|

(2018)

Did ”Suroyo”

and ”Suraya” in Neo-Aramaic derive from

”Ashurayu/Ashuraya” in Akkadian cuneiform?

In my previeous article named

”The

terms “Suraya” &”Suroyo” in spoken Neo-Aramaic dialects”(2015);

I proved how far back in history followers of the pan-Assyrianist

ideology have claimed that the term ”Suroyo/Suroye”

(singular/plural in Central Neo-Aramaic of Tur Abdin)

spelled and pronounced ”Suraya/Suraye”

(singular/plural) in North(eastern) Neo-Aramaic

Sureth, has been claimed to have been originally

spelled and pronounced ”Asuraye” with an initial

A.

The conclusion was that it was amongst pan-Assyrianist

”elite” circles and propaganda only to be traced back to

Mirza Masrouf’s article ”Malkuta d-Aturaye yan d-Asuraye”

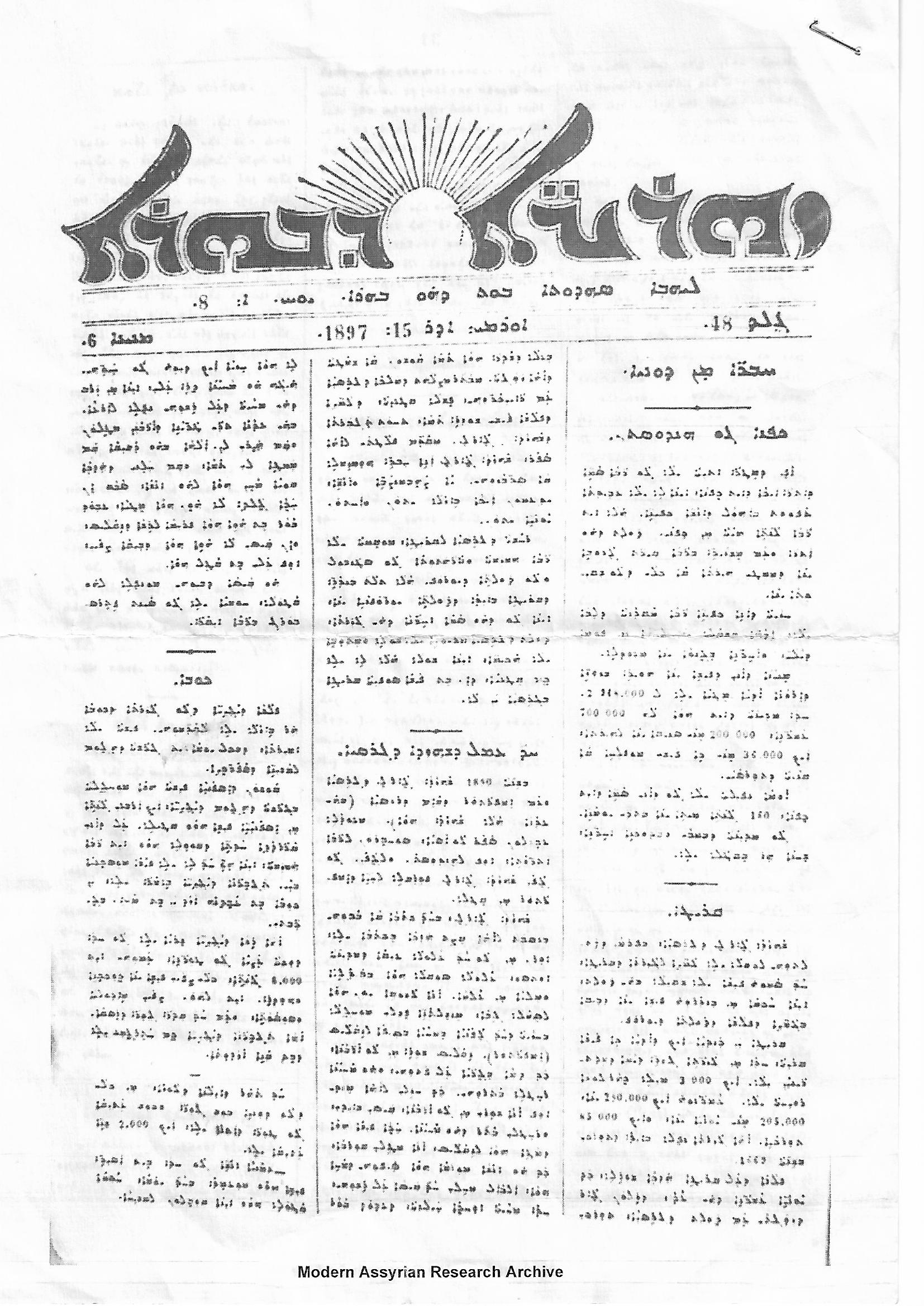

(published in the Urmia based magazine ”Zahrire d-Bahra”.

The article was from 1897 written in North(eastern)

Neo-Aramaic vernacular Sureth Swadaya by the

speakers of this form of Neo-Aramaic. It cannot be found

in the earliest written material in Sureth from

the late 1500s up to 1897 (Masroufs’s time period).

Where the term Suraye was always spelled ”Suraye”

and not as ”Asuraye” without the supposed

”original” initial A, that is traditionally as

ܣܘܪ̈ܝܐ

and

not as

ܐܣܘܪ̈ܝܐ.

Zahrire d-Bahra magazine picture from 1897.

Mirza Masroufs article “Malkuta d-Aturaye yan d-Asuraye”

the oldest pan-assyrianist

source for the name Suraye spelled as Asuraye 1897

Rudolph Macuch’s ”Gechichte der-Spät und

neusyrischen literatur”

”Rudolf Macuch (1919-1993) was a Slovakian Orientalist.

He studied at Bratislava before moving to Iran to gain

firsthand experience of his interests. He eventually

moved on to Oxford and Berlin, where he taught. He is

best known for his extensive and groundbreaking work on

the Mandaic Aramaic language.”

Back to the main topic of this article

In order to propagate the idea that the term Suraye

was evolved or originally spelled as ”Asuraye”

from the endonym (self-identification) of the

ancient Assyrians namely as ”Ashurayu/Ashuraye”

in their outdead Akkadian language; Some assyrianists in

Sweden decided to contact a finish Assyriologist Simo

Parpola at Helsinki University.

But I will illustrate to the readers that Simo Parpolas

method fails in this

matter, and why. It is in his latest paper known as

“Assyrian

identity in ancient times and today”

( in Journal of the Assyrian Academic Studies 18:2

(2004), p. 18.)

where he draws a parallel analogy between the Assyrian

identity and citizenship and that of Roman identity of

both the Western and Eastern Roman empire of Byzantium

and the Roman identity and citizenship of being Romans

(greek: Rhomaioi). Let us scrutinize his

methodology and footnote regarding his “evolutional

claim”.

Parpola wrote: “The self-designations of modern

Syriacs and Assyrians, Sūryōyō [17] and

Sūrāyā,[18] are both derived from the ancient Assyrian [Akkadian]

word for "Assyrian",

Aššūrāyu, as can be easily established from a closer

look at the relevant words…..”

and

“3.1 The Neo Assyrian Origin of Syriac and Modern

Assyrian Sūryōyō/ Sūrāyā

The word Aššūrāyu is an adjective derived from the

geographical and divine name Aššur with the

gentilic suffix -āyu. The name was originally pronounced

[Aššūr], with a palato-alveolar

fricative but owing to a sound shift, its pronunciation

was turned to [AӨӨūr] in the early second

millenniu BC.[19] The common Aramaic word for Assyria,

ĀӨūr, reflects this pronunciation and

in all probability dates back to the twelfth century BC,

when the Aramean tribes first came into

contact with the Assyrians. Towards the end of the

second millennium, another sound shift took

place in Assyrian, turning the pronunciation of the name

into [Assūr] (Parpola 1974; Fales

1986, 61-66). Since unstressed vowels were often dropped

in Neo-Assyrian at the beginning of

words (Hameen-Anttila 2000, 37), this name form later

also had a shorter variant, Sūr, attested in

alphabetic writings of personal names containing the

element Aššur in late seventh century BC

Aramaic documents from Assyria .[20] The word Assūrāyu,

"Assyrian", thus also had a variant

Sūrāyu in late Assyrian times.”

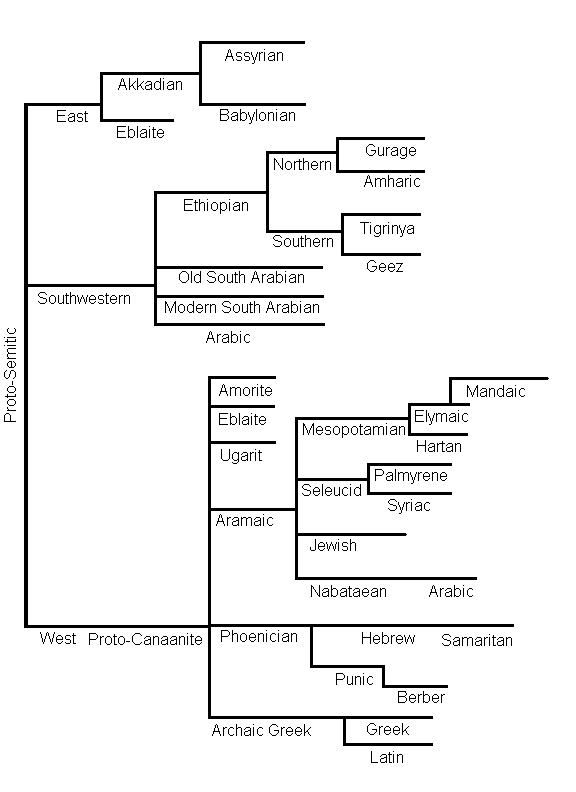

Neo-Assyrian refers in assyriology to the Neo-Assyrian

imperial period 900s to 600s BC the last development

phase of the Assyrian dialect of Akkadian. In contrast

to its precursors Middle Assyrian and Old Assyrian.

Parpola’s footnotes 17 to 20 has the following info:

[17]. "A Syrian, Palestinian" (Payne Smith 1903, 371 s.v.).

Note that in classical Syriac, the

toponym Sūrīya also covered Mesopotamia and Assyria (=

Sūrīya barōytō,"Farther Syria", ibid.

370).

[18]. "This is the ordinary name by which the E. Syrians

call themselves, though they also apply it to

the W. Syrians or Jacobites" (Maclean 1901, 223).

[19]. The shift [š] - [ө] was an internal Assyrian

phonetic development leading to the merger of /š/

and /ө/, as evidenced by the use of a single set of

cuneiform graphemes (ŠA, SI, ŠU) for both /š/

and /ө/ in Old Assyrian (Hecker 1968, § 40a). That the

merger resulted in /ө/ not /š/ is proved by

variant spellings like OA I-ri-tim (= [Iriөim]) for

normal I-ri-SI-im (genitive of Irišum, Hecker

1968, § 40i), or MA ti-ru (=[Өīru]) for * šīru "flesh"

and ut-ra-a-aq for *ušrâq "he will thresh"

(Mayer 1971, § 17), where /ө/ (< */š/) is rendered with

graphemes normally used for writing the

alveolar stop /t/ (and its fricative variant [ө]).

[20]. srslmh = Aššūr-šallim-ahi, KAI 234:2; srsrd =

Aššūr-(a) šarēd, Y-41 236 r. 4; srgrnr =

Aššūr-gārű'anēre, AECT 58:4 (taking srsrd for a spelling

of

*Šarru-(a)šarēd is not possible, since the name in

question is not attested in Neo Assyrian). The

dropping of the initial vowel in [Assūr] → [Sūr] has a

perfect parallel in the Neo-Assyrian variants

of the divine name Ištar ([Iššār] → [Šār], see Zadok

1984, 4; the short form [Šār] is already attested

‘in the inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III, see PNA

2/1569 s.v. Issār-dūrī 4).”

Here are Parpola’s fallacies according to Johny Messo’s

(Leiden University 2011) “

“THE ORIGIN OF THE TERMS ‘SYRIA(N)’ & SŪRYOYO ONCE AGAIN”

:

“First, Parpola did not give a single example of the

alleged Neo-Assyrian self-designation

*Sūrāyā,

for the simple reason that such a name did not exist in

pre-Christian Assyrian [27]

or Aramaic. He obviously relied too much on the already

mentioned artificial form

(’)sūroyo that was constructed in the late 19th century.

Secondly, what he actually did with the mere three

examples he provided was elevate a defective

spelling of the divine name Assūr (< Aššūr), which he

found in Aramaic texts from the seventh

century B.C., to a rule. After normalizing it, he

extended this exceptional form Sūr both to the

selfascription of the Assyrians by claiming the variant

*Sūrāyu and to their country/empire by

suggesting the shortened but again unattested form *Sūr.

That they were imported into Aramaic

after the Assyrians adopted this language is thereby

also disproven. It is in these two aspects

that [Robert] Rollinger followed Parpola[28] and hence

should be corrected. And so must be

Rollinger’s view that the Luwian term Sura/i for

geographical “Assyria” was taken over by the

Arameans or another Aramaic-speaking population in

northern Syria who purportedly spread it

further east[29]”

and he further explains:

“Next an evaluation was given of two influential

hypotheses concerning the root of the Aramaic

name Sūryoyo. The adherents of the first theory claim

that it has developed from Othūroyo, but

there is no proof for such an evolution in the history

of the Aramaic language. The second

suggestion was made by Parpola who attempted to revive

and confirm this theory. He asserted

that the ancient Assyrians designated themselves in

Assyrian, and later also in Aramaic after they

had adopted this language, as *Asūrāyā which evolved

into *Sūrāyā. It was shown, however, that

such an Assyrian and Aramaic autonym did not exist in

antiquity. Parpola’s etymological

explanation, therefore, is unconvincing and even

untenable. Personally, I believe the ethnonym

Sūryoyo can best be explained and understood against the

backdrop of the growing Hellenization

of the Aramaic-speaking populations in Edessa and its

surroundings. The Arameans were

initially capable of withstanding this process until the

third quarter of the fourth century A.D.

But since approximately the final decade of the fourth,

certainly around the early fifth century

A.D., the Christian Arameans invented the term Sūryoyo.

Constructed upon the toponym Sūrīa,

which is clearly Greek in form and which had existed at

least since the second century A.D. in

Edessan Aramaic, Sūryoyo may be conceived of as the

Aramaicized version of the Greek Súrios.

It seems very likely to me that this coinage or

neologism may have been accomplished at the

‘School of Edessa’, somewhere between 390 and 430 A.D.;

instinctively, I am inclined to date it

even more precisely between 400 and 420. It seems quite

certain that the eventual autonym

Sūryoyo did exist shortly before the Aramean church

split up into a Western and Eastern branch

from the mid-fifth century onward.

Since the members of the Greco-Aramaic translation

movement at Edessa were Greek-oriented

and became increasingly philhellenic, it offered a

suitable setting for the acceptation of the

Greco-Aramaic term. After its entrance into Aramaic,

there was a transition period until the late

fifth century during which the two autonyms, the old and

the new one, were used side by side.

The two main vehicles that were responsible for the wide

spread of the name Sūryoyo in various

other Aramaic vernaculars, some of which are still in

existence in evolved stages, were the

church as the new Hellenizing force and the Edessan

Aramaic dialect which the Aramaic church

had adopted as its spoken, literary and liturgical

language.

Interestingly, the fifth century A.D. shows a transition

period during which the Aramaic names

for ‘Syrian; Syriac’ (

ܣܘܪܝܝܐ)

and ‘Aramean; Aramaic’ (ܐܪܡܝܐ)

were used alongside each other.

Sūryoyo, the Aramaicized name of the Greek term Súrios,

eventually came to be used as a

self-designation by the Christian Arameans at the

expense of the originally Aramaic autonym

Armāyā, which at a later date developed into Oromoyo (Ārāmāyā)

in WestSyriac. In any case,

until well into the fourteenth century, and even up to

the modern era, both East- and West-Syrian

scholars from time to time expressly continued to refer

to their people and language as

ܐܪܡܝܐ,

to

be

translated as “Aramean” and “Aramaic” respectively.”

For more details read Johny Messos entire paper on the

topic

“The

Origin of the terms Syria(n) and Suryoyo” (2011)

In his latest book “Arameans and the making of

Assyrians” Johny Messo wrote that the difference

between “Suryoyo/Suryaya” and “Suroyo/Suraya”

is due to haplology. That means that the

extra letter “yud” is dropped in central

Neo-Aramaic of Tur ‘Abdin and (North)eastern

Neo-Aramaic (Sureth). In the same way the

term Tayoye and Taye, where Tayoye

has the same meaning as Araboye, both meaning

Arabs in Aramaic. While the form in central

neo-Aramaic (Surayt/Suryoyo Turoyo) namely

Taye can refer to Muslims regardless of

ethnic background the same goes for the usage of

the form Suroye/Suraye. The term was/is

almost synonymous to Christian because of the

demographic environment in a “we and them

scenario”. Where “we” are Christians and “the

others” are Muslims. But we know better today that

the form Suroye/Suraye means “Syrian/Syriac

Christians” rather than Christians regardless of

ethnic background. The term Mshihoye/Mshi(k)haye

and Kristyone/Kristyane means Christians in

Aramaic. Where the second form is due to a

Hellenistic influence from the Greek word “Kristanoi”

from the book of Acts of the Apostles in the New

Testament.

The only assyriologists I know of who believe that the

“modern Assyrians” are the direct descendants of the

ancient Assyrians are Simo Parpola and John MacGinnis

But the majority of assyrioloigists such as Hayim Tadmor,

Albert Kirk Grayson, Allan R Millard, and Ran Zadok

don’t believe it.

J. Pecirkova declared that Parpola’s ” conclusions are

too far reaching given the state of Assyrian sources

which are limited and very often hard to interpret”

T.Kwasman, J Cooper and F. Fales have also criticized

him, and K. Ross from the Department of Philosophy at

the Los Angeles Valley College as well. On other issues

linking Christian Trinitarianism and Jewish Mysticism

Kabbalah, Parpola even believes that Greek philosophy

and Biblical monotheism and the Christian religion to be

a religion of the ancient Assyrians So he believes that

pre-Christian Assyrian religion lies at the heart of the

teachings of Christianity and Judaism. And he was

criticized for this by E. Frahm. For much more details

see Johny Messo’s

“The Arameans and the making of ‘Assyrians’” at

www.johnymesso.com

Av: David Dag |