|

HAYIM TADMOR (JERUSALEM) HAYIM TADMOR (JERUSALEM)

ON THE ROLE OF ARAMAIC IN THE ASSYRIAN

EMPIRE

HAYIM

TADMOR

Contemporary research has thrown increasing

light on a highly significant facet of

culture in the Assyrian Empire: the

symbiosis of Aramaic and Akkadian[1]. A

surprising breakthrough in this respect was

the publication of the bilingual inscription,

cuneiform and alphabetic, from Tell

Fekheriye in Syria, incised on the statue of

a ruler from Gozan, which is written in

archaic style in Akkadian and Aramaic [2].

We can now state fairly confidently that

bilingualism was current on the Western

periphery of Assyria, the bulk of whose

population consisted of Arameans, at the

very least from the mid ninth century B.C.E.

onward [3].

However, it was only some 120 years later,

when the territories west of the Euphrates

were conquered that this symbiosis was

officially recognized and Aramaic became the

second language of the empire, alongside

Akkadian.[4]

1. See: A. L. Oppenheim. Letters from

Mesopotamia. Chicago 1967. pp. 42-48;.J

Muffs. Studies in the Aramaic Legal Papyri

from Elephantine, Leiden 1969. pp. 189-190;

H. Tadmor, The Aramaization of Assyria, in:

J. Nissen & J. Renger, Mesopotamien und

Seine Nachbarn (XXV. Rencontre

Assyriologique Internationale 1978). Berlin.

1982. pp. 449 -469; A. R. Millard. Iraq XLV

(1983) [XXIX Rencontre Assyriologique

Internationale. 1982). pp. 101-107; F.M.

Fales, Aramaic Epigraphs on Clay Tablets of

the New Assyrian period (Studi Semitici.

nuova serie 2). Rome. 1986. pp. 36-47 (henceforth.

Hales.Epigraphs).

2. See: A. Abu-Assaf. P Bourdreuil & A.

R. Millard. La Statue de Tell Fekherye,

Paris. 1982; J.A. Kautman. Maarav III (1982)

pp. 137-175; R. Zadok. Tell Aviv IX (1982).

pp. 117-129; J.C. Greenfield & A. Shaffer.

Iraq XLV (198.w). pp. 109- 116; idem.

Anatolian Studies XXXIII (1983), pp. 123

129; idem. RB XLII (1985). pp. 45-59; F.M.

Fales. Svria XL. (1984). pp. 233-250; idem,

Epigraphs, pp. 40-43.

3. For an early interchange between

Akkadian and Aramaic verbs ”to kill” (daku >

qatalu) in the Assyrian scribal practice of

the tenth century, see my note: Towards the

Early History of qatalu, The Jewish

Quarterly Review LXXVI (1985), pp. 51-54.

4. This may be seen as a reversal of

the practice current in the 2nd millennium

B.C.E in the lands west of the Euphrates.

Then it was a Western Akkadian that was

served as the language of literacy and

lingua franca throughout the whole area,

including Egypt. The cuneiform archives of

the royal chancelleries at el-Amarna,

Urgarit, and Hattusha document this practice.

The literary centers of Canaan (e.g. Hazor,

Aphek), where the alphabetic script was

already incipient use, yielded evidence of

extensive use of Akkadian. For cuneiform

texts from Hazor see:

B. Landsberger & H. Tadmor IEJ

XIV (1954), pp. 201-218; W.W. Hallo & H.

Tadmor,

IEJ XXVII (1977), pp. 1-11, H.

Tadmor, ibid, pp. 98-102: For those form

Aphek see:

A.F. Rainey, Tel Aviv II

(1975), pp. 125-129; III (1976), pp.

137-140; D.I. Owen

Tel Aviv VIII (1981), pp. 1-17;

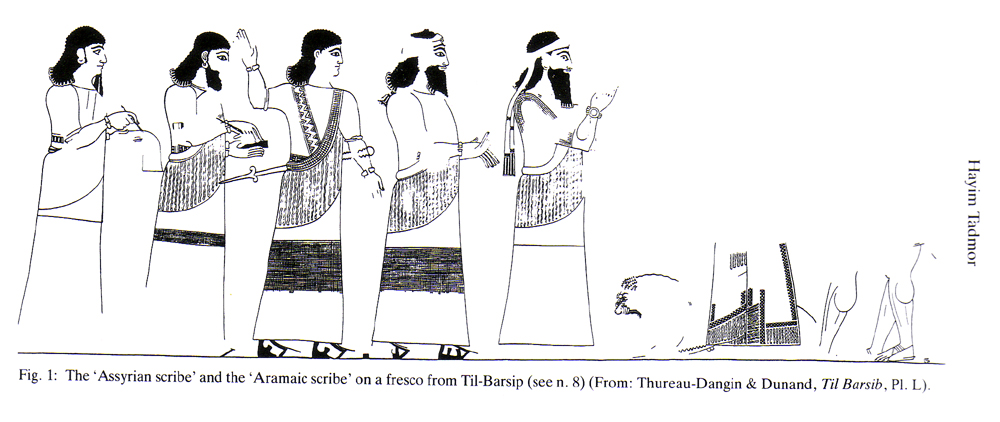

Assyrian reliefs beginning from the time of

Tiglath-pileser III [5] provide nurnerous

portrayals of a scribe writing on a tablet

or a board,[6] side by side with another

scribe writing on papyrus or a parchment

scrolI.[7] Such scribes would record the

loot taken in battle or count the number of

enemy casualties.[8]

This pictorial rendition undoubtedly

corresponds to the phrases "Assyrian scribe"

(tupsharru Ashuraya) and "Aramaic scribe"

(tupsharru Aramaya) that occur together in

the various documents, referring to

officials in the imperial service.[9] The

"Aramaic scribe" was of particular

importance in the western part of the

empire, where the royal correspondence was

conducted also, or according to some

authorities primarily, in Aramaic.[10] As

the Aramean elements in Assyria

W. Hallo, ibid., pp.. 18-24.

For the early alphabetic ostracon from

'Izbet Sartah, see M. Kochavi,

Tel Aviv IV (1977). pp. 1 13.

A, Demsky, ibid. pp. 14~27.

5. See. eg,. R.D. Barnett & M. Falkner

The scriptures of Tighlath-Pileser Ill,

London. 1962, Pls.

V-VI; G. R. Driver. Semitic Writing.

London, 1948. Pls. 23B 24C; D.J. Wisernan,

Iraq XVII

(1955), Pl. III, 2.

6. D.J. Wiseman (above. n. 5, pp. 8-13)

has argued convincingly that the rectangular

object the

scribe is holding is not a clay

tablet, but rather an ivory or a wooden

board (in fact. a hinged

diptych). covered with wax.

7. For textual evidence of writing on

papyrus (niyaru and urbanu). see CAD, N, II,

p. 201;

W. von Soden. AHw p. 1428. Writing on

parchment is attested mainly from

Neo-Babylonian documents; see CAD. M. I. p.

31 S.V. magallatu (an Aramaic loanword). In

Neo-Assyrian documents, parchment (KUSH

nayaru. CAD. N, II. p. 201) is rarely

mentioned.

8. I. Madhloorn has suggested that

the person holding a scroll was not a scribe

but an artist, whose

task was to sketch battle

scenes that would later be carved on stone

reliefs.

(Acta Antiqua Academiae

Scientiarium Hungaricaie XXII (1974). p.

385).

I believe however that

conclusive evidence against this thesis may

be furnished by a fresco

from Til Barsip, a major

Assyrian administrative center in the

western part of the Empire

(F. Thureau-Dangin-M.Dunand.Til

Barsib, Paris. 1936. Pl. pp. 54-55). It

portrays two scribes

(Fig. 1), one writing on a

tablet and the other on a sheet of papyrus.

standing behind

three courtiers who are facing

the king (only the lower part of his figure

survives, with part

of a crouching lion). Since

this fresco is concerned not with a military

campaign in a

foreign land, but with a

ceremony at the royal court, it stands to

reason that the person

holding the sheet of papyrus,

standing beside the scribe with the tablet,

is, not an artist but

likewise a scribe, recording the

royal instructions in Aramaic.

9. See the evidence collected by J.

Lewy, in Hebrew Union College Annual XXV

(1954), pp.

185-190. For the list of dignitaries.

K. 4395. in which the tupsharru Ashuraya is

followed by the

tupsharru Ar(a)maya (p. 188 rr.

74), see now MSL, Xllr p. 239 V: 5-6.

10. See: S Parpola, `Assyrian Royal

Inscriptions and Neo-Assyrian Letters`, in

F. M. Fales (ed.),

Assyrian Royal Inscriptions:

New Horizons, Rome, 1981, pp. 122-123. It is

not surprising that the

Neo-Assyrian Empire in the west

needed Aramaic as a kind of lingua franca

for its official

dealings. After all, Assyria

had inherited what had been the kingdom of

Darnascus, with its

existing administrative system;

see B. Mazar. "The Aramean empire and its

relations with Israel`,

BA XXV (1962). pp. 111-112 (now

in his "The Early Biblical Period:

Historical Studies, Jerusalem

1986, pp. 163-165).

gained ascendancy particularly as a result

of mass deportations.[11] scribes in the

capitals of the empire were obliged to

acquire proficiency in both scripts,

cuneiform and alphabetic. Indeed, there are

economic documents dating from the seventh

century written on clay tablets in Akkadian

with annotations [o…….] even summaries in

Ararnaic.[12] To my mind. such documents

were most likely written by a single scribe,

fluent in both languages.[13] The same

pertains also to the oracular queries on

certain state matters, put before the

Sun-God Shamash and the patron of extispicy.

lt is stated there that very often the

tablet of query was

accompanied by a slip of papyrus (niyaru,

urbanu) which carried the name of the

person concerned - the subject of the

query- inscribed, no doubt, in Aramaic.[14]

Through such bilingual scribes Akkadian

absorbed not only Aramaic terms in many

areas such as administration, literacy, and

even warfare,]15] but also spelling

conventions characteristic of alphabetic

script.[16] In Babylonia, during the period

of the Assyrian Empire and particularly

under the Neo-Babylonian kings, there was

even a special term, sepiru, borrowed from

Aramaic. to denote the bilingual scribe.[17]

This term was written sometimes phonetically

(se-pi-ru) and sometime ideographically: (A.

BAL, literally "one who converts,

transposes." i.e. a person who reads a text

in one language and translates it into

another) [18] A related term is targummanu .

"interpreter." already known in Old Assyrian

and Western Akkadian of the second

millennium B.C.E.; the corresponding

ideogram is EME. BAL "one who converts

speech."[19] This term apparently signifies

a person who translates oral communications,

in contrast to the sepiru, who is concerned

with writing.[20]

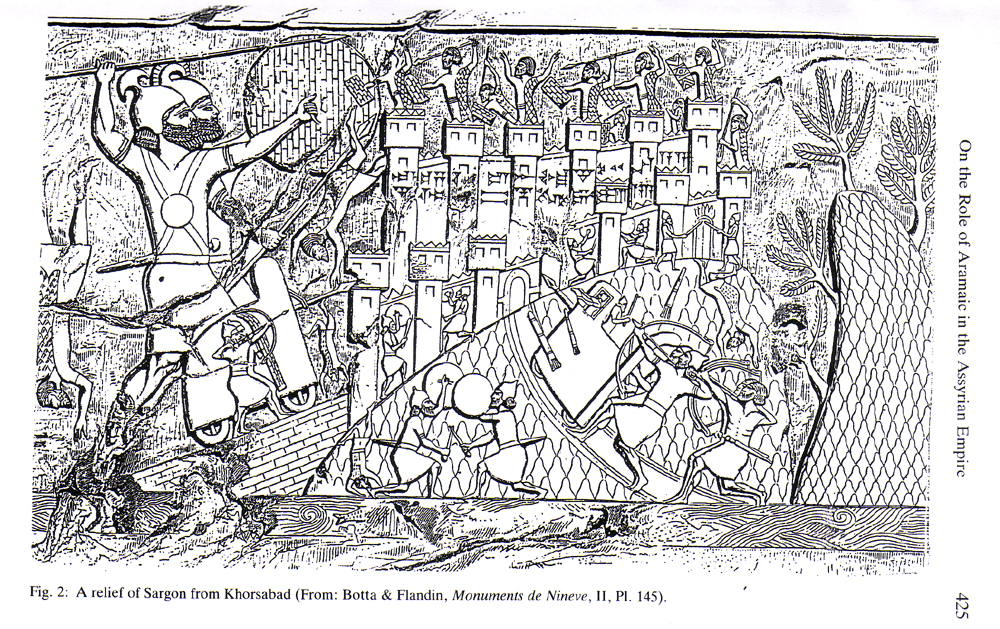

Of special significance in this connection

is the relief of Sargon II from his palace

at Khorsabad which portrays the siege of a

city in a hilly country (Fig. 2)."

11. See: B Obed,. Mass Deportations and

Deportees in the Neo-Assyrian Empire,

Wiesbaden. 1978.

12. See: S.J. Lieberrnan. BASOR 192

(1968), pp. 25-31; J. Naveh, The Development

of the

Ararnaic Scripts`, The Israel

Academy of Sciences and Humanities,

Proceedings, V/I (1970),

pp. 16-17, and now in detail,

Fales, Epigraphs.

13. See: `Ararnaization of Assyria`

(above. n 1); p. 453.

14. See. J.A. Knudtzon. Assyrische Gebete

an den Sonnengott. Leipzig, 1983, Nos 50:4.

124:4, 131 r.2.

15. See. `Ararnaization of Assyria`

(above. n. 1), pp. 454-455.

16. See: A. Poebel. Studies in Akkadian

Grammar (Assyriological Studies,

lX),(Chicago 1939. pp. 60-64.

17. Cf. J. Lewy (above, n. 9). pp. 191-199.

18. Ibid, p 196, n. 108.

19. See: I.J. Gelb ‘The Word for Dragoman

in the Ancient Near East’, Glossa II (1968)

pp. 93-104.

20. See: J. lewy (above, n. 9), pp. 196, n.

108.

21. See: P. E. Botta & E. Flandin,

Monuments de Nineve, Paris 1849, II, Pl.

145; IV, Pl. 180: 1-2 M El-Amin, Sumer IX

(1953), p. 219-225.

As the late Y. Yadin observed, an officer,

leaning out of the turret of a siege

Rnachine, holds a scroll in his hands,

apparently appealing to the besieged

inhabit-

ants to surrender (Fig. 3),[22] Yadin

suggested that this scene recalls the

biblical

description of Rab-shakeh, the royal

chiefcupbearer, who called upon the people

of Jerusalem to surrender before

Sennacherib. his master. (II Kings 18:

17-35).

According to the cuneiform epigraph

inscribed across the relief, the city be-

sieged by Sargon was "Pa(?)-za-shi, the

fortified city of Mannea."[23] Hence, the

language used by the officer. who is holding

the scroll and addressing the people

of the city, must have been Mannean. As, to

the best of our knowledge, the

Manneans did not possess any script for

their language, it stands to reason that the

scroll in the officer`s hands was inscribed

in Aramaic, like any other scroll in the

hands of scribes on Assyrian reliefs. Such

an officer might have been an "lnterpreter

of Mannean, targummanu sha Mannaya, a term

attested in a Neo-Assyrian document.[24]

Naturally. a person holding a text in

Aramaic and translating it aloud. would be

an

Assyrianized Mannean raised in Assyria as a

hostage or a deportee.

By analogy, can one surmise here that

Rab-shakeh too was reading from an

Aramaic scroll when delivering his message

to the besieged population of

Jerusalem? The appeal of the Judean nobles

to Rah-shakeh. “Please, speak to

your servants in Aramaic, for we understand

it; do not speak to us in the language

of Judah in the hearing of the people

(standing) on the wall" (ll Kings 18:26)

indicates that they expected the envoy of

the Assyrian king to address them in

Aramaic, the customary language of

diplomatic negotiations in the West. Rab-

Shake, however, had a surprise in store for

them: he harangued the people on

the ramparts of Jerusalem directly, speaking

in the vernacular.

The remarkable features of the Rab-Shake

narrative in the Bible are not only

the ability of an Assyrian envoy to deliver

an eloquent speech in the Judean

tongue, but also the very appearance of the

kings chief cupbearer as the royal

spokesman in time of war. I know of no other

case of the chief cupbearer par-

ticipating in a military delegation,

together with the Tartan (Tartanu, the

Viceroy)

and the Rab-saris (rab-sha-reshi, originally

the chief eunuch. later the commander in

chief).[25] In addition. at that period both

these courtiers outranked Rab-shakeh.

22. The Art of Warfare in Biblical Lands

JerusaIern~Ramat-Gan, 1963, , pp. 320 and

425.

23. See: C.B.F. Walker, ‘The Epigraphs` in

P.Albenda, The Palace of Sargon , King of

Assyria,

Paris, 1986, p. 112.

24. See: C.H.W Johns, Assyrian Deeds and

Documents,, ll, Carnbridge, 1901, No. 865:

6-8.;

25. It is regrettable that in the past many

scholars failed to identify properly the

titles ‘Rab-Shakeh`

and ‘Rab-saris` in ll Kings I8, both

Akkadian Ioanwords. A common error was that

the title written ideographically LU GALSAG

stands for ‘Rab~shakeh’. Examples of this

misconception

may still be found in the standard

collections of Near Eastern texts in

translation. Nowadays

Why then. of the three members of the

Assyrian delegation was the chiefcup

bearer chosen to conduct the negotiations

with King Hezekiahs representatives.

As a possible explanation of this choice, I

would suggest that Rab-shakeh, a [….]

alone of the Assyrian entourage, was fluent

in Judean and capable of delivering a

convincing propaganda speech in that

language. It is inconceivable that the

cupbearer of Sennacherib, who was certainly

not an expert in Semitics.

have acquired this fluency. if he were not a

Westerner in origin: an Israelite,

Moabite or Ammonite.[27] Highly-placed

officials at the Assyrian court, v[…]

names betray an origin west of the

Euphrates. are mentioned in numerous

monuments

from the eighth century onward.[28] In a

late Babylonian tradition. Ahikar

the hero of an Aramaic narrative, was ummanu

(i.e. the counselor and scribe of

King Esarhaddon,[29] and Nehemiah, another

Westerner, attained the position

"the kings cupbearer" in the court of

Artaxerxes l (Neh. 1:11). Such ap[…]

ments were surely no exception in the

history of royal courts. Indeed, they were

typical of Assyria. the only one among the

empires of the ancient Near East

which the language of the conquered.

forcefully acculturated, ultimately

vailed over the language of their imperial

masters.*

there can be no doubt that this title

was pronounced rab-sha-reshi, whereas the

usual ideographical

writing for the chief cupbearer

(rab-sha-qe-e), was LU GAL BI.LUL. More in

my discussion about

these two titles in C.L. Meyers and M.

O’Connor (eds.), Eassays in Honor of David

Noel […]

man. Philadelphia. 1983. pp. 279-295.

26. Cf. my comments in the Hebrew

Encyclopaedia Biblica , vol. VII, col. 324,

and a rnore recent […]

Cohen, Israel Oriental Studies IX

(1979), pp. 32-47.

27. As suggested to me by my colleague.

Prof. J. Naveh. `I`he rnain document in

Moabite is st[…]

Mesha monument. For Ammonite see now

K. P. Jackson, The Ammonite Language of the

[….]

Age (Harvard Semitic Studies, XXVII).

Cambridge. Mass., 1983.

28. See; Oded (above. n. ll), pp. 105-107.

29 See: J.J A. van Dijk, in Uruk

Vorläufiger Bericht XVIII, Berlin, 1962, pp.

44-45; J. C. Greenfield

in: Hommages a A. Dupont-Sommer.

Paris. 1971, pp. 50-51.

· The same topic is treated in a

paper which appears now in Hebrew (Eretz

Israel XX [1989][….]

249-252). The present English version has

been modified and revised. It is a privilege

to publish

it in the Anniversary Volume

for H.I.H. Takahito Mikasa. historian of the

Ancient Near East

and patron of scholarship.

|