|

Dr. Jeff Rose

is an archaeologist and

anthropologist specializing in the

prehistory of the Arabian Peninsula and

surrounding regions. His areas of interest

touch upon a variety of subjects including

modern human origins, Neolithization, stone

tool technology, archaeogenetics, rock art,

geoarchaeology, submerged landscapes, Near

Eastern mythology, and the transmission of

oral traditions. He holds a B.A. in Classics

from the University of Richmond, an M.A. in

Archaeology from Boston University, and an

M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Southern

Methodist University.

|

The Aramean Kingdoms of Sam'al

During the second millenium B.C.E.the Hittites, a group of people

who spoke an Indo-European language, established an empire, Hattusa,

centered in north-central Anatolia (the Asian part of modern-day

Turkey). The empire reached its height in the 14th century B.C.E.,

but by the 12th century B.C.E. had broken up into a number of

independent Neo-Hittite city-states. By the beginning of the first

millenium B.C.E. a number of the Neo-Hittites states were being

overrun by “roaming” Aramean tribes who spoke a Semitic language,

Aramaic.

Accounts from the ninth century B.C.E., mainly Neo-Assyrian, depict

the Aramean tribes either wrestling with Luwian/Hittite kings for

their territories, or joining together with them in an effort to

stave off the Assyrian conquest. In the famous battle of Qarqar in

853 B.C.E. a coalition of Neo-Hittite and Aramean kings, which also

included king Ahab of Israel, formed an anti-Assyrian alliance

against Shalmaneser III.

It was about this same time, the mid-ninth century, that the Aramean

kings began to produce their own written records, though few would

survive. Unlike Assyrian and Babylonian cuneiform, the Arameans

wrote with an alphabet used mainly on papyrus or animal skin. Such

perishable materials can survive only in the most arid climates such

as that of Egypt or Judean desert, but not in the rainier regions

where the Aramean kingdoms emerged. Therefore little of Aramaic

literature from before the Persian period has survived except for

those inscribed on stone in funerary and architectural monuments.

The monumental inscriptions of these early Aramean kings make up the

bulk of Iron Age Aramaic Literature.

The Semitic language of the Aramean inscriptions, as with their

other cultural traditions displays a blend of Syrian, Anatolian and

Phoenician elements. The Hittite influence was particularly evident

in traditions of royal administration, monumental scultpture and

literature. The gods seem to have remained Semitic, at least in

name, though Hittite counterparts were often recognized for Semitic

deities. Several of the early Aramean inscriptions are reminiscent

of Hittite courtly literature known from the Late Bronze Age. The

Hittites had two writing systems: a form of Akkadian Cuneiform

adapted for their Indo-European Hittite, and an indigenous

hieroglyphic system called Luwian.

The Arameans borrowed much from the Neo-Hittites especially in terms

of royal and administrative practice. But their Canaanite/

Phoenician alphabet they borrowed from a near-by Semitic culture.

Some of the earliest Aramean monumental inscriptions, such as those

from Sam'al are written in Phoenician with many Aramaic elements.

Although they use the Phoenician alphabet instead of Luwian

Hieroglyphics their habit of sculpting the letters in bas relief so

that they stand out from the stone, imitates the Luwian

inscriptions. Most other Aramean inscriptions of the period are

scratched directly into the stone.

A number of interrelated inscriptions have survived from the Aramean

kingdom of Sam'al, modern Zinjirli. These inscriptions enable us to

trace the general outline of its dynastic history and as well as the

development of its hybrid Phoenician / Aramaic dialect called

Sam'alian.

The literary structure of the Sam'alian monumental inscriptions

follows older Syrian and Anatolian traditions. The elements of the

form, whether memorial or dedicatory, are dictated by the usual

preoccupations of ancient princes and generally bear some of the

following features.

1. The first priority is to assert their legitimacy of claim to the

throne, of which heredity is the usual basis. They may also want to

emphasize their worthiness occupying the throne vis-a-vis their

predecessors. This often involves not merely being on par with

ancestors but quite surpassing them in any of their featured

achievements. It is also crucial to be specially favored by the

gods, all the more in cases where dynastic lineage is questionable.

2. Two important tests of their royal quality will be to secure the

safety and order of the kingdom first by vanquishing foreign enemies

all around and, then by pacifying or dispatching rival claimants and

other internal enemies to the throne.

3. Then follows a description of the golden days of their rule,

their own greatness and wealth as well as the well being of their

subjects. They may claim to have established measures of social

justice, economic prosperity or other benefits to the subjects. Of

course, it may have been propaganda, but could have ramifications

for the very real threat of rival claimants. In such patrimonial

systems the subjects, whether well fed or disgruntled could

influence the outcome of palace conspiracies and succession

disputes.

4. Another type of achievement often mentioned is the occasion for

the inscription itself, namely building projects. Fortifications,

gates, temples and palaces all facilitate a primitive sort of

temple-palace bureaucracy by which these Iron Age kings governed.

5. The inscription will generally conclude with stern instructions

for the preservation of the inscription itself or some aspect of the

king's life and the accomplishments the inscription symbolizes. It

may instruct the reader on the proper feeding of the king in the

afterlife, as with Panamu I. Or it may specify how successors are to

uphold his policy after him, and thereby preserve the prosperity it

achieved for the subjects. One fascinating dimension of the Samalian

royal inscriptions is the way several of the same formulaic elements

remain in place while the language, rhetoric and historical

circumstances change.

|

|

Bar Rakkib and the end of Samal

|

|

|

Bar Rakkib II

|

The inscriptions of Bar Rakkib are the last in the line of Samalian

kings. One of Bar Rakkib’s most intact records, a dolerite building

inscription, was found in 1891. Unlike the other Samalian

inscriptions which are now in Berlin, the building inscription of

Bar Rakkib is housed in the Museum of Antiquities in Istanbul. It

consists of twenty lines, recounting the construction of a second

palace between 732 and 727 B.C.E.

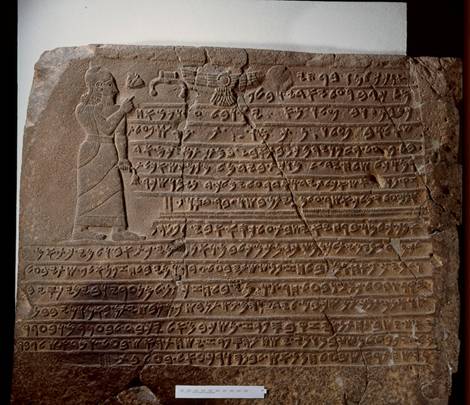

The two inscriptions pictured here were also discovered in 1891. Bar

Rakkib II is an incomplete fragment of nine lines; at the right a

bearded man holds a drinking vessel and a fan. Symbols of deity

appear at the top. In the inscription, Bar Rakkib declares his

loyalty to Tiglath Pileser, "lord of the four quarters of the

earth," and expresses the favor shown to him by the god Rakkab El.

Bar Rakkib III shows a relief of a king seated on the left, and a

servant standing on the right. On the side of the stone is a servant

standing with fan in hand. At the top is an inscription that states,

"My lord is Baal Harran.

I am Bar Rakkib, son of Panamu."

|

|

|

Bar Rakkib III, Front

|

Like the previous inscriptions the letters of the alphabet are

carved in Luwian style bas relief. The inscriptions of Bar Rakkib

are not written in the Samalian dialect but are some of the first

ancient records to use imperial Aramaic. This dialect that by the

end of the Neo-Assyrian period had become the lingua franca of the

ancient Near East is also found in the Elephantine papyri and in the

Aramaic portions of Ezra and Daniel.

As in the memorial to his father, Bar Rakkib emphasizes his own

loyalty to Tiglath Pileser III. He refers to a deity unique to Samal,

known from Kilamuwa, Rakkab El. The Assyrian king causes him to

reign, in fact, on account of his loyalty to his father and to his

god Rakkab El. Thus by circumlocution Bar Rakkib credits both the

god and his forbears as well as as the king of Assyria for his

throne.

We know nothing else of any kings of Samal after Bar Rakkib. The

Assyrian kings after Tiglath Pileser III began to replace their

policy of vassal alliance with annexation and deportation.

Eventually, Assyria, and then Babylon and Persia would bring an end

to most of the independent, often culturally distinctive Iron Age

city states. But it was the Aramaic language that became the lingua

franca of these successive empires. With its concise and efficient

alphabetic writing system adopted from the Phoenicians, it was the

Aramaic language that would bring an end to the cuneiform system

used in Mesopotamia since the dawn of civilization.

|

|

Bar Rakkib III, Side

|

|

Kilamuwa and the kings of Sam'al

|

|

|

Click the image to view an enhanced version.

|

Around the time Heinrich Schlieman made his legendary discoveries at

Troy another German archaeological team was breaking ground in

Ottoman Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). At Zinjirli, a site further

east near the border of what is now Syria they unearthed the remains

of the capital city of the Aramean kings of Yaudy, known in Assyrian

sources as Sam'al. A line of eleven Aramean kings ruled this

formerly Luwian city state from the early 900s to 713 B.C.E.

Monumental inscriptions of four of these kings have survived

beginning with the fifth king of the dynasty, Kilamuwa.

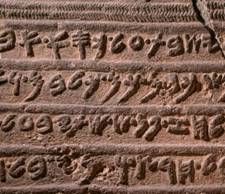

Kilamuwa's inscription was discovered in 1902 at the entrance to his

royal palace. It depicts a regal, long robed figure, presumably king

Kilamuwa himself. He holds in his hand a wilting lotus, the symbol

of deceased kings. With his other hand he points to several symbols

of deities. Beneath these is carved in bas relief the well-preserved

sixteen line Phoenician inscription. Though the language and

alphabet are Phoenician, the bas relief style of the letters

imitates the style of Luwian hieroglyphics.

|

|

|

Click the image to view an enhanced version.

|

Kilamuwa's claim to the throne seems to rest on heredity but he

mainly emphasizes the superiority of his achievements compared with

his four predecessors. First there was Gabbar, the founder of

Aramean kingship at Yaudy/Sam'al, followed by Bamah. Then came

Kilamuwa's father Hayya and his own brother, or perhaps

half-brother, Shail. We know little of the first four kings apart

from what Kilamuwa says of them. To showcase his own achievements he

says of each of his predecessors, including his father and brother,

only that they "accomplished nothing."

Fortunately Kilamuwa mentions the names of each of his predecessor's

gods. The names of these kings and their gods all seem to be

Semitic. Yet they ruled over a territory largely comprised of an

older Luwian population. The Luwians were related to the Hittites.

Most scholars believe this group is referred to in the inscription

as the mshkbm. Kilamuwa, whose name is Anatolian, mentions

the name of his mother, also apparently non-Semitic.

|

|

|

Click the image to view an enhanced version.

|

He then describes his own achievements by which he outshone his

forbears. He fended off powerful predatory kings on all sides. Only

the king of the Danunians to the west proved too much for him.

Therefore Kilamuwa "hired" the king of Assyria against this enemy.

There is no mention of Kilamuwa by name in the Assyrian records, but

Shalmaneser does claim to have gathered the kings of the Hittites

together with him in his push toward the coast. This shrewd move

resulted in economic prosperity for himself and his subjects,

particularly for the mshkbm. Kilamuwa places special emphasis on his

beneficence on behalf of these people, whom the former kings treated

like "dogs." He enriched them with livestock, gold and textiles such

as they had never seen. Furthermore, Kilamuwa seems to have achieved

some sort of leveling status for the Luwians vis-a-vis the ruling

Arameans. The wording of the inscription implies a status of

unprecedented reciprocal honour between the mshkbm and the

b'rrm. Therefore the curse that will result from defacing his

inscription is to be the undoing of this reciprocal honour. "Now if

any of my sons who shall sit in my place does harm to this

inscription, may the mshkbm not honor the b'rrm, nor

the b'rrm honour the mshkbm (Gibson 3.13 lines 13-15,

p. 35)." Kilamuwa's only reference to the gods occurs in the last

two lines. Continuing the curses on inscription vandals, he calls

upon the gods of each of his predecessors and upon Rakkab El, lord

of the dynasty, to smash the head of anyone who smashes the

inscription.

We cannot be certain of the exact nature of the social equalibrium

Kilamuwa was trying to accomplish. If the hybrid Anatolian/Aramean

influences apparent for the next century in the art, architecture

and language of Sam'al are any indication, then he must have

succeeded. After Kilamuwa there followed six more kings of Sam'al

before this Aramean kingdom practically vanishes from history.

Fortunately two of his successors also left monumental inscriptions.

Unlike the Kilamuwa inscription these are not in Phoenican. There

are either in the hybrid Phoenician/Aramaic dialect called Sam'alian

or, with the last inscriptions of Sam'al, in Mesopotamian Aramaic.

Rainey, Anson. Sacred Bridge.

Commentary by Jeffrey Rose |

|

|

|

Panamu I and the Hadad Statue

|

|

|

Click the image to view an enhanced version.

|

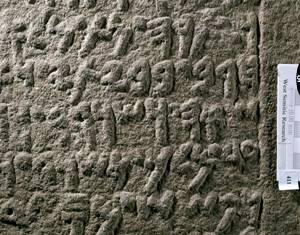

The inscription of Panamu I, the son of Qarli, did not turn up in

the excavations at Zinjirli but had already been discovered in 1890

in a village north east of the site. It is inscribed on the base of

a statue of the god Hadad. The sculpture style is of a type that has

Hittite precedents. It is a long inscription of some 34 lines, but

many of them are badly worn having been exposed to the elements.

Unlike the Kilamuwa inscription Panamu’s Hadad inscription is one of

two written in the distinctive Sam'alian dialect. Sam'alian is

mainly a mixture of Phoenican and Aramaic but also has some features

not found elswhere.

|

|

|

Click the image to view an enhanced version.

|

The inscription suggests Panamu I enjoyed a long and prosperous

rule. His reign may have spanned four decades, nearly the first half

of the 8th century. He does seem to have been in the lineage of

Kilamuwa and Qarli, but legitimizes his rule largely on the basis of

special favor the gods. He mentions five gods but the inscription

appears on a statue of Hadad. He even claims to have been in a

“covenant” with them. His special concern for the gods makes stark

contrast with the Bar Rakkib inscription, and even that of Kilamuwa.

It is however reminiscent of Zakkur and of Hittite inscriptions. By

divine will Panamu I receives the throne of his father, is made

wealthy and showers benefits on the kingdom. The land becomes

fertile; his subjects prosper in livestock. He builds and restores

temples. Panamu demonstrates a vivid concern for his own afterlife,

offering a blessing for whoever will pray that Panamu will eat with

Hadad in the hereafter. He also heaps curses on any successor that

does not care for his feeding in the afterlife.

|

|

|

Click the image to view an enhanced version.

|

Panamu I also claims to put an end to “sword and tongue,” some sort

of internal palace strife. He lays out the detailed procedure for

communal stoning in cases in which his successor would seek to

slaughter members of the royal family who might put forth rival

claims to the throne. This preoccupation for bloodless succession

and for harmony within the royal family after his death indicate

that the upheavals that followed his reign had already begun toward

the end of his life. It turns out that his worries were justified as

his successor, Bar Sur, was killed in palace plot. After Bar Sur,

the dynasty was interrupted by a usurper. Panamu II, the son of Bar

Sur, does manage to restore the dynasty using Kilamuwa’s strategy of

co-opting the Assyrian king, but this time at great cost to the

kingdom of Sam'al.

|

|

|

Panamu II, Assyrian Vassal

In the first half of the first millenium B.C.E. the Aramean city states

of eastern Anatolia and northern Syria posed a formidable challenge to

Neo-Assyrian expansionism. Yet, their various tribes never united. On

the contrary their rivalries among themselves and with the Neo-Hittite

city states could be exploited to Assyrian advantage. This appears to

have been the case with Panamu II, the 10th known king of the city state

of Sam'al. Panamu II was the grandson of Panamu I, son of Qarli who

succeeded Kilamuwa. About a century after the reign of his ancestor

Kilamuwa, the dynasty had fallen to violent intrigues from within.

Panamu II’s father Bar Sur was assassinated in a coup following the long

prosperous reign of Panamu I. In dealing with the dynastic crisis Panamu

II adopted a strategy similar to that of Kilamuwa before him, taking

refuge in Assyrian intervention. But this is a quite a different Assyria

than that of Shalmaneser III whom Kilamuwa “hired” a century before. The

change becomes particularly evident in Assyria’s Syrian and Anatolia

ambitions under Tiglath Pileser III. This is the socio-political

situation to which the Panamu II inscription bears witness.

|

|

|

Click the image to view an enhanced version.

|

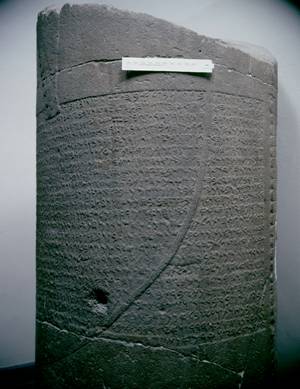

The inscription, now housed in the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, was

discovered during the German excavation at Zinjirli in 1888. It was not

Panamu II himself, who died an untimely death in battle, that

commissioned the inscription, but his son Bar Rakkib. The inscription is

both a memorial and dedication. Like the Hadad inscription of Panamu I

it is written in the Sam'alian dialect. Like the Hadad inscription,

Panamu II was inscribed around the base of a pillar-shaped statue,

perhaps of a god or king. The fringe of the figure’s robe runs

diagonally from right to left down the middle of the inscription’s 23

lines of text. All of the lines are well preserved at the beginning but

fade out gradually. Many of the lines become untranslatable at the far

left and have been variously reconstructed. The details of the dynastic

intrigue it reveals confirms that the violence and upheaval Panamu I

feared came true. In fact, Bar Rakkib seems to insert details, in a

badly preserved section, referring to a prophecy of Panamu I, predicting

bad times during the reign of a usurper. This tradition about his

grandfather’s prophetic faculties would be consistent with Panamu I’s

claim of being in a covenant with the gods. Indeed, Panamu I’s

successor, Bar Sur, was murdered by a usurper. Whether this was an

internal enemy from within the royal house or some external pretender we

do not know for certain. The usurper is not named but suggestively

referred as the “Stone of Destruction.”

|

|

|

Click the image to view an enhanced version.

|

Whether it was the usurper or Bar Sur’s son Panamu II that would have

been the successor justified by Sam'alian tradition we do not know. But

it was Panamu II that took action to assure he would be the one to live

to tell about it. The assassination of his father Bar Sur prompted

Panamu II to flee to Assyria on chariot and to “bring a gift” to their

emperor.

Compared to the Hadad inscription, there is a noticable absence of

Panamu I’s concern for the gods. Where the king usually links his claim

to the throne to his relation to the gods, Panamu II credits the

Assyrian king with killing the usurper and restoring the dynasty. All

the usual divine praise for legitimacy and then abundance is now

attributed to the Panamu II’s loyalty to Assyria. Tiglath Pileser III

expanded his kingdom northwards into Gurgum and possibly Quwe (both in

what is now south central Turkey). Whereas Panamu I had boasted of favor

from the gods, Panamu II is honored by “mighty kings,” or so his son

boasts. Panamu II does carry out some of the usual reforms, frees

captives, empties prisons, comforts women, and his subjects prosper. The

usual building projects for which a king is remembered are different for

Panamu II. As he bought legitimacy at cost of being a vassal, the cost

of tribute probably would have left little budget for fortifications or

bureaucratic hubs such as expanded temple and palace complexes. What he

does mention where one would expect the mention of building projects is

that he appointed some sort of proto-bureacratic officials, “lords of

villages and lords of chariots.” These were probably necessary to meet

his part of the deal with Assyria which would have involved taxes and

military support.

|

|

|

Click the image to view an enhanced version.

|

The rest of the commemoration praises Panamu II’s loyalty as vassal to

Tiglath Pileser III, even to personally serving Tiglath Pileser III in

battle and being killed in action on campaign in 732. This was probably

the same campaign that brought about the end of the northern kingdom of

Israel which also fell in 732. Tiglath Pileser III and all the kings and

camp wept for Panamu II. They brought his body back to Assyria and he

was buried there. Finally, the Assyrian king established his son Bar

Rakkib, the author of this inscription, on the throne of his father. Bar

Rakkib concludes by invoking the usual gods, Hadad and all the gods of

Yaudy, that is Sam'al.

Sam'al briefly prospers by the Assyrian vassaldom. Panamu II not only

restored the dynasty of his ancestors but, also with the aid of Tiglath

Pileser III, greatly expanded the kingdom of Sam'al northward into the

area wrested from Gurgum. Yet the strategy Kilamuwa called “hiring” the

Assyrian king this time proved far more costly to Sam'al’s relative

political autonomy and lingering Anatolian cultural traditions. Many of

the Neo-Hittite and Aramean citystates permanently lost their

independence under Tiglath Pileser III. It was Panamu II’s successor,

Bar Rakkib, a distinctly Aramaic name, who comissioned this inscription

for the memory of his father in the Sam'alian dialect. The language of

Bar Rakkib’s own inscriptions however, is not Sam'alian. In the

Sam'alian inscriptions up to Panamu II, the kingdom is called by its

older name, Yaudy. Yet in Bar Rakkib’s own inscriptions he calls the

kingdom Sam'al. This is the name by which it is known in the Assyrian

and Aramaic sources such as those of Tiglath Pileser III and Zakkur. The

epigraphic data of the region then suggests that after Panamu II an

early form of imperial Aramaic finally supplants the Sam'alian dialect

and along with it the unique hybrid Anatolian/Syrian culture of this

kingdom.

Commentary by Jeffrey Rose

http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/wsrp/educational_site/ancient_texts/panamu.shtml |

|