’ash, that was settled by Adadnirari III

and the Turtan Shamshi-ilu.[130]

It also participated in a coalition of Syrian kingdoms against

Zakkur. [131] The last king of

Bit Agusi, Mati’el, had a particularly aggressive policy: he

fought a war against the king of Kittika[132]

and he allied himself with the King of Urartu against Assyria.

[133] This alliance led his dynasty and his kingdom to

their downfall: in 740 B.C. Tiglath-Pileser III marched against

the capital, Arpad. Destroyed it, and annexed it to the Assyrian

Empire.

Little archaeological evidence is availablr to

complement the history of this kingdom. The main capital

Arpad-Tell Rifa’at was excavated[134]

but only prelimunary reports have been published and these do

not provide insights into the city’s organization and monuments.

Aleppo [135] and ’Ain Dara

[136] have yielded monumental

temples of the 11th century B.C., built

128. Grayson 1991: 218.

129.Lipinski 2000a: 219. Lipinski has adopted the reading

hdrm proposed by Puech (1992) for the inscription of the

Bregh stele instead of ‘brm (Zadok 1997b: 805), and

identifies the Bar-Hadad of the Bregh stele as king of Bit Agusi

and son of Attarsumki I.

130. Grayson 1996: 203.

131. KAl 202.

132. KAl 222-224.

133. Tadmor 1994.

134. Seton Williams 1961 and id. 1967.

135. Kohlmeyer 2000; id. 2009; id. 2012; Gonnella – Khayyata –

Kohlmeyer 2005.

136. Abou-Assaf 1990 and Novak 2012.

probably under the rule of the Luwian dynasty of Palistin but

which continued to be use in the Iron Age II under the rule of

Bit Agusi. Apart from the temple nothing is known about the Iron

Age city of Aleppo and investigations in the lower city of ’Ain

Dara have been limited.[137] No

other substantial information relevant to the history of Bit

Agusi is available from the excatated sites.

4.4 Bit Gabbari-Yadiya

The Aramaen kingdom of Yadiya, which was founded by Gabbar, is

mentioned for the first time in the inscriptions of Shalmaneser

III for the year 858 B.C. It is located on the eastern slope of

the Amanus Mountain and was founded as early as the late 10th

century B.C. The northern location of this Aramaen kingdom seems

to indicate that the settlement area of Semitic-speaking

Aramaeans was not confined to northeast Syria but that these

groups were also present at the northern edge of Syrian

territory. The history of the kingdom of Yadiya is well

documented by the Assyian annals and by local Phoenician and

Aramaic inscriptions of its rulers[138]

and officials.[139] These

inscriptions allow the reconstruction of its ruling dynasty from

the founder Gabbar to the last ruler Bar-Rakkab, after whose

rule Sa’al became an Assyrian province.[140]

Severe crises threatened both the ruling dynasty and the

polity during its two-century-long existence. This complex and

insecure situation was created on the one hand by the mixed

Aramaen and Luwian population,which co-existed with difficulty,

and on the other by the fact that the Aramaean kingdom of Yadiya

wes perceived as an alien body by its threatening Neo-Hittite

neighbors. The troubled internal situation and the external

threats are clearly reflected in the 9th-century B.C. royal

inscription of Kulamuwa (KAI24). This situation led the rulers

of this Aramaean kingdom to seek Assyrian protection very early,

enabling them to develop and to prosper in spite of their

precarious situation.

The wealth of Sam’al is clearly reflected in the archaeological

evidence, which has unveiled strongly fortified lower and upper

cities and a series

137. Zimansky 2002.

138. KAI 24 and 214-221.

139. Schloen – Fink 2009a; iid. 2009b; iid. 2009c.

140. Lipinski 2000a: 247.

of beautifully decorated hilani. Sam’al must have been

incorporated into the Assyrian provincal system before 681 B.C.,

since a governor of Sam’al appears in the eponym list for that

year. of beautifully decorated hilani.

[142]

The University of Chicago’s new excavations[143]

investigating both the upper and the lower cities will certainly

enhance our understandingo of this kingdom’s history by

providing new archaeological and textual evidence such as the

recently found inscription of Kuttamuwa. an official of the

8th-century B.C. King Panamuwa II.[144]

The new archaeological investogation of the site of Zincirli,

ancient Sam’al, also promises to yoeld substantial evidence for

the study of Aramaean and Luwian relations and the impact these

two cultures had on each other. It will also allow for a better

understandingo f the process that led to the formation of an

Aramaean polity in such a hostile enviroment.

4.5 Hamath---Lu’ash

The Aramaean kingdom of Hamath and Lu’as’ in the 9th century

B.C. was ruled by a Luwian dynasty that controlled only the land

of Hamath. Three o fits kings, Parata, Urhilina, and his son

Uratami, are known from both the Assyrian annals of Shalmaneser

III [145]and the local Luwian

inscriptions that were found scattered on Hamath’s territory.

[146] In these inscriotions the kings are called ”Hamathite.”

At the begining of the 8th century and under hazy

circumstances, an Aramaean leader called Zakkur[147]

founded a new dynasty, added a northern territory called Lu’as’

to the conquered kingdom of Hamath, and built a new capital

called Hazrak. It was perhaps this usurpation that led other

Aramaean and Luwian kingdoms to form a coalition against him as

echoed in the stele he erected to commemorate his victory over

them. [148]In 738 B.C.

Tiglath-Pileser III[149]

incorporated 19 districts of his kingdom into the Assyrian

Empire and formed the provinces of Summer and Hattarika.

[150]

141. Von Luschan 1893; id. 1898; id. 1902; id. 1911; id. 1943.

142. Millard 1994:102f.

143. Schloen – Fink 2009a; iid. 2009b; iid. 2009c.

144. On the inscription, cf. Pardee 2009a; id. 2009b; Masson

2010; Nebe 2010; Lemaire 2012; id. 2013.

145. Grayson 1996: 23.

146. Hawkins 2000: 398-423.

147. Lipinski 2000a: 301 suggests that he was from ‘Ana on the

Euphrates.

148. KAl 202.

149. Ann 19, 9-10 and 88-89, Ann 26, 5; cf. Tadmor 1994:62f.

150. Lipinski 2000a: 315 and Radner 2006-2008a: 58 n. 50; 62 n.

60.

The rest of the kingdom was annexed by Sargon II, who conquered

the capital Qarqar in 720 B.C. [151]

Old and recent excavations on the site of Hamath,

[152] Tell Qarqr, [153] Tell ’afis, [154] Tell Mastuma,

[155] and Tell Mishrife[156]

have yielded new and interesting evidence on the cities and

villages of this kingdom. As we have seen, Tell Afis, commonly

identified with the newly founded capital Hazrak,

[157] and Tell Qarqur, also commonly identified with the

old capital Qarqar, [158]have

greatly contributed to the understandingo f the transition

period between the Late Bronze and Iron ages. It is to be hoped

that future excavations at both sities will reveal more insights

into their history and the daily life of their inhabitants.

Recent excavations at Tell Mishrifeh, Bronze Age Qatna,

have revealed a huge and compex city of the Iron Age II.

[159] The archaeological evidence, which includes a

palace, industrial zones, and warehouses, suggests that the site

was a major city of the territory of Hamath in the Iron Age II.

The existence of rural settlements scattered around the tell

strengthens the assumption that Mishrifeh was a main regional

and political center of the kingdom of Hamath, the capital of

the ”districts” of the kingdom. It represents a very good

example of the adminstrative system in use in the kingdom during

the Iron Age.

Tell Mastuma is in turn a very good example of a

well-planned Aramaean rural settlement, displaying an

arrangement composed of repetitious blocks of domestic building,

which betrays a social structure based on large family groups

and has yielded invaluable information about the town planning,

architecture, and econimy of a typical Aramaean rural site.

4.6 Aram-Damascus-Kur

Sa-imerisu

The kingdom of Damascus is mentioned for the first time in the

annals of Shamaneser III as a major participant in the Aramaean

coalition against the Assyrian king at the battle of Qarqar. The

biblical account, which ascribes the foundation of this kingdom

to Reson, [160] an effort of

Hadad-Eze

151. For a list of the kings of Hamath, see Lipinski 2000a: 318.

152. Riis 1948 and Fugman 1958.

153. Domeman 2000.

154. Mazzoni 1995 and ead. 2005.

155. Iwasaki et al. (eds.) 2009.

156. Morandi Bonacossi 2006 and id. 2007a.

157. Lipinski 2000a: 305 and n. 374.

158. For a recent discussion see Lipinski 2000a: 264f.

159. Morandi Bonacossi 2006 and id. 2007a.

160.) Lipinski 2000a: 368f argues for a reading of Ezron.

of Sobah, is not corroborated by extra-biblical sources. So,

little is known about the origion of this kingdom and its later

history is mainly known from the Assyrian records and the Binle.

The lacunal state of the Tell Dan inscription does not allow for

decisive historical conclusions. The fact that Tiglath-Pileser

III calls the kingdom bit haza’ili

[161] may lead to the

assumption that the key figure in the history of this Aranaean

polity was Hazael, [162] a

usurper and the 9th-century founder of the dunasty that ruled

until the Assyrian conquest. A long list of rulers

[163] can be reconstructed on the

basis of the above-mentioned sources but only the rule of the

9th-and 8th-century kings is historically verified. The kingdom

was repeatedly attacked by the Assyrians untill it was finally

annexed by Tiglath Pileser III in 732 B.C.

The Bible insists on the armed conflicts that opposed

the Israelites and the Aramaens of Damascus and it conceals

almost any postive aspects in these relations.

[164] Territorial claims and the control of the trade

routes that linked the arabian peninsula (King’s Highway) and

the Medierranean to north Syria appear to be behind the lating

Israelo-Aramaean conflicts. [165]

After the creation of the kingdoms of Isreal and Judah,

a longlasting coalition seems to have been established between

the Aramaens kingdom of Isreal.

It is quite surprising that the territory of the

kingdom of Adam-Damascus has been hardly touched by

archaeological investigation to date. The only survey,

undertaken by F. Braemer, [166]

yields no information about the Iron Age settlement and no

large-scale excavations have revealed extensive Iron Age

remains. As for the capital, Damascus, the ancient settlement is

most probably hidden under the modern old twon.

[167] The discovery of an orthostat representing a

ashinx[168] that was found

re-used in a Hellenistic wall under the Omayyad mosque may hint

at the location of the Iron Age Hadad temple in that same area.

There is a pressing need for new archaeological investigation of

this kingdom’s territory in order to gain more insights into its

history and into its relations with its neighbors.

161. Tadmor 1994:138,186.

162. For Hazael, cf. Niehr 2011.

163. 3 Lipinski 2000a: 407.

164. For these relations, see Kraeling 1918; Reinhold 1989;

Axskjöld 1998; Hafporrson 2006.

165. 5 Pitard 1987:94f, 109.

166. Braemerl984.

167. Cf. Sack 1989:7-4 and ead. 1997:386-391.

168. Abd-el-Kader 1949:191 and pls. 7 and 8; Trokay 1986; Caubet

1993.

5. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The Aramaeans of ancient Syria were the descendants of the Late

Bronze Age Population of Syria in all its diversity and the

heirs of its culture. The main lines of their formation process

can be evidence. The new communities---among which predominated

West Semitic-speaking groups---that emerged as a result of the

collapse of the Late Bronze age urban system were composed of

people from whithin and without the cities. These communities

were founded according to new principles of domestic autonomy

and d equality between kin-based groups.

[169]The allegiance of the people in This Kin-related

society, relying mainly on agriculture and cattle breeding,

belonged to the group. However, with the regeneration of complex

societies this allegiance was trasferred to the polity and to

the representative o fits identity and power: the ruling dynast

who was the descendant of the leader of the founding house.

The Aramaean polities of the Iron Age like those of

the Late Bronze Age were never united in one kingdom and never

shared a feeling of ”national” belonging. Their external

relations were dicated by the strategic interests of their

kingdoms and not by any other consideration. The Assyrian threat

prompted alliances with polities of different linguisic and

cultural backgrounds: Luwians, phoenians, Israelites, and even

Urataeans. We find no instance of Aramaeans uniting together to

fight against non-Aramaeans. The solidarity against a common

enemy, mainly Assyrian, did not prevent the Aramaean kingdoms

from turning against each other for economic reasons and/or

territorial claims.

Syria in the Iron Age was a mosaic of kingdoms and

different ethnolinguistic groups but it is the language of the

Semitic-speaking population that became the markr of this new

era. The Assyrian might have inflicted a military and poltical

defeat on the Aramaeans of Semitic-speaking population that

became the marker of this new era. The Assyrian might have

inflicted a military and political defeat on the Aramaeans of

Syria but the victory of the latter was a long-lasting cultural

one: their language became the lingua france of the

Ancient Near East for several centuries and survives today.

169. Routledge 2004. |