One of the strangest, but not unexpected, battles of words and

ideologies is over the claims made about the Muslim perception of

Jihad and Jihadism and their impact on public speech. Although

there are various clashes on this level, it is appropriate here to

introduce the essence of this ideological confrontation.

In the three Wars of Ideas from 1945 to 2006, the heart of the

Western engagement in the conflict was the understanding of two

issues: what Jihad was historically and what Jihadism is in modern

times. These are two different but related phenomena.

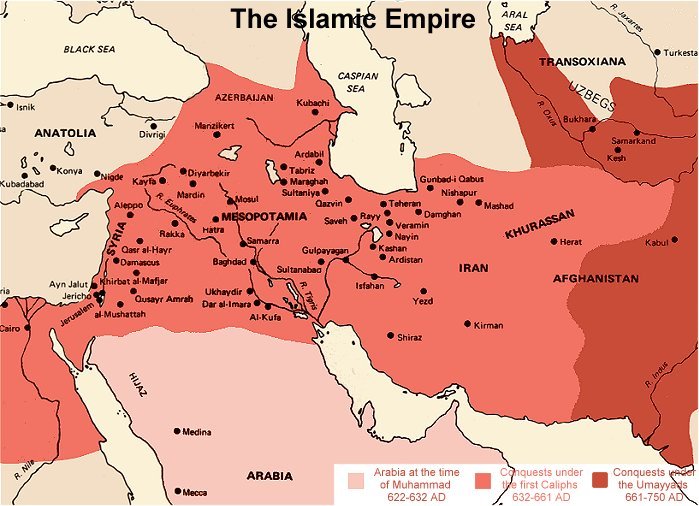

Jihad, like a number of other historical developments throughout

the world, was a religiously-based geopolitical and military

campaign that affected large parts of the world for many

centuries. It involved initial theological teachings and

injunctions, followed by 14 centuries of interpretations by

adherents, caliphs, sultans and their armies, courts, and

thinkers. The historical reality of Jihad has been intertwined

with the evolution of the Islamic state since the seventh century.

It is emphatically not

a modern, recent, and narrow creation by a small militant faction.

It has to be

seen in its historical context.

But on the other hand, this giant doctrine, which motivated armies

and feelings for centuries, also inspired contemporary movements

that shaped their ideology based on their

interpretation of the

historical Jihad. In other words, today's Jihadists are an

ideological movement with several organizations and regimes who

claim that they define the sole interpretation of what Jihad was

in history and that they are the ones to resume it and apply it in

the present and future. It is equivalent to the possibility that

some Christians today might claim that they were reviving the

Crusades in the present. This would be only a "claim" of course,

because the majority of Christians, either convinced believers or

those with a sociological Christian bent, have gone beyond the

Christianity of the time of the Crusades.

Today's

Jihadists make the assertion that there is a direct, generic, and

organic relation between the Jihads in which they and their

ancestors have engaged from the seventh century to the

twenty-first. But historical Jihad is one thing, and the Jihad of

today's Salafists and Khumeinists is something else.

Today's

Jihadists make the assertion that there is a direct, generic, and

organic relation between the Jihads in which they and their

ancestors have engaged from the seventh century to the

twenty-first. But historical Jihad is one thing, and the Jihad of

today's Salafists and Khumeinists is something else.

As with all historical events, literary, analytical, and

documentary efforts to interpret and represent past episodes

frequently influence the psychology, imagination, and passions of

modern-day humanity. Textbooks across the world detail battles,

discoveries, and speeches that are the benchmarks of the formation

of the national or

civilizational identities of peoples.

But even if the events in some nations' eyes are proud episodes,

they are often considered disasters by other nations. The Native

Americans obviously do not celebrate the Spanish conquests; the

British Empire

is a matter of pride to the English but not to the colonized

peoples; and Napoleon's "liberations" are not fondly remembered by

those who were conquered.

And this is the perception of Jihad among classroom pupils in the

Arab and Muslim world: it is a matter of historical pride. For

example, in the books from which I was tested for my history

classes, a famous general of the Arab Muslim conquest, Khalid Ibn

al Walid, is treated as a hero because he conquered

Syria,

Palestine,

and

Lebanon's

shores. But to Aramaics, Syrians, and Jews, he was a conqueror. He

was what Cortez was to the Mexican Indians – an invader.

In the same textbooks, Tariq bin Ziad, the general who led the

Muslim armies into

Spain,

is presented as the hero of heroes; but in the eyes of the

Iberians, he was

a conqueror, and in the modern lexicon, he would be described as a

colonial occupier.

So, historical

perception

is really in the eyes of the beholder.

This is about Western guilt here.

While the

latter culture has largely demythologized its own conquerors and

ideologies, once described as heroic – Napoleon, Gordon of

Khartoum, "Manifest Destiny," etc – it has accepted docilely ideas

like the "spread of Islam," the benevolence of Arab occupation,

etc. Westerners are schooled to repudiate the errors of the past

in their own culture, but to overlook those of other cultures

today. This is where the Jihadi propaganda campaign deliberately

harps on "Muslim resentment of the Crusades," in order to play

upon this "guilt complex."

Historical Jihad doesn't escape this harsh rule of history. Those

who felt their ancestors' deeds were right – including military

invasions and their violent consequences – see Jihad as a good

thing. And those who felt their ancestors were conquered and

victimized see it as a disaster. This is the drama of the invading

Arabs on the one hand and the conquered Persians, Assyro-Chaldeans,

Arameans, Copts, Nubians, and Berbers on the other; of conquering

Ottomans and conquered Armenians, Greeks, and Slavs.

It should be noted that many of the conquered had been conquerors

earlier, such as the Greeks, Persians, Assyrians, and Egyptians.

World history is made up of such reversals. But the emotional

perception of the past should stop at contemporary reality.

Feelings and passions about the tragedies of the past cannot be

erased and should not be forgotten, but they have to give way in

the end to international law and doctrines of human rights.

Many Christians today may believe that the Crusades were warranted

at the time, but that cannot become a basis for military action

under today's international consensus. The religious legitimacy of

the Crusades or the Spanish Conquista no longer exists. Even the

theological ground upon which many European Christians settled

North America,

although studied as an historical phenomenon, is irrelevant after

the Constitution. And despite the fact that many Jews invoke

religious Zionism as a basis for the re-creation of modern-day

Israel,

and that this is a deep conviction of many evangelical Christians,

international law doesn't allow it as a component for the

recognition of the state of

Israel.

In essence, twenty-first-century world society does not and cannot

function as an extension of past centuries' theologies and

philosophies. There is a full freedom of religion and thought for

individuals and communities to believe in their faith's tenets

regarding questions of land, nations, war, and peace. But these

beliefs have standing under international law only insofar as they

correspond to, and fall within, the world consensus on peace and

coexistence.

From this perspective, the question of contemporary Muslims and

Jihad cannot be an exception. Today's Muslim individuals and

communities may have their feelings, passions, and readings of

past historical Jihads. Some may attach a religious value to them.

But even if in the past jihad was a tool of the state and

considered a legitimate form of warfare led by the caliphs (in the

same way the Crusades and biblical wars were legitimate in the

eyes of their peoples), under international law today there are no

legitimate Jihads. The theological authority of Charlemagne and

Caliph Haroun Al Rashid, and of Louis XIV and Suleiman the

Magnificent may have been mainstream during their times, but not

anymore. Hence neither French president Nicholas Sarkozy nor

Iranian president Ahmedinijad can invoke religion in his defense

or when discussing international policies.

Thus the Muslims' relationship with this old and historical Jihad

is in the domain of past events and emotions; however, it can be

reinterpreted to fit the form of modern society in such a way that

it does not violate international law. Jihad as a personal

"spiritual" dimension can exist, but only as different, separate,

and distant from the historical Jihad.

The new proposition advanced by scholars in the West that a

nonviolent, inner, and personal Jihad is the "real one" can be

tested only in the wake of a cultural, widely accepted principle

that the historical, theologically endorsed Jihad warfare is over,

and not just suspended or hidden. Short of this fundamental reform

in Jihad perception, similar to the modern repudiation of the

Crusades and biblical wars by Christians and Jews, any current

political affiliation with the ancient Jihad would be in

contradiction with contemporary international law. Hence the

argument that the Muslims have "sensitivities" regarding the issue

of historical Jihad, which therefore cannot be criticized or

maligned, is at odds with the current structure of international

relations and laws.

As long as a world consensus exists on the nonreligious nature of

international relations, the political and legal dimensions of the

historical Jihad cannot be played out in the international or

public policy affairs of modern society.

One cannot argue, for example, that jihad is the equivalent of

self-defense in the modern international system. Self-defense

doesn't relate to any theological concept. But if self-defense in

Islamic religious law covers oral insults to Islamic values, then

Muslim governments or a future caliph could declare wars of "self-defense"

based on mere statements made by individuals and groups (thus, the

Danish cartoons would have justified Jihad against Denmark in the

name of "self-defense").

Similarly, if to some Christian sects self-defense could be linked

to an "end-time" theology, or if future religious groups through

self-defense could be a response to a divine order to reshape

humanity by force, these interpretations could lead to a collapse

of the planetary order.

In sum, the basis of twenty-first-century peace is to abandon the

racial, religious, and cultural legitimization of wars.

International society, with its various nations and cultures,

including the Muslim ones, has agreed on this since 1945, at least

in principle.

Dr

Walid Phares is a senior fellow with the Foundation for the

Defense of Democracies, a professor of comparative politics and

the author of

The War of Ideas