|

THE ARAMAEANS

A.Malamat

In the last quarter of the second millennium

B.C. a west-Semitic people, speaking various

Aramaic dialects, spread out from the

fringes of the Syro-Arabian desert (though

it is sometimes held that they came from the

north), fanning out over the Fertile

Crescent, from the Persian Gulf to the

Amanus mountains, the Lebanon, and

Transjordan. This burgeoning forth –

unparalleled in the ancient Near East - was

held in check by the great powers of the

day, till their decline let it loose over

the civilized regions of Hither Asia.

Originally nomadic or semi-nomadic, the

Arameans rapidly became an important

political and economic factor. Though their

earliest historical appearance remains

controversial, the Bible notes the kinship

of these Arameans with the Hebrew

Patriarchs, and records a vital, 300-year

relationship, both friendly and hostile,

between the two peoples in later times. In

the course of time the Aramaic language

became thoroughly entrenched in Hebrew

culture; it was the language of parts of the

Bible (in the books of Ezra and Daniel) and

remained in everyday use among Jews for over

a millennium.

(i) History

Aram is mentioned as a place-name as early

as the twenty-third century B.C., in an

inscription of Naram-Sin of Akkad, which

refers to a region on the Upper Euphrates,

and in c. 2000 B.C. in documents from Drehem,

as a city on the Lower Tigris. It occurs as

a personal name in the latter documents, in

the Mari texts (eighteenth century B.C.), at

Alalah (seventeenth century), and at Ugarit

(fourteenth century). One of the Ugaritic

texts mentions the ‘fields of Aram(aeans)`,

though its ethnic character here is

doubtful.[1] Aram is also mentioned in

Egyptian sources, as a place-name (ps-irm)

in Syria, in a recently discovered

topographical list of Amenophis III (first

half of the fourteenth century B.C.);[2] and

again in an Egyptian frontier journal from

the time of Merenptah, about 1220 B.C. (thus

the name should

not be emended, as is often done, to

Amurru). Yet these isolated references are

inconclusive in establishing such an early

appearance of the Arameans, especially since

the name Aram is later frequent as an

onomastic and toponymic element even in

entirely un-Aramean contexts.

The earliest definite extra-biblical

reference to the Arameans is from the time

of Tiglath-pileser I of Assyria (1116-1076

B.C.) This king’s consistent reference to

the compound name Ahlame-Ar(a)maya in his

inscriptions has led to the consideration

that the Ahlamu were actually Arameans, and

that the latters first appearance thus

stemmed back to the early attestation of the

Ahlamu near the Persian Gulf at the

beginning of the fourteenth century B.C.[3]

This identification, however, is untenable,

for the Aramaeans are mentioned quite

separately from, and alongside, the Ahlamu

(and the Sutu) in an inscription most likely

attributable to Ashur-bel-kala

(Tiglath-pileser I`s successor),[4] while

the Assyrian kings Adad-nirari II and

Ashur-nasir-apli II (tenth-ninth centuries

B.C.) refer to the Ahlame-Armaya alongside

the Aramaeans per se.

The compound Ahlame-Armaya rather denotes an

association of nomadic groups, in analogy

with similar couplings of tribal names, such

as the Old Babylonian references to

Amnanu-Yahrurum, Hana-DUMU.MESH-Yamina,

Amurru-Sutium.[5] One such component name

may well have come semantically to denote

the generic concept ‘nomad’ as probably

happened with the names Ahlamu and Sutu.

Moreover, the term Aram displays a

particular tendency for coupling, as in the

biblical Aram-Naharaim, Aram-Zobah,

Aram-Damascus, Aram-Beth-Rehob, and Aram-Maacah.

At any rate, the close historical

relationship of the Ahlamu and the Aramaeans

led occasionally in late cuneiform sources

to the Aramaic language and script being

referred to as ‘Ahlamu’.[6] Tiglath-pileser

I’s inscriptions deal with the Aramaeans in

two separate contexts: in the Annals for his

fourth year (1112 B.C.) he boasts that he

'went forth into the desert [here the

west-Semitic term mudbara is

employed], into the midst of the

Ahlame-Armaya.

. . . The country from Suhu [on the Middle

Euphrates--biblical

Shuah, Gen. 25: 2] to the city of Carchemish

I raided in one day’

(A.R.A.B. i, § 230). Crossing the Euphrates,

he sacked six Aramaean I

villages in the Mount Bishri

district--Mentioned in documents as much as

a millennium earlier as a perennial breeding

ground for nomadic tribes. This is taken as

a clear indication that the Aramaeans had

already become settled in the area

south-east of the great bend of the river,

whence they subsequently spread. The other

reference to the Aramaeans underlines their

stead- fast resistance to the Assyrians:

Tiglath-pileser I relates that, in the

course of repeated campaigns to subdue the

Aramaeans in the west, he had to cross the

Euphrates no less than twenty-eight times.

‘From the foot of the Lebanon mountains,[7]

from the town of Tadmar [biblical Tadmor,

later Palmyra] of the country of Amurru,

[towards] Anat of the country of Suhu, as

far as the town of Rapiqu of the country of

Karduniash [Babylonia], I defeated them`

(cf. A.R.A.B. i, § 287). Here the Aramaean

tribes are already associated with Mount

Lebanon--three or four generations prior to

their entanglement there with Saul and

David. An Assyrian chronicle clearly

testifies to the extreme danger posed by the

Aramaeans towards the end of

Tiglath-pileser’s reign, when they

penetrated even into Assyria proper, seizing

cities and disrupting communications.[8]

Tiglath-pileser’s son, Ashur-bel-kala

(1073--1056 B.C.), mentions the Aramaeans

(unassociated with the Ahlamu) in his Annals

and related documents, referring

specifically (in c. 1070 B.C.) to the ‘land

of Aram` (mat Arime, a genitival form

of the nominative Arumu, Aramu,

affected by vowel harmony), the exact

location of which it is difficult to fix. lf

the so-called ‘Broken Obelisk’ from Nineveh

is actually to be attributed to

Ashur-bel-kala, as seem reasonable then the

Aramaeans (who figure most prominently in

it) were spread over the vicinity of the

Kashiari mountains (modern Tur-'Abdin)

towards the Tigris, in the north, and along

the Habur valley, to the south. In this

period, an Aramaean usurper (a ˜son of a

nobody') bearing the Babylonian name

Adad-apla-iddin even managed to seize the

throne of Babylon."[10] The Aramaeans thus

came to achieve historical significance at

the end of the second millennium and the

beginning of the first millennium B.C., at

which time a cluster of independent Aramaean

states arose.[11] Those in Syria (to which

we shall return below) are known from the

combined evidence of Assyrian, Aramaean, and

biblical sources; those in Mesopotamia

almost entirely from Assyrian documents,

beginning in the late tenth century B.C.

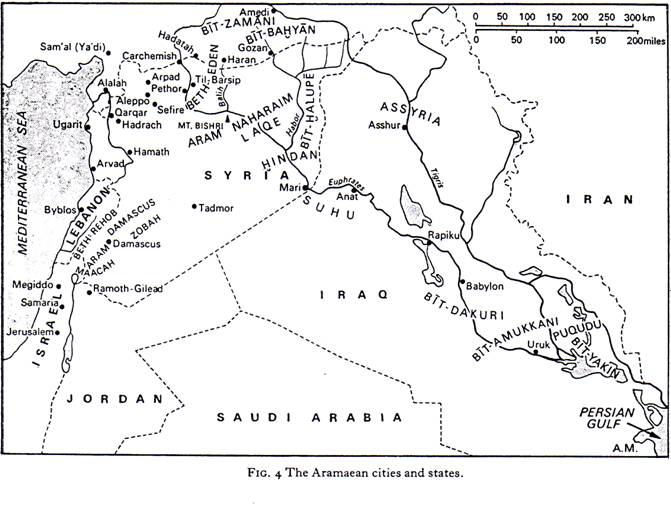

The most important among the latter were

Bit-Adini (biblica Beth Eden; Amos 1:5)

above the great bend of the Euphrates, on

both banks (capital: Til-Barsip); Bit-Bahyan

(capital: Gozan; cf. 2 Kings 17: 6) on the

Upper Habur, and Bit-Halupe on the Lower

Habur; Laqe, Hindan, and Suhu on the Middle

Euphrates; Bit-Zamani in the Kashiari

mountains to the north (capital: Amedi,

modern Diarbekir); and Bit-Amukkani,

Bit-Dakuri, and Bit-Yakin, near the Persian

Gulf. Only a cursory outline of the later

fortunes of the Aramaeans is possible here,

though two of their major states, which rose

in the west and became fatefully entangled

with the Israelites, will occupy us later.

The climax of the Aramaean threat to Assyria

came during the century spanning the turn of

the millennium, when Assyria reached a nadir

under Ashur-rabi II (1012-972 12.C.) and

Tiglath-pileser II (966-935 Bc). Aramaean

power in the west now became severely

curtailed, however, on account of the rising

kingdom of Israel (see below), which

relieved Assyria somewhat on its western

flank. Indeed, towards the end of the tenth

century B.C. Ashur-dan II (934-912 B.C.) was

able to repel the Aramaean states on the

Upper Habur, and Adad-nirari II (911-891

1:.C.) had success there and also on the

Middle Euphrates. Ashur-nasir-apli II

(883-859 B.C.) and, in particular,

Shalmaneser III (858-824 B.C.) dealt the

Aramaeans further blows. Apart from their

renewed campaigns in northern Mesopotamia,

the Assyrians overran the Aramaean states

between the Habur and the Euphrates, and

after successive attempts even the stubborn

kingdom of Bit-Adini fell (in 855 BC), thus

removing the last major stumbling-block

towards the west into Syria. This brought

Shalmaneser III, and later Adad-nirari III

(810-783 B.C.), into a direct confrontation

with the powerful kingdom of Aram-Damascus,

resulting in its subjugation (see below).

Yet the final blow came from Tiglath-pileser

III (744-727 nc.), who reduced the Aramaean

states in Syria to mere Assyrian provinces,

such as Sama’al, Arpad, and Hadrach (cf.

Zech. 9: 1) in the north, and Aram-Damascus

in the south.

In spite of occasional revolts (see below),

the Assyrians held tightly on to Syria, thus

terminating independent Aramaean history in

the west: around the second half of the

eighth century BC. the focus of Aramaean

history shifts to Babylonia. Since the

eleventh century B.C, various Aramaean and

closely related tribes (such as the Suteans

and the ethnically mixed Chaldeans) had

infiltrated in increasing numbers into

Babylonia, rising to play a prominent role

in the days of Tiglath-pileser III.[12] His

inscriptions attest to heavy Aramaean

settlement around the Persian Gulf, and

specify some thirty-five different tribes

”among whom are the Puqudu (the Pekod of

Jer. 50: 21 and Ezek. 23: 23). These tribes,

whose chieftains were frequently designated

by the term nasiku (cf. the Hebrew

cognate nasik, applied to the

Midianite tribal leaders), were a bane to

Tiglath-pileser lll and the succeeding

Sargonid dynasty. They were subjugated only

after repeated attempts, and then exiled in

large numbers (e.g. 208,000 by Sennacherib

in 703 B.C.). Even so, the Aramaeans

ultimately came to the fore as a dominant

factor within the neo-Babylonian empire.

(ii) Origins and Affinities in Biblical

Tradition

An obscure tradition preserved in Amos 9:7

traces the origin of the Aramaeans to a

place called Kir, possibly near Elam (cf.

Isa.22: 6), though Amos 1: 5 and 2 Kings 16:

9 give this as the place to which the

Aramaeans of Damascus were destined to be

exiled. The passages in Amos imply that,

after almost half a millennium of Aramaean

settlement in Syria, there still circulated

a national account of the Aramaean

migration, much like the chronicle of the

Israelitc exodus from Egypt or that of the

Philistines from Caphtor.[13] They further

point to the historical consequences of

Aramaean `misbehaviour’, leading to their

return to their ancestral

homeland--reminiscent of the threat to a

disobedient Israel of being sent back to

Egypt (cf. Deut. 28: 68; Hos. 8: 13).

In the Table of Nations (Gen. 10: 22-23),

the eponymous ancestor Aram, on a par with

Elam and Ashur, is descended directly from

Shem, reflecting the Aramaeans’ rise to

importance in the Near East in the first

third of the first millennium B.C.

Four ‘sons’ (‘brothers’ in the parallel

version in 1 Chr. 1 : 17) are assigned to

Aram: Uz, Hul, Gether, and Mash (LXX and

Chronicles: Meshech; Samaritan Pent. Massa),

whose identity and location are uncertain.

The Qumran War Scroll (Il. 10,

rendering Massa, and Togar instead of

Gether) places these ‘beyond the Euphrates’.

The previously modest standing of the

Aramaeans is reflected in the genealogical

table of the Nahorites (Gen. 22: 20-24),

where Aram is made a grandson of Nahor and

son of Kemuel (whose significance eludes us)

through the lineage of Nahors wife and not

his concubine, thus placing them in

Mesopotamia, not southern Syria.[14] Here,

too, Aram is merely a ‘nephew’, rather than

the ‘father’ of Uz. The Bible closely links

the Hebrew Patriarchs with the Aramaeans:

not only is Abraham a brother of Nahor, but

Isaac and Jacob marry daughters of their

cousins Bethuel ˜the Aramaean and Laban ‘the

Aramaean`, respectively (Gen. 25: 20; 31:

20). It is thus that the narrator attributes

to Laban the Aramaic equivalent for the

Hebrew word gal'ed: yegar sahaduta

˜the stone-heap of witness” (Gen. 31: 47),

an etiology for the place name Gilead. [15]

In one instance a Patriarch himself

(apparently Jacob) is designated as

Arammi ‘obed ˜a roving Aramaean` (Deut.

26; 5; for a similar expression in Assyrian

inscriptions see p. 140 and n. 40).[16] This

tradition conforms with the later Hebrew

names for the ancestral habitat of the

Patriarchs, the district of Harran:

˜Paddan-Aram' (Gen. 25: 20, etc.; Akkadian

paddan, denoting a ‘road’), the field

of Aram (sede Aram; Hos. 12:

12) or 'Aram-Naharaim’, i.e.mainly the

Jezireh`, the Habur, and both banks of the

Euphrates, further west.

As noted above, the appearance of the

Aramaeans in the Patriarchal period is not

confirmed in extra-biblical sources, at

least not as an element important enough to

warrant naming the entire Jezireh after

them. Indeed, epigraphic sources of the

fifteenth-twelfth centuries B.C. refer

simply to Naharaim (Egyptian Naharin(a);

Akkadian Nahrima/Narima), but never to Aram-Naharaim.[17]

Thus the latter appellation, as well as the

alleged Aramaean affinity of the Patriarchs,

appear to be anachronistic concepts,

introduced under the influence of the later

entrenchment of the Aramaean tribes in the

Jezireh region (end of the second millennium

B.C.).[18] The various arguments,

particularly the linguistic ones, put

forward to prove that the Patriarchs were

‘proto-Aramaeans’ have justly been

rejected."[19] That Aram or Aram-Naharaim

was the country of origin of

Cushan-Rishathaim, the first oppressor of

Israel in the period of the Judges (Jud. 3:

8, 11; to be dated c. 1200 B.C.), or of the

still earlier Balaam (Num. 23: 7; Deut. 23:

4), seems also to be anachronistic. As for

Balaam, whose ancestral home was Pethor

(some 20 km. south of Carchemish, on the

western bank of the Euphrates), the

anachronism here may well have come about in

the tenth or first half of the ninth century

B.C., when this city was an actual Aramaean

possession. This is evident from Shalmaneser

III’s Annals for his third year (857 BC.):

The city of Ana-Ashur-uter-asbat, which the

people of Hatti [i.e. the Syrians] called

Pitru [Pethor], which is on the Sagur river,

on the other side of the Euphrates, and the

city of Mutkinu, on this side of the

Euphrates, which Tiglath-pileser my ancestor

. . . had settled-which in the reign of

Ashur-rabi, king of Assyria, the king of the

land of Arumu had seized by force--those

cities I restored to their (former) estate.

(A.R.A.B. i, § 603; for the date of this

conquest see p. 142.)

(iii) Aram-Zobah and the Struggle with David

[20]

By about 1100 B.C.. the Aramaean tribes had

not only expanded in Syria, but certainly

also had penetrated, like the Israelites,

into underpopulated northern Transjordan.

Only with the rise of kingship in Israel,

however --late in the eleventh century, when

the Aramaeans were already consolidated into

various states—did unavoidable conflict

break out between the two growing

neighboring nations. The kingdom of Zobah

now rose to lead the Aramaeans in southern

Syria, and indeed Saul lists it among his

enemies (1 Sam. 14: 47; the M.T. refers

merely to ‘kings of Zobah’, while the LXX

has ‘king', in the singular, mentioning in

addition Beth-Rehob).

Early in Davids reign Aram-Zobah had reached

the peak of its power under the vigorous

Hadezer the son of Rehob (2 Sam. 8: 3), i.e.

a native of Aram-Beth Rehob, who apparently

amalgamated this kingdom with Zobah into a

Personalunion. While Aram-Beth-Rehob

was apparently located in the southern

Lebanon valley, Aram-Zobah lay in the north,

extending north-east of the Anti-Lebanon

into the Syrian desert, towards Tadmor. In

his heyday Hadadezer ruled over vast

territories, founding an of complex

political structure, comprising even

Aram-Damascus and other vassals and

satellites, such as the kingdom of (Aram-)

Maacah, in upper Gaulan, and the land of

Tob, somewhere in northern Transjordan (2

Sam. 10: 6, and cf. v. 19; 1 Chr. 19: 6-7).

In the south his sphere of influence reached

as far as Ammon, while in the north-west he

was checked by the kingdom of Hamath (2 Sam.

8: 9-10). Hadadezer’s expansion in the

north-east, up to the Euphrates and even

‘beyond the river’ (2 Sam. 8: 3; 10: 16; 1

Chr. 19: 16), might well be reflected in the

above cited inscription of Shalmaneser III

(p. 141), according to which a ‘King of

Aram’ conquered areas on both sides of the

Euphrates below Carehemish in the days of

Ashur-rabi, the Assyrian contemporary of

Hadadezer. In a similar retrospective

statement, in the Annals of Ashur-dan II,

the places conquered by the Aramaeans are in

a different area, though most likely also

north of the Upper Euphrates bend.[21] If

the Aramaean king in both these Annals was

indeed Hadadezer, his conquests along the

Euphrates must be dated between the

accession of Ashur-rabi (1012 B.C.) and

Hadadezer's wars against David, in the first

two decades of the tenth century B.C.

David’s threefold victory over Hadadezer and

his allies sealed the fate of this first

Aramaean empire in Syria and brought its

territories under Israelite control. The

chronological chain of events may be

reconstructed as follows; (a) Israel’s

initial war against the allied Ammonite and

Aramaean forces, who had reached even the

plain of Moab (2 Sam. 10: 6 ff.; 1 Chr. 19:6

ff.); (b) the battle of Helam (somewhere in

northern Transjordan), where the Aramaeans

employed auxiliaries from beyond the

Euphrates (2 Sam. 10:15 ff.; 1 Chr. 19:16

ff.); the final, deep penetration which took

David into central Syria, utilizing

Hadadezer’s absence in the Euphrates region,

when the auxiliary forces from Aram-Damascus

were defeated. David took as booty

especially quantities of copper (paralleled

later by the Assyrians in their successes

against Aram-Damascus) from three of

Hadadezer`s cities in Coele-Syria: Tebah

(Tibhath-Tubihi), Cun, and Berothai (2 Sam.

8: 3 ff.; 1 Chr. 18:3 ff.; and cf. Ps.

60:2).

The kingdom of Aram-Zobah thus disappears

from the historical scene, being replaced by

Aram-Damascus. The name Zobah, however,

occurs later, on bricks found at Hamath,

inscribed in Aramaic and apparently

referring to a district within the kingdom

of Hamath (cf. Hamath-Zobah in 2 Chr, 8: 3);

it especially occurs as the name of an

Assyrian province (Subatu/Subutu/Subiti) in

the late eighth and seventh centuries B.C.,

after the final fall of Aram-Damascus and

Hamath.

(iv) The Rise of Aram-Damascus

The kingdom of Aram-Damascus, which became

the foremost Aramaean state in Syria during

the ninth-eighth centuries B.C. was founded

in the latter days of Solomon by Rezon the

son of Eliadah, who removed Damascus from

under Israelite control, making it his

capital (1 Kings 11: 23 ff.), This state was

also referred to simply as ‘Damascus’ or as

‘Aram’ par exellance-- the Bible, in

Assyrian sources, and in Aramaic

inscriptions (the votive stele of Bar-Hadad

and the Zakir inscription both mention the

‘King of Aram’). Neo-Assyrian documents

refer to this kingdom by the enigmatic

appellation sha-imeri-shu (sometimes

even spelt syllabically), literally ‘(the

land) of (his) donkey(s)’ [22] though used

interchangeably with the name Damascus, it

most probably refers only to the country as

such.

The rise of Aram-Damascus was greatly

facilitated by the division of the united

kingdom of Israel, and fully exploited the

continual disputes between Judah and Israel.

The biblical source well illustrates this in

1 Kings 15: 18-19, referring to the war

between Baasha of Israel and Asa of Judah

(in the period 890-880 B.C.), when the

latter induced ‘Ben-Hadad the son of

Tab-Rimmon, the son of Hezion’ to change

sides. The biblical passage first informs us

of the dynastic line at Damascus (the Hezion

there may possibly be the above mentioned

Rezon, founder of the kingdom),[23] and

then of the changes in allies--the first

alliance is between Tab-Rimmon and Asa’s

father, Abijah of Judah; the next between

Ben-Hadad and Baasha of Israel; and finally

there is the proposed military pact between

Ben-Hadad and Judah, which was followed by

an Aramaean campaign wresting eastern

Galilee from Israel (v. 20).[24]

Aramaean pressure on northern Israel

increased even to the point of threatening

its very existence. The Upper Transjordan

region, to Ramoth-Gilead in the south, a

buffer-zone with a mixed Israelite-Aramaean

population (cf. 1 Chr. 2: 23; 7: 14),

changed hands every so often, as is evident

during the Omride dynasty in Israel.

Ben-Hadad (II, apparently), in attempting to

attack the Israelite capital at Samaria with

the auxiliary forces of thirty-two vassal

kings, was repulsed by King Ahab; shortly

afterwards he was again defeated at Aphek in

southern Gaulan (1 Kings 20). The subsequent

treaty returned those towns in Transjordan

conquered by Ben-Hadad I, and granted

Israelite merchants preferential rights in

Damascus, like those enjoyed previously by

the Aramaeans at Samaria

(1 Kings 20: 34). Ben-Hadad II, forced to

reconstitute his army and his kingdom, also

in reaction to a new Assyrian threat,

reduced his vassal states to mere provinces

(cf. 1 Kings 20: 24-25), and thereby

consolidated his empire.[25]

To meet the menace posed by Shalmaneser Ill

of Assyria, a league of twelve western

kings, including Irhuleni, King of Hamath,

and Ahab of Israel, was initiated and led

apparently by Ben-Hadad II (probably the

Adad-idri of the Assyrian sources).

The first clash occurred in 853 B.C. at

Qarqar in the land of Hamath.

The allies had under Adad-idri 1,200

chariots, 1,200 riding horses, and 20,000

infantry; under Irhuleni 700 chariots, 700

riding horses, and 10,000 infantry; and

under Ahab 2,000(!) chariots and 10,000

infantry. The enormous force under Ahab may

have included auxiliaries from Jehoshaphat

of Judah (cf. 1 Kings 22: 4, and also 2

Kings 3: 7), and from vassals such as Ammon

and Moab. The only other independent

Aramaean king participating in this battle

was Baasha, ‘son of Rehob’, from the land or

mountain of Amana (KUR A-ma-na-a-a---

cannot be Ammon, written in Assyrian sources

always as Bit-, but once Ba-an-

Am-ma-na-a-a, with geminated m,

as in the Bible), probably referring to the

Anti-Lebanon, biblical Mount Amana (Song.

1:4) As this Baasha may have combined under

his rule two separate entities, Aram-Beth-Rehob

(see p. 141, on Hadadezer son of Rehob) and

the mountainous region to the east, only a

single contingent of infantry is ascribed to

him (analogous to the combined forces of

Beth-Rehob and Zobah in the war against

David, mentioned in 2 Sam. 10: 6).[26]

A war between Ahab and Ben-Hadad at Ramoth-Gilead

(as in 1 Kings 22) is unlikely so short a

time after the battle of Qarqar, for this

western alliance of kings seems to have

remained intact, meeting Shalmaneser III

again in 840, 848, and 845 B,C. [27] Only

Hazael, who overthrew the Ben-Hadad dynasty,

reversed Aramaean policy towards Israel,

clashing with Ahab’s son Joram in 842 B.C.

at Ramoth-Gilead (2 Kings 8: 28 f.; the

alleged encounter here in the days of Ahab

probably reflects this later event). This

disintegration of the western alliance

finally enabled Shalmaneser to defeat

Aram-Damascus in 841 and 838 B.C., in the

first instance destroying the plantations

and orchards surrounding Damascus, and then

proceeding through the Hauran and Galilee to

Mount Ba’al-rasi (‘Ba'al of the Summit,

possibly Mount Carmel).

Hazael, however, was able to consolidate his

realm after the Assyrian pressure ebbed,

bringing Aram-Damascus to the peak of its

power, and later giving his name to the

synonymous appellation Beth-Hazael, after

the dynastic founder (Amos 1: 4; and in

Tiglath-pileser III’s inscriptions, for

which see below). In the south Hazael first

seized Transjordan down to the Arnon brook

(2 Kings 10; 32 f.), then raided into

western Israel, bringing it to its knees (2

Kings 13: 7, 22), and finally reached the

borders of Judah, which was forced to pay a

heavy tribute (2 Kings 12: 17 f.).

These developments are well reflected in the

Elisha cycle (which assigns the prophet a

part in the overthrow of the Ben-Hadad

dynasty; 2 Kings 5-7; 8: 7-15; and cf. also

the condemnation of Aramaean atrocities

against Israelite Gilead, in Amos 1: 3-5).

The

Aramaeans were able to retain their position

into the reign of Hazael’s son, Ben-Hadad

III (2 Kings 13; 3; and cf. 2 Chr. 24: 23

f.), who formed an extensive coalition,

encompassing even southern Anatolia, against

Zakir, King of Hamath and La'ash.

The tide turned, however, when Adad-nirari

III renewed campaigns against the Aramaeans

in Syria in 805-802 B.C. primarily against

Damascus and its king, ‘Mari' (the Aramaic

word for ‘Lord', probably referring to Ben-Hadad

III). On a stele recently found at Tell el-Rimah,

Adad-nirari III records the heavy tribute

extracted from Aram-Damascus (silver,

copper, iron, and fine garments), in

connection with an expedition to the

Mediterranean in 802 B.C., or one against

the district of Mansuate (in the Lebanon

valley) in 796 B.C. (both campaigns are

listed in the Assyrian Eponym Chronicle).

Among the tributaries here is, for the first

time in an Assyrian source, 'Iu’asu the

Samaritan, i.e. King Joash of Israel; [28]

his appellation as ‘the Samaritan’ may imply

(as with the later Menahem `the Samaritan’)

that his kingdom was

initially limited through earlier Aramaean

conquests to the district

of Samaria alone. Because of Damascus’ weak

position Joash was able to deal Ben-Hadad a

threefold blow and recover many cities

lost to the Aramaeans by his father Jehoahaz

(2 Kings 13: 19, 25).

Jeroboam II pursued his father Joash’s

aggressive policy towards

the Aramaeans, who were further weakened by

Shalmaneser IV

during his campaign to Damascus in 773 B.C.

Jeroboam succeeded

not only in freeing all Transjordan but even

in imposing Israelite

domination over Damascus (2 Kings 14: 25,

28). Aram-Damascus

had one final flicker of glory under its

last king, Rezin, who is

mentioned as a vassal of Tiglath-pileser III

in about 738 B.C. He

rebelled and invaded Transjordan, annexing

it as far south as

Ramoth-Gilead, and even raided Elath (2

Kings 16; 6). Forcing

Pekah of Israel to join him, he pressed upon

Jotham, King of

Judah,

and his son Ahaz, who appealed to Assyria

for deliverance

(2 Kings 15: 37; 16: 5, 7 ff.; Isa. 7: 1

ff).

Tiglath-pileser lll crushed Aram-Damascus

once and for all in his campaigns of 733 and

732 B.C., boasting that he destroyed 591

cities in sixteen districts and exiled

numerous inhabitants (cf. 2 Kings 16; 9),

where Rezin’s execution is noted). ‘The

widespread land of Beth-Hazael in its

entirety from Mount Lebanon as far as the

town of Ramoth-Gilead, which is on the

borderland of the land of Beth-Omri I

restored to the territory of Assyria. I

appointed over them officials of mine as

governors.’[29]

Aram-Damascus was then broken up into

Assyrian provinces: Damascus in the centre;

Hauran, Qarnini (biblical Karnaim), and

Gilead in the south; Mansuate in the west;

and Subatu in the north (see p. 143). An

unsuccessful rebellion broke out in Damascus

in 720 B.C., in conjunction with similar

events in Samaria, Arpad, and perhaps also

Sam’al, which were all quelled by Sargon.

The destruction of the erstwhile flourishing

kingdom of Damascus left a deep mark in the

oracles of doom uttered by Amos (1: 3-5),

Isaiah (17; 1-3), and Jeremiah (49:

23-27).[30]

(v) The Legacy

a. Political organization

The combined evidence of the Aramaic,

Assyrian, and biblical sources provides an

insight into the structure and political

groupings of the various Aramaean states, at

least in Syria. We can thus follow the

continual rivalries and constantly changing

alliances among them, as well as the

Aramaization evolving in the tenth-eighth

centuries B.C. in the neo-Hittite states,

such as Ya’dy-Sam’al (capital: modern

Zinjirli), Til Barsip (later capital of Bit-Adini)

in the north, and Hamath in middle

Syria.[31] Though the vast Aramaean

expansion in Hither Asia failed to lead to

pan-Aramaean political or cultural unity,

confederations of considerable

extent, but of changing leadership, did

periodically rise in Syria:

Aram-Zobah--- ca. 1000 B.C.;

Aram-Damascus---ninth century B.C.; Arpad

(mentioned in 2 Kings 18: 34; 19: 13, et

al.; capital; modern Tell Refad, some 30

km. north of Aleppo)---mid-eighth century

B.C. The stature of Arpad about this time is

attested in the Aramaic treaty inscriptions

from Sefire (south of Aleppo),[32] which

contain such indicative terms as ‘all Aram’

and 'Upper and Lower Aram’.

Such pliant and internally loose

confederations, however, readily

disintegrated under outside pressure.

b. Language

Of the few traces of Aramaean culture left

among the peoples with whom the Aramaeans

intermingled, Aramaic and its script are the

outstanding ones. There appear Aramaic

inscriptions, chiefly in Syria (and

interestingly also in the Jordan valley), as

early as the ninth-eighth centuries B.C;.[33]

Though adopting the Phoenician alphabet,

Aramaic developed its own specific form, and

occasionally was even written in other

scripts (in cuneiform on a tablet from Uruk,

and in demotic on Egyptian papyri).

‘Imperial’

Aramaic became the lingua franca of

the Persian period, and (eventually spread

over an area from Asia Minor and the

Caucasus to India, Afghanistan, northern

Arabia, and Egypt.

Aramaic clearly played an important role in

the realm of administration and diplomacy

already in the Babylonian, and even the

Assyrian, empire. There are several

indications of this (apart from the Aramaic

inscriptions and many loan-words from

Mesopotamia), such as the mention of an

‘Aramaic letter’ (egirtu armitu,

employing an Aramaic loan-word) by an

Assyrian official in the second half of the

ninth century B.C.; of ‘Aramaic documents’ (nibzi

armaya, using the Aramaic term nbz) in

the late eighth century B.C., frequent

references to `Aramaean scribes’

alongside Assyrian; and depictions of them

in pairs on reliefs and in wall-paintings

from the time of Tiglath-pileser III onwards

(the one writing on a tablet in cuneiform,

and the other on papyrus or

leather---certainly in Aramaic).[34] The

Bible notes the diplomatic use of Aramaic in

Palestine as well (cf. 2 Kings 18: 26 ff.

--- c. 700 B.C.), as is confirmed by a

letter found at Saqqara in Egypt (600 B.C.;

most likely sent from Philistia).

The spread of Aramaic, facilitated by its

simple script, was furthered by large scale

population movements: mass deportations of

Aramaeans, and their resettlement within the

Assyrian empire;[35] their service within

the Assyrian army and administration; and

their widespread mercantile activities. The

latter, along the international trade

routes, and Aramaean settlements at the

major caravan stations, coupled with their

inherent wanderlust, place them to the fore

of Middle Eastern commerce from the ninth

century B.C. onwards.

c. Religion

Aramaean religious influence on other

peoples is obscure, for the Aramaeans

themselves were readily influenced by their

adopted surroundings. Thus many foreign

deities (e.g. the Canaanite Ba’al-Shemayin,

Reshef, and Melqart; and the Mesopotamian

Shamash, Marduk, Nergal, and Sin) appear in

Aramaean inscriptions. The principal

Aramaean deity in Syria was the ancient

west-Semitic storm-god Hadad, worshipped,

e.g., at Damascus (cf. the dynastic name

Bar/Ben-Hadad). At Sam’al, the Aramaeans

worshipped Hadad alongside the dynastic gods

Rakib-El, Ba’al Hamman, and Ba’al Semed, as

well as Ba`al Harran, whose cultic centre

was at Harran. Other deities venerated among

the Aramaeans are revealed by the theophoric

elements in personal names, especially at

Elephantine and other colonies in Egypt;

these include such gods as Nabu, Bethel, and

the female deities Malkat-Shemayin and Banit,

who also had shrines in the Aramaean colony

at Syene.[36] Traces of Aramaean religion in

the Hellenistic period appear at such places

as Baalbek and Hierapolis, the main cult

centre of Atargatis, the female deity whose

name combines 'atar (as in Aramaic

names, e.g. at Seflre (Atarsamak) and

Elephantine) and 'atta (Anat). Among

the Israelites the influence of Aramaean

worship is evident in Ahaz’s introduction of

the Damascus cult at Jerusalem,

as

reflected in the Damascus-style altar (2

Kings 16: 10-13; and cf. 2 Chr. 28: 23).

The ‘sacrifice’ of Ahaz’s son (2 Kings 16:

3; and cf. 2 Chr. 28: 3) may be further

evidence for such influence, since this was

a cult practice among the Aramaeans exiled

to

Samaria from Sepharvaim; the Adrammelech of

this cult (2 Kings 17; 31) was almost

certainly the god Adad-melek, who, at the

Aramaean centre of Gozan, was also the

subject of such rites. [37]

Note also the worship of Hadad-Rimmon, the

local deity of Damascus, in the Megiddo

plain (Zech. 12: 11; cf. 2 Kings 5: 18). On

the other hand, Aramaean susceptibility to

lsraelite religious influence is evident in

the episode of Naaman, army commander of the

King of Aram-Damascus (2 Kings 5: 15-17). ln

a later period Aramaean religion made itself

felt among the Jewish colonists at

Elephantine, and, in turn, Jewish influence

is seen in such names as Shabbetai in the

Aramaean community at nearby Syene.

d. culture

Excavations at such centers as Tell Halaf

(Gozan, in the ninth century B.C., during

the reign of King Kapara),[38] Arslan Tash

(Hadatha) and Tell Ahmar (Til Barsip),

Zinjirli (Sam’al), Tell Refad (Arpad),

Hamath, have revealed the Aramaean cultural

achievement, especially in architecture,

sculpture, and other arts.[39] The Aramaeans

were always strongly influenced by the

specific local environment, in Mesopotamia

by the remnants of the Mitanni culture and

by the Assyrians, and in Syria by the

neo-Hittites and Phoenicians. Though such

evidence is difficult to interpret, the

zenith of Aramaean material culture seems to

have been reached in the tenth-eighth

centuries B.C.

The Aramaeans though seen by their enemies

as fugitives, treacherous, a roving

people`[40] and in spite of their lack of an

original, creative culture---certainly hold

their special place in history as a major

catalyst of civilization in the ancient Near

East. |