|

The Tel Dan Stela and the

Kings of Aram and Israel

Non-Technical - maj 04, 2011 - by

Bryant G. Wood PhD

Share/recommend this article:

Excerpt

A people known as the Arameans lived in the

regions of Syria and Mesopotamia in

antiquity. They were a large group of

linguistically related peoples who spoke

dialects of a West Semitic language known as

Aramaic. Although not politically unified,

they developed powerful city-states that had

a strong cultural influence in the Near East

in the first millennium BC. The Aramaic

language, very similar to Hebrew, became the

official international language during the

Persian Period, ca. 539–332 BC, and

eventually replaced many of the local

languages of the area, including Hebrew. As

a result, in New Testament times the main

local language was Aramaic rather than

Hebrew.

Continue reading

The nation of Israel was in conflict with

the Arameans for about 300 years, from the

time of David, ca. 1000 BC, until Assyria

annexed the Aramean city-states at the end

of the eighth century BC. Most of the

conflict was with the city-state of Damascus

that, under Hazael, dominated Israel in the

second half of the ninth century. A recently

discovered inscription, the Tel Dan Stela,

takes us back to those days.

Discovery

and Significance of the Tel Dan Stela

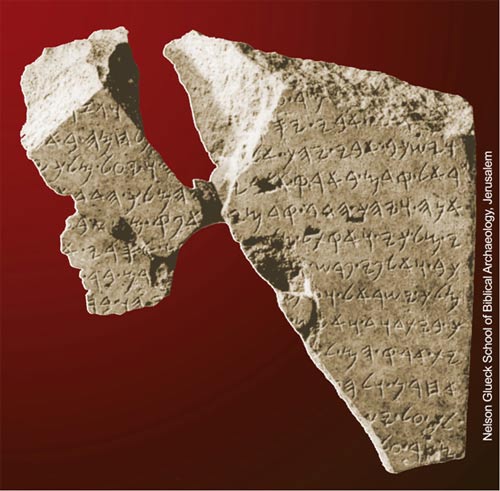

The largest fragment of the Tel Dan Stela,

Fragment A, was discovered at Tel Dan in

northern Israel in July 1993 (Biran and

Naveh 1993; Wood 1993). Then, in June 1994,

two additional joining fragments, labeled

Fragment B, were found (Biran and Naveh

1995). Together, Fragments A and B represent

only a fraction of a much longer

inscription. The language is Aramaic and it

celebrates the victory of a king of Aram

over Israel and Judah. It is the first royal

inscription from the kingdom period to be

found in Israel.

Tel Dan Inscription, the first royal

inscription from the kingdom period to be

found in Israel. Fragment A (right) was

discovered in 1993 and Fragment B (left) was

discovered one year later. Dated to ca. 841

BC, the original inscription named at least

eight Biblical kings.

The most stunning aspect of the document is

the reference to Judah as the “House of

David.” For the first time, it was thought,

the name David appeared in an extra-Biblical

document. At about the same time, however,

two French scholars, André Lemaire (1994)

and Émile Puech (1994), independently

recognized the same phrase in the

Mesha

Inscription,

which has been around for well over 100

years (Wood 1995). It now likely that the

name David is in a third inscription.

Egyptologist K.A. Kitchen believes that the

phrase “highland of David” appears in the

Shishak inscription in the Temple of Amun at

Karnak, Egypt (1997: 39–41). All this at a

time when a number of scholars were

challenging the existence of the United

Monarchy and a king name David!

Unfortunately, the beginning of the Tel Dan

Stela is missing. This is where the name of

the king who commissioned the memorial, and

the event which occasioned it, would have

been recorded. With the discovery of

Fragment B, however, we can assign the

stela’s place in history with near

certainty. Parts of the names of two kings

are preserved in Fragment B: Joram, son of

Ahab, king of Israel from 852 to 841 BC, and

Ahaziah, son of Jehoram, king of Judah (the

House of David) in 841 BC. With this new

information it is possible to assign the

stela to Hazael, king of Aram-Damascus, who

undoubtedly set it up in Dan to commemorate

his victory over Joram and Ahaziah at Ramoth-Gilead

in ca. 841 BC (2 Kgs 8:28–29).

In this article we will consider six kings

associated with the stele: the predecessor

of Hazael, (Ben-Hadad II), Hazael, Joram,

Jehoram, Ahaziah, and Jehu. Because of the

fragmentary nature of the stela, there are

gaps in the lines that allow a number of

interpretations. The translation below is

that of the original publishers of the

inscription, Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh

(1995). The numbers are the line numbers of

the inscription and the sections inside the

brackets are the restored portions.

1. [...] and cut [...]

2. [...] my father went up [against him

when] he fought at [...]

3. And my father lay down, he went to his

[ancestors] and the king of I[s-]

4. rael entered previously in my father’s

land. [And] Hadad made me king.

5. And Hadad went in front of me, [and] I

departed from [the] seven [...-]

6. s of my kingdom, and I slew [seve]nty

kin[gs], who harnessed thou[sands of cha-]

7. riots and thousands of horsemen. [I

killed Jo]ram son of [Ahab]

8. king of Israel, and [I] killed [Ahaz]iahu

son of [Jehoram kin-]

9. g of the House of David. And I set [their

towns into ruins and turned]

10. their land into [desolation ...]

11. other [... and Jehu ru-]

12. led over Is[rael ... and I laid]

13. siege upon [...]

Ivory

carving found at Arslan Tash, Syria. A cache

of ivories found at the Assyrian outpost of

Arslan Tash was undoubtedly booty taken from

Hazael’s palace in Damascus. The regal

figure depicted on this piece is probably

Hazael himself.

(Louvre Museum, Paris) Ivory

carving found at Arslan Tash, Syria. A cache

of ivories found at the Assyrian outpost of

Arslan Tash was undoubtedly booty taken from

Hazael’s palace in Damascus. The regal

figure depicted on this piece is probably

Hazael himself.

(Louvre Museum, Paris)

His Career

Hazael ruled for some 42 years, ca. 842–800

BC, and was the most powerful king of Aram.

He is referred to numerous times in the Old

Testament, as well as in contemporary

Assyrian inscriptions.

The fulfillment of Elisha’s prediction that

Hazael would bring harm to Israel began

shortly after he took the throne. He

defeated the combined armies of Israel and

Judah at Ramoth Gilead, 50 km (30 mi)

southeast of the Sea of Galilee. Hazael’s

boast in lines 9 and 10 that he “set [their

towns into ruins and turned] their land into

[desolation]” most likely refers to his

defeat of Israel and Judah at Ramoth Gilead.

Joram, king of Israel, was wounded in the

battle. Ahaziah, king of Judah, went to

visit Joram at Jezreel. It was at that time

that Jehu assassinated both Joram and

Ahaziah and became next king of the Northern

Kingdom.

In lines 7 and 8 of the stela Hazael takes

credit for the deaths of Joram and Ahaziah.

Whether this was exaggeration, or Jehu

acting as Hazael’s agent, we cannot say. It

is interesting, however, that God commanded

Elijah to anoint Hazael king (1 Kgs 19:15),

a very unusual circumstance. God used Hazael

to accomplish His purposes in the history of

Israel and Judah.

For the next five years, ca. 841–836 BC,

Hazael was taken up with invasions by the

Assyrians, so did not bother Israel.

Shalmaneser III in his 18th year (ca. 841

BC) engaged Hazael at Mt Senir. He bragged

about killing 16,000 Aramean soldiers. He

also captured 1,121 chariots, 470 cavalry

horses, and Hazael’s camp. He besieged

Hazael in Damascus and cut down his gardens

(Oppenheim 1969: 280).

In Shalmaneser III’s 21st year (ca. 838 BC),

he conquered four of Hazael’s larger towns

(Oppenheim 1969: 280). An inscription on a

marble bead from Assur reads,

Booty of the temple of Sheru from the town

of Mallaha, the royal residence of Hazael of

Damascus (Oppenheim 1969: 281).

Two ivories, probably taken as booty by the

Assyrians, are inscribed on the back with a

dedication to “our lord Hazael” (Pitard

1997: 104; Ephal and Naveh 1989: 197).

After 836, Hazael continued his aggression

against Israel and Judah. During the reign

of Jehu (ca. 841–814 BC) he captured all of

the Israelite territory east of the Jordan

River (2 Kgs 10:32–33). In the 23rd year of

Joash, son of Ahaziah (2 Kgs 12:6, ca.

815–814 BC), Hazael captured Gath and

attacked Jerusalem (2 Kgs 12:17). Joash was

able to pay him off and save the royal city:

But Joash king of Judah took all the sacred

objects dedicated by his

fathers—Jehoshaphat, Jehoram and Ahaziah,

the kings of Judah—and the gifts he himself

had dedicated and all the gold found in the

treasuries of the temple of the Lord and of

the royal palace, and he sent them to Hazael

king of Aram, who then withdrew from

Jerusalem (2 Kgs 12:18).

Hazael was no doubt replenishing his coffers

following the raids by the Assyrians. Jehu’s

son Jehoahaz (ca. 814–798 BC) “did evil in

the eyes of the Lord” (2 Kgs 13:2). As a

result,

the Lord’s anger burned against Israel, and

for a long time He kept them under the power

of Hazael king of Aram and Ben-Hadad [III]

his son (2 Kgs 13:3; cf. 13:22).

The war against Hazael took its toll on

Israel’s army. It was reduced to 10,000

soldiers, 50 horsemen, and ten chariots (2

Kgs 13:7a). “The king of Aram had destroyed

the rest and made them like the dust at

threshing time” (2 Kgs 13:7b). Relief came

from the Lord, who “provided a deliverer for

Israel, and they escaped from the power of

Aram” (2 Kgs 13:5; cf. 13:23).

This deliverer was most likely the Assyrian

king Adadnirari III (ca. 810–783 BC), who

attacked Damascus in 806 (Oppenheim 1969:

281–82). Hazael died sometime around the

time Jehoash, son of Jehoahaz, took the

throne (ca. 798 BC, 2 Kgs 13:24).

Ivory carvings of winged figures found at

Arslan Tash, Syria. Scholars believe they

came from Hazael’s palace in Damascus and

were brought to Arslan Tash as booty.

(Louvre Museum, Paris; photo by Michael

Luddeni)

Ahab, King of Israel

(ca. 874–853 BC)

Ahab’s name originally appeared on the stela

since Joram, his son, is listed in typical

Near Eastern fashion as [...Jo]ram son of

[...] in line 7. Ahab’s name, however, is

missing since it was on a portion of the

stela that did not survive. We have dealt

with Ahab in an earlier article in this

series (Wood 1996a), so we will not repeat

that information here, but move on to his

son Joram.

Joram, King of Israel (ca. 852-841 BC)

Following Ahab’s death, his son Ahaziah

ruled for two years, 853–852 BC. He died in

an accidental fall in the palace and left no

son, so his brother Joram became next king

of Israel (2 Kgs 1:2–17). The mention of

Joram in the Tel Dan Stela is the first

reference to this king outside the Bible.

Joram reigned for 12 years (2 Kgs 3:1).

Although he did evil in the eyes of the

Lord, he was not as bad as his father Ahab

and his mother Jezebel. The outstanding

event of his reign seems to be the removal

of the sacred stone of Baal that Ahab had

made (2 Kgs 3:2).

Joram was on good terms with the kings of

Judah. He teamed up with Jehoshaphat to put

down a revolt of Mesha, king of Moab, in ca.

846 BC (2 Kgs 3:4–27; Wood 1996b: 55–58).

The next king of Judah, Jehoram (848–841

BC), married Joram’s sister Athaliah (2 Kgs

8:18, 26). Her son Ahaziah became king of

Judah following Jehoram. In 841 BC Joram

joined forces with his nephew Ahaziah to

fight against Hazael at Ramoth Gilead. He

was wounded and went to Jezreel to recover

(2 Kgs 8:28–29).

Following his anointing by Elisha, Jehu went

to Jezreel to assassinate Joram. He shot him

in the back with an arrow as Joram was

fleeing (2 Kgs 9:14–24). Jehu ordered

Joram’s body to be thrown on the field of

Naboth to fulfill a prophecy he heard after

Naboth was murdered by Joram’s mother

Jezebel (2 Kgs 9:25–26).

Jehoram, King of Judah (ca. 848—841 BC)

Jehoram was originally named in the Tel Dan

Stela since Ahaziah’s father’s name was

given. However, the section of the stela

where his name appeared is missing. Jehoram

became king when he was 32 years old and

ruled for 8 years. He was one of the more

wicked kings of Judah.

When Jehoram became ruler, he killed all of

his brothers and other contenders for the

throne (2 Chr 21:4). He married Athaliah,

daughter of Ahab, and built high places on

the hills of Judah (2 Chr 21:6, 11). During

his reign the Edomites revolted. While

attempting to subdue them, Jehoram and his

commanders were surrounded. Fortunately, he

was able to break through at night and

escape to Jerusalem (2 Kgs 8:20–22).

Because of his wicked ways, Elijah the

prophet wrote Jehoram a condemning letter.

He told the king,

The Lord is about to strike your people,

your sons, your wives, and everything that

is yours, with a heavy blow (2 Chr 21:14).

Soon after, a coalition of Philistines and

Arabs overran the palace and carried off all

the goods of the palace, the king’s sons,

with the exception of Ahaziah the youngest,

and his wives.

Elijah also told Jehoram in the letter that

he would be smitten with a disease of the

bowels (2 Chr 21:15). After the palace was

ransacked Jehoram became ill with an

incurable disease of the bowels that lasted

two years (2 Chr 21:18–19a). Although he was

buried in the City of David, no fire was

made in his honor and he was not buried in

the tombs of the kings (2 Chr 21:19b–20).

Ahaziah,

King of the House of David (ca. 841 BC)

As with Jehoram, the mention of Ahaziah in

the Tel Dan Stela is the only reference we

have to this king outside the Bible. Ahaziah

came to the throne at the tender age of 22

and ruled for only one year. He was the

youngest son of Jehoram, the previous king

of Judah. The other sons had been carried

off by the Philistines and Arabs (2 Chr

21:16–17).

Ahaziah followed the ways of his Israelite

mother Athaliah and “did evil in the eyes of

the Lord” (2 Chr 22:4a). The members of the

family of Ahab his grandfather became his

advisors (2 Chr 21:4b). They urged him to

join Joram in his fight against Hazael at

Ramoth Gilead which resulted in his

premature death (2 Chr 21:5).

While Joram was in Jezreel recovering from

the wound he received at Ramoth Gilead,

Ahaziah went to visit him. He was in the

company of Joram when Jehu struck him down.

Ahaziah fled, but was caught and put to

death by Jehu and his men (2 Kgs 9:27; 2 Chr

22:6–9). His body was brought back to

Jerusalem and he was buried “with his

fathers in his tomb in the city of David” (2

Kgs 9:28).

Jehu,

King of Israel (841—814 BC)

Jehu is another name that was on a portion

of the stela that is missing. The end of

line 11 and the beginning of line 12 refers

to another king of Israel following Joram:

“[X ru]led over Is[rael].” Since Jehu was

the next king of Israel following Joram, it

stands to reason that his name appeared

here.

Jehu led a bloody purge of the royal

families of both Israel and Judah. Following

the assassination of Joram and Ahaziah (2

Kgs 9:24–27), he murdered the family and

officials of Ahab (2 Kgs 9:30–33; 10:11, 17)

and 42 of the royal family of Judah (2 Kgs

10:14). The purge did not end there. He

brought all the “prophets of Baal, all his

ministers and all his priests” (2 Kgs 10:19)

into the temple of Baal in Samaria and had

them executed (2 Kgs 10:25). This

effectively ended Baal worship in Israel.

But it did not end idolatry, for Jehu

continued “the worship of the golden calves

at Bethel and Dan” (2 Kgs 10:29).

During Jehu’s reign Israel lost territory

east of the Jordan to Hazael (2 Kgs

10:32–33). Jehu was also subject to Assyria

as attested by the Obelisk of Shalmaneser,

or the Black Obelisk as it is sometimes

called. This monument was discovered by

Englishman Sir Henry Layard in Calah, Iraq,

in 1846. It depicts Jehu prostrate before

the Assyrian king Shalmaneser, with

Israelite emissaries bearing tribute behind

him. (The

picture of Jehu can be seen in this article).

The inscription reads,

The tribute of Jehu, son of Omri; I

received from him silver, gold, a golden

saplu bowl, a golden vase with pointed

bottom, golden tumblers, golden buckets,

tin, a staff for a king, (and) wooden

puruhtu (Oppenheim 1969: 281).

This is the only surviving likeness of a

king of Israel or Judah. After ruling for 28

years, “Jehu rested with his fathers and was

buried in Samaria” (2 Kgs 10:35).

The Tel Dan Stela is extraordinary in that

it names eight Biblical kings: Ben-Hadad II,

Hazael, Joram, Ahab, Ahaziah, Jehoram, David

and Jehu. It was most likely erected

following Hazael’s defeat of Joram and

Ahaziah at Ramoth Gilead in ca. 841 BC (2

Kgs 8:28–29). The occasion for the breaking

of the stela was probably when Jehoash, king

of Israel from 798 to 782, recaptured

Israelite territory previously taken by

Hazael (2 Kgs 13:24–25). It appears that the

monument stood in Dan near the city gate for

over four decades. It was a constant

reminder to the Israelites that they were

subject to the Arameans. When the tide of

political power shifted, the Israelites

gained the upper hand and the hated stela

was broken into many pieces, some of which

were reused as building material.

The importance of the Tel Dan Stela lies

not in its record of history, because the

Bible gives a much fuller account. Its

importance, rather, lies in the fact that it

is an independent, contemporary, witness to

the events of ca. 841 BC and the accuracy of

the Biblical record.

Bibliography

Biran, A., and Naveh, J.

1993 An Aramaic Stele Fragment

from Tel Dan. Israel Exploration Journal

43: 81–98.

1995 The Tel Dan Inscription: A

New Fragment. Israel Exploration Journal

45: 1–18.

Eph’al, I., and Naveh, J.

1989 Hazael’s Booty

Inscriptions. Israel Exploration Journal

39: 192–200.

Kitchen, K.A.

1997 A Possible Mention of

David in the Late Tenth Century BCE, and

Deity *Dod as Dead as the Dodo? Journal

for the Study of the Old Testament 76:

29–44.

Lemaire, A.

1994 “House of David” Restored

in Moabite Inscription. Biblical

Archaeology Review 20.3:30–37.

Oppenheim, A.L.

1969 Babylonian and Assyrian

Historical Texts. Pp. 265–317 in Ancient

Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old

Testament, 3rd ed., ed. J.B. Pritchard.

Princeton NJ: Princeton University.

Pitard, W.T.

1997 Damascus. Pp. 103–106 in

The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in

the Near East 2, ed. E.M. Myers. New

York: Oxford University.

Puech, É.

1994 La stèle de Dan: Bar Hadad

II et la coalition des Omrides et de la

maison de David. Revue Biblique 101:

215–41.

Wood, Bryant G.

1993 New Inscription Mentions

House of David.

Bible and Spade

6: 119–21.

1995 House of David Again!

Bible and Spade

8: 91–92.

1996a

Ahab

the Israelite.

Bible and Spade 9: 111–113.

1996b

Mesha,

King of Moab.

Bible and Spade 9: 55–64.

2011-05-19 12:10

Perhaps the most thorough study of Hazael to

date is:

Younger, K. Lawson, Jr.

2005 “‘Haza'el, Son of a Nobody’:

Some Reflections in Light of Recent Study.”

Pp. 245-270 in Writing and Ancient Near

Eastern Society: Papers in Honour of Alan R.

Millard. Ed. P. Bienkowski, C. Mee, and E.

Slater. New York: T&T Clark.

A.D. Riddle - 2011-05-19 12:10:01

2012-03-02 21:00

The Tel Dan Stela is not the first royal

inscription to be found in Israel (that

would be Seti I's Beth-Shean stelae,

although I might be mistaken).

E.

Harding

- 2012-03-02 21:00:55

2012-03-07 16:45 Yes, Mr. Harding is quite

right. Since the Seti I stelae (actually,

there were two) are from the Judges period,

we could say that the Tel Dan Stela is the

first royal inscription to be found in

Israel from the kingdom period. We have made

this correction to the article. We do have,

however, three fragments of an Assyrian

inscription found at Ashdod, probably of

Sargon II or his general (Isaiah 20:1), but

unfortunately no names have survived on the

three fragments. In addition, a fragment of

a stela was found at Megiddo with the

cartouches of Shishak (1 Kings 11:40,

14:25–26; 2 Chr. 12:1–11), but no text was

preserved.

Dr. Bryant Wood

http://www.biblearchaeology.org/post/2011/05/04/The-Tel-Dan-Stela-and-the-Kings-of-Aram-and-Israel.aspx |