|

Do you hear what I hear? Christians in Holy Land revive the language

of Jesus

Students in town of Galilee learn Aramaic at school thanks to this

man's dedication to preserving it

By Derek Stoffel,

CBC News Posted: Dec 24, 2017 9:00 AM ET Last Updated: Dec 24, 2017

In the hills of the Galilee, the lush region in the Holy Land where

it's said that Jesus Christ grew up, residents of the town of Jish

are preparing to celebrate Christmas Mass in the language Jesus

spoke.

A handful of people from Jish are at the centre of an effort to

revive the Aramaic language — centuries after it all but disappeared

from the Middle East.

"It moves me very much when I hear Aramaic," said kindergarten

teacher Neveen Elias. "When I pray in Aramaic, I am feel I am so

near Jesus."

St. Maroun Church in Jish holds services in both Aramaic and Arabic.

(Derek Stoffel/CBC)

Maronite Christians in Jish celebrate part of their liturgies in

Aramaic during services at St. Maroun Church, which takes its name

from the fifth-century monk who founded the Maronite movement, which

is still active in the Middle East, mainly in Lebanon and Syria.

Jish, which sits just a few kilometres south of Israel's border with

Lebanon, is a mixed town where 60 per cent of residents are

Christian. The rest are Muslim.

'We still pray in it'

In the hills of the Galilee, the lush region in the Holy Land where

it's said that Jesus Christ grew up, residents of the town of Jish

are preparing to celebrate Christmas Mass in the language Jesus

spoke.

A handful of people from Jish are at the centre of an effort to

revive the Aramaic language — centuries after it all but disappeared

from the Middle East.

"It moves me very much when I hear Aramaic," said kindergarten

teacher Neveen Elias. "When I pray in Aramaic, I am feel I am so

near Jesus."

St. Maroun Church in Jish holds services in both Aramaic and Arabic.

(Derek Stoffel/CBC)

Maronite Christians in Jish celebrate part of their liturgies in

Aramaic during services at St. Maroun Church, which takes its name

from the fifth-century monk who founded the Maronite movement, which

is still active in the Middle East, mainly in Lebanon and Syria.

Jish, which sits just a few kilometres south of Israel's border with

Lebanon, is a mixed town where 60 per cent of residents are

Christian. The rest are Muslim.

'We still pray in it'

Shadi Khalloul is the man behind the revival of Aramaic. While he

remembers hearing the language in childhood, Khalloul said he didn't

really take notice of it until he was studying Bible literature at

the University of Las Vegas.

"My instructor was a Catholic instructor, and he said to us as

students, 'Don't think that Jesus spoke Spanish or English or French

or Latin … he spoke Aramaic, a language that disappeared," Khalloul

said.

"So I felt offended. I immediately raised my hand and said, 'Excuse

me, instructor, but the language still exists. We still speak it, we

still pray in it.'"

Shadi Khalloul has spent more than a decade in Jish, in northern

Israel, fighting to revive the Aramaic language. (Derek Stoffel/CBC)

Khalloul said he did not blame his instructor for thinking Aramaic

was dead, adding that it's "the fault of the people who still carry

this language" for not letting the world know Aramaic is still alive

and well.

That set Khalloul on his mission — now a decade old — to raise the

profile of Aramaic.

The school in Jish is the only place in Israel where students are

taught in Aramaic. Khalloul established the language training in the

school, where about 120 children receive several hours of language

instruction every week.

"We are also doing a Sunday school. We have Aramaic summer camps,

and we also help do recitals or concerts in Syriac Aramaic," said

Khalloul, a former Israeli army captain who founded the Israeli

Christian Aramaic Association.

About 120 students in Jish are enrolled in Aramaic language classes.

(Courtesy Shadi Khalloul)

The Maronites hail from Mount Lebanon. After world powers carved up

the Middle East in the aftermath of the First World War, Maronites

were meant to be given a homeland in modern-day Lebanon. But civil

war and sectarianism have spread adherents around the world, with

large communities of Maronites now calling Brazil, Argentina and

even Canada home.

About 11,000 Maronites live in Israel.

While Khalloul estimates that only two families in Jish — his and

his brother's — speak Aramaic as a first language, what he really

wants is to establish a town in Israel populated solely by Aramaic

speakers.

That would help, he said, deal with a dark chapter in the

community's past.

Jish is a mixed town in northern Israel with a population of about

3,000. Sixty per cent of residents are Christian, while the rest are

Muslim. (Derek Stoffel/CBC)

Many Maronites living in the Holy Land called the village of Biram

home. But they were displaced by the Israeli army during the

country's war of independence in 1948. The military ordered

residents to leave Biram, telling them they could return in two

weeks.

Unable to return home

That never happened. Many resettled in the nearby Arab town of Jish.

But Khalloul said he's optimistic the Israeli government will give

the go ahead for a new village, where they can "preserve their

language and their identity."

The more immediate focus in Jish is getting ready for Christmas.

The church is decorated with a glowing tree that towers over the

town, where streets are lit up in festive colours at night. On the

main road there's a thriving Christmas store — a rare sight in

Israel and the Palestinian territories, outside of Bethlehem.

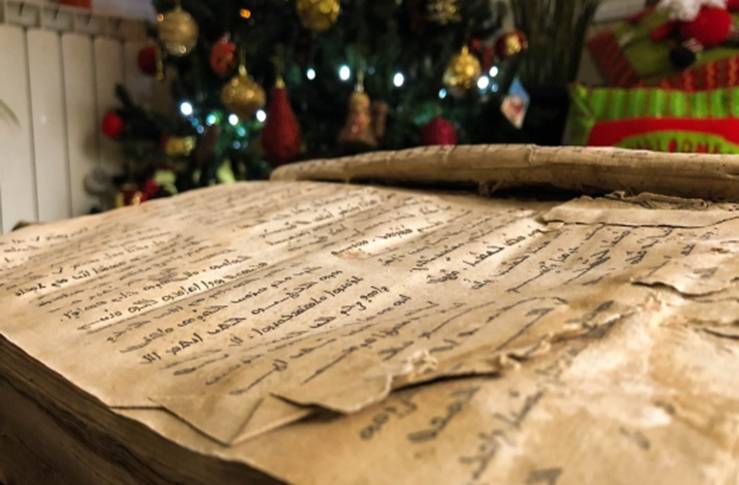

Neveen Elias reads from an Aramaic text to her children Sharbel, 8,

and Teressa, 6. (Derek Stoffel/CBC)

Neveen Elias has been practising her Aramaic, as she'll be singing

in the church choir during the Christmas mass. At home, she leads

her three children in traditional Aramaic songs.

"It's the language of Jesus, and it makes the prayers so special,"

she said.

'Language is also culture'

Shadi Khalloul and his children, wife and parents will also attend

midnight mass at St. Maroun Church this year.

He'll be looking up at the dome, where the Lord's Prayer is

inscribed in Aramaic — a reminder of the accomplishments of the

people from his town.

"Language is not only a way of communicating with others," he said.

"Language is also culture, it's identity. If I don't preserve my

language and don't respect it, how you would be able to respect me?"

http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/aramaic-language-revival-israel-stoffel-1.4460080

|